What does it look like for Australia to...

Strengthen its Indian Ocean Engagement

Published: April 2024

Executive Summary

Through its history as a modern state Australia has mostly had limited interaction with Indian Ocean countries. Arguably it has been the Pacific Ocean which Australia has looked to as the principal source of opportunities and threats.

Yet as the country with the world’s longest Indian Ocean coastline, the northeastern Indian Ocean is part of Australia’s immediate region and an area of strategic priority. This makes the increase of military buildup and competition in the Indian Ocean of great concern.

Australia has a direct interest in a stable and prosperous Indian Ocean. This means a region where people can trade freely and where countries are able to pursue their development and prosperity.

Given that stability is a key concern, Australia has an interest in supporting the conditions that enhance stability, such as the rule of law and protection of human rights. Poverty and disadvantage within the region can give rise to social tension and instability, which can spill over to the sea lines of communication in the form of piracy and irregular migration.

While there are persistent issues of disadvantage within the region, the Indian Ocean is also home to some of the world’s fastest growing economies. The rise of India as a burgeoning major power has helped shift Australia’s focus. Bangladesh can be overlooked due to the mammoth size of its neighbour, yet its own considerable population and recent strong rates of economic growth mark it as a country that cannot be ignored.

The importance of maritime routes through the Indian Ocean means that Sri Lanka and island states like Maldives are also vital. The Indian Ocean functions as a holistic strategic theatre, with instability in one sector having a flow-effect to the region as whole.

Australia’s enthusiastic adoption of the Indo-Pacific concept has helped Australian foreign policy focus on the Indian Ocean in a way that it has not done so much in the past.

However, Australia being a cultural and political outsider may work in its favour. Because it comes with significantly less baggage of history, Australia can be seen as more benign and working towards addressing the genuine problems of the region. This provides an opportunity for Australia to lead on initiatives that can help build regional habits of cooperation.

This paper sets out pathways for greater engagement in:

- Environment

- Maritime security

- Maritime response

- Search and rescue

- Maritime domain awareness

- Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing

- Port state control

- Defence diplomacy

- Diplomacy

- Education

- Diaspora linkages

- Economic security

Specific recommendations include:

- Creating an Indian Ocean Centre for Environmental Security in Perth.

- Pursuing a regional agreement to deny entry to all Indian Ocean ports to out-of-area illegal fishing vessels.

- Supporting efforts to reform the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission.

- Providing radio frequency satellite data to the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre in Madagascar and the Regional Operations Coordination Centre in the Seychelles.

- Increasing Australia’s diplomatic personnel in Indian Ocean countries.

- Placing more defence attachés in missions across the region.

- Establishing defence reserve unit relationships with small island states in the Indian Ocean.

- Expanding strategic defence dialogues in the Indian Ocean to enable officials to exchange ideas with their counterparts.

- Continuing to expand educational partnerships within the region, through the presence of Australian universities as well as scholarships and educational exchanges.

- Increasing support from Export Finance Australia and Australian Development Investments to open markets within the region.

- Expanding the current Australia-Bangladesh Trade and Investment Framework Arrangement to enable Bangladeshi products to continue to enter Australia duty-free and quota-free after Bangladesh graduates out of least-developed country status.

In line with key Australian foreign policy documents, this paper focuses on the north-eastern Indian Ocean as Australia’s primary area of interest.

While at its most expansive the Indian Ocean refers to all countries on the rim of the Indian Ocean as well as the maritime space of the ocean itself, this paper is primarily concerned with the north-eastern Indian Ocean defined to include India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka and island states and territories such as Maldives and Mauritius.

It does not focus on Southeast Asia, which is covered by other AP4D papers.

Why it Matters

The Indian Ocean is a vast and complex space home to many diverse coastal states, comprising around 35 percent of the world’s population. Given its importance as a trading route, it is also a critical national interest for many states.

Australia has the longest coastline of an Indian Ocean state. Australia has a significant exclusive economic zone (EEZ) – including from its territories of Christmas Island and Cocos Keeling Islands – and an incredibly large search and rescue area and obligations across the Indian Ocean.

Given these geographic realities, the idea of the Indian Ocean as an area of geopolitical significance to Australia is not new. The Red Sea area in particular has been a strategic driver for Australia back to the 19th Century, including during World War I, World War II and 1956 Suez crisis.

“Indian Ocean countries share common interests in the security of our region, tackling climate change, the health of our oceans, marine safety, trade, and economic development. Our region faces shared challenges, and we are working together on shared solutions.”

— Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong, 7th Indian Ocean Conference, Perth, 9 February 2024

Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review identified the northeastern Indian Ocean as part of Australia’s “immediate region” and therefore an area of strategic priority. The 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper noted that “Australia’s own connections with the world will continue to rely on our sea lines of communication”, with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade website stating that “the Indian Ocean is fundamental to maintaining open trade and energy security.”

The Indian Ocean is home to forty percent of global offshore oil production, with two-thirds of the world’s unrefined oil traversing its seas. Australia in general and the Australian Defence Force (ADF) in particular are heavily reliant on this transport. Any interruption to the sea lanes of communication across the Indian Ocean would not only have a severe economic impact on Australia but would greatly inhibit the country’s ability to defend itself.

This makes the increase of military buildup and competition in the Indian Ocean of great concern. In 2017 China constructed its first overseas military base in Djibouti, significantly increasing its Indian Ocean capabilities. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has invested heavily in port infrastructure throughout the Indian Ocean littoral. Beijing has also established the China-Indian Ocean Regional Forum on Development Cooperation, which held its second iteration in December 2023.

“We are part of this region – part of its economy, part of its environment, part of its culture, part of its people. So, we believe strongly in building the institutions of and engagement with our region, particularly in the northeast Indian Ocean.”

— Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs Tim Watts, 6th Indian Ocean Conference, 13 May 2023 Dhaka

These Chinese initiatives have troubled a number of countries, especially India which sees itself as the natural security provider in the Indian Ocean. Some see the United States as having deprioritised then reprioritised its presence in the region in recent years, adding to security uncertainty.

Australia’s enthusiastic adoption of the Indo-Pacific concept has helped Australian foreign policy focus on the Indian Ocean in a way that it has not done so much in the past. Arguably it has been the Pacific Ocean which Australia has historically looked to as the principal source of opportunities and threats. Given its long western coastline with a small population, Australia has traditionally relied on first the United Kingdom’s Royal Navy and then the US Navy for its Indian Ocean security. Australia is now required to step up both its security and diplomatic presence.

Through its history as a modern state Australia has mostly had limited interaction with Indian Ocean countries. Diplomatically, the post-colonial states in the region were members of the Non-Aligned Movement, and therefore had divergent strategic objectives to Australia during the Cold War. Diplomatic engagement with these states was mostly though the Commonwealth, with varying degrees of coordination and importance. Lack of economic complementarities meant there was little economic engagement.

There are currently limited habits of significant cooperation between countries of the region. However, Australia being a cultural and political outsider may work in its favour. Because it comes with significantly less baggage of history, Australia can be seen as more benign and working towards addressing the genuine problems of the region.

As an Indian Ocean state, Australia’s interests are intimately tied to not only the major events of the region, but to the daily lives of the region’s people. Poverty and disadvantage within various part of the region can give rise to social tension and instability, which can spill over to the sea lines of communication in the form of piracy and irregular migration. Australia has duties as a responsible global citizen to help address issues of poverty and disadvantage, contributing to Australia’s interests in a more stable and secure region.

This also comes with the recognition that the relationships born from development assistance can transform into economic opportunity. Ten of Australia’s current 15 top export markets are countries where Australia once provided foreign aid. This makes development assistance not only a moral imperative, but a key economic investment and strategic calculation.

While there are persistent issues of disadvantage within the region, the Indian Ocean is also home to some of the world’s fastest growing economies. Continued high rates of economic growth are required due to a large proportion of young people who are seeking education, skills, employment and opportunity. As a country with considerable expertise in international education, Australia can be a major partner in enhancing these opportunities – both through students studying in Australia and through the expansion of Australian educational institutions into other countries. In 2023, Deakin University signed an agreement to become the first foreign university to open a campus in India.

Running parallel to the Indian Ocean region’s development needs and economic opportunities, there needs to be awareness of the pervasive effects of climate change. The region is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change – particularly in low-lying countries like Maldives and Bangladesh. This could lead to unprecedented levels of displacement and migration, creating a major security concern for Australia. This should make climate adaptation and mitigation cooperation central to Australia’s Indian Ocean engagement.

Alongside the effects of climate change, other environmental challenges such as the depletion of fisheries have a massive impact on livelihoods in the region. Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) is not only an issue of fish-stock sustainability but is at the heart of the integrity of the international legal framework and the rules-based international order. As a country with a large EEZ, Australia is heavily invested in enhancing and enforcing mutually beneficial norms around IUU fishing in the Indian Ocean.

While the northeast Indian Ocean has been identified as a strategic priority for Australia, the Indian Ocean functions as a holistic strategic theatre. Instability in one sector has a flow-effect to the region as a whole. This is especially the case with recent disruptions to shipping in the Red Sea, which adds significant cost from diverted shipping routes, or any potential threats to oil flows from the Persian Gulf. Australia has been involved in tackling piracy off the coast of Somalia and protecting shipping through the Persian Gulf, and narcotics originating in Afghanistan are increasingly being detected in Australia.

Although Australia does not have a large footprint in Africa, vast deposits of the critical minerals that will drive the world’s technological advancements are present on the continent. In many cases Australia is a competitor to these countries in critical minerals trade or may be reliant on them depending on how these technologies and markets evolve. The strategic objective to lessen the reliance on China for green-tech materials and manufacturing may make Africa’s role in these industries more substantial and make Australia’s vision of the Indian Ocean far wider.

“The geography of Australia and India makes us stewards of the Indian Ocean region. It’s an ocean which accounts for about half the world’s container traffic and is a crucial conduit for global trade. India’s location makes it the natural leader of this region which Australia strongly supports.”

— Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Richard Marles, National Defence College New Delhi, 22 June 2022

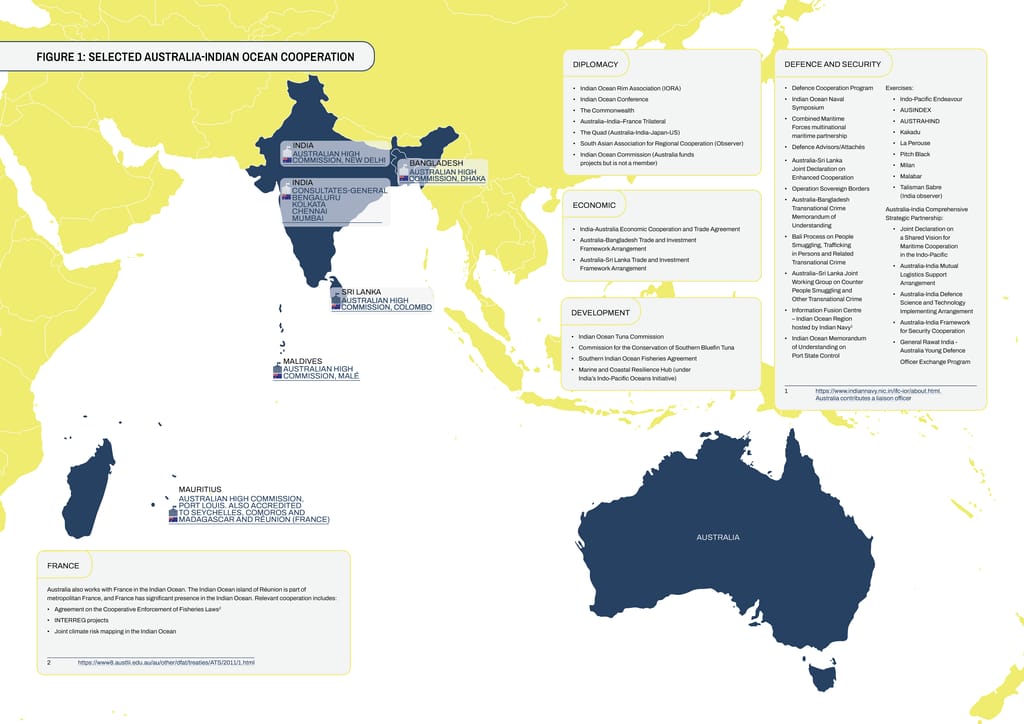

- Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA)

- Indian Ocean Conference

- The Commonwealth

- Australia–India–France Trilateral

- The Quad (Australia-India-Japan-US)

- South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (Observer)

- Indian Ocean Commission (Australia funds projects but is not a member)

- India-Australia Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement

- Australia-Bangladesh Trade and Investment Framework Arrangement

- Australia-Sri Lanka Trade and Investment

- Framework Arrangement

- Indian Ocean Tuna Commission

- Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna

- Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement

- Marine and Coastal Resilience Hub (under India’s Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative)

- Defence Cooperation Program

- Indian Ocean Naval Symposium

- Combined Maritime Forces multinational maritime partnership

- Defence Advisors/Attachés

- Australia-Sri Lanka Joint Declaration on Enhanced Cooperation

- Operation Sovereign Borders

- Australia-Bangladesh Transnational Crime Memorandum of Understanding

- Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime

- Australia–Sri Lanka Joint Working Group on Counter People Smuggling and Other Transnational Crime

- Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region hosted by Indian Navy

- Indian Ocean Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control

Exercises:

- Indo-Pacific Endeavour

- AUSINDEX

- AUSTRAHIND

- Kakadu

- La Perouse

- Pitch Black

- Milan

- Malabar

- Talisman Sabre (India observer)

Australia-India Comprehensive Strategic Partnership:

- Joint Declaration on a Shared Vision for Maritime Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific

- Australia-India Mutual Logistics Support Arrangement

- Australia-India Defence Science and Technology Implementing Arrangement

- Australia-India Framework for Security Cooperation

- General Rawat India - Australia Young Defence Officer Exchange Program

Australia also works with France in the Indian Ocean. The Indian Ocean island of Réunion is part of metropolitan France, and France has significant presence in the Indian Ocean. Relevant cooperation includes:

- Agreement on the Cooperative Enforcement of Fisheries Laws

- INTERREG projects

- Joint climate risk mapping in the Indian Ocean

Perspectives

Australia

Australia’s interests are in a stable and prosperous Indian Ocean region. This means a region where people can trade freely, mutually beneficial rules of engagement are endorsed and respected, and where countries are able to pursue their development and prosperity without interference and subjugation from outside forces.

Because of this, Australia has a direct interest in managing geopolitical competition in the region. Australia wants a strong relationship with India and wants India engaged in the region to help support a balance of power favourable to Australia’s interests.

Another key national interest is in managing people smuggling, which can be a politically incendiary issue in Australia. This is an area that takes significant resources and drives policy in the region.

Given that stability is a key concern for Australia, it also has an interest in supporting the conditions that enhance stability. Australian leaders have stated a belief that democratic states are more stable, produce greater human flourishing and are more rule-abiding by nature, yet several states in the region are weaker in their commitments to democracy.

As a traditionally Pacific-focused country, Australia has limited resources on its Indian Ocean coast. This means that the resources it does have need to be directed towards the most important issues.

Australia needs a keen understanding of what kind of Indian Ocean it wants to maintain or help build, and a focus on how power can be utilised, balanced or restrained within the region. Due to its limited resources, working with partners is central to its approach. This requires not only diplomatic nous in a region of great cultural diversity, but an understanding of the concerns and priorities of regional partners.

For Australia, understanding how the perspectives and interests of other Indian Ocean countries align with its own is critical to its cooperation engagement in the region. Many Indian Ocean states lack maritime reach to defend their own interests – which includes being able to address IUU fishing, migration, smuggling and transnational crime. As a responsible neighbour, Australia has a profound interest in helping these states reach further out into their own oceanic areas and defend their own interests.

The Defence Strategic Review recommended that Australia should continue to grow its Defence Cooperation Program in the Indian Ocean region. Australia’s hosting for the first time in 2023 of the Exercise Malabar between India, United States, Japan and Australia is a demonstration of its commitment to maintain security in the Indian Ocean region. In July 2023 several Indian navy and air force aircraft visited the Cocos Keeling Islands airfield, which is being strengthened and expanded to cater for P-8 maritime patrol aircraft. This was the latest in a pattern of reciprocal visits since Australia and India signed a Mutual Logistics Support Arrangement in 2020, and builds on other RAAF visits to Bangladesh, Maldives and Sri Lanka in 2023 as part of Indo-Pacific Endeavour. There is an active program of defence coordination with Sri Lanka on issues related to Australia’s border security.

However, apart from India, there has been a lack of official visits by Australian prime ministers to Indian Ocean countries. These visits are not simply for show, they are a strong signal of intent. Meetings at prime ministerial or presidential level send a message that these relationships are of great value and that cooperation is deemed important at the highest levels. This made the Indian Ocean Conference in February 2024 in Perth so valuable, bringing together ministers and heads of state from more than 30 countries across the Indian Ocean region.

The Indian Ocean in key policy documents

The Northeast Indian Ocean is central to Australia’s security and sea lines of communication. In addition to our engagement with India, the Government’s defence engagement in the Indian Ocean region will focus on:

The Northeast Indian Ocean is central to Australia’s security and sea lines of communication. In addition to our engagement with India, the Government’s defence engagement in the Indian Ocean region will focus on:

- regularising the ADF’s presence, including increasing deployments, training and exercises with Sri Lanka, the Maldives and Bangladesh; and

- strengthening Australia’s defence cooperation with Indian Ocean region countries through regional maritime domain awareness, growing defence industry engagement and increasing education and training cooperation.

“With India and others, we seek to strengthen regional architecture in the Indian Ocean—including the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA)— and encourage more coordinated responses to developments affecting security in the Indian Ocean region.”

“With India and others, we seek to strengthen regional architecture in the Indian Ocean—including the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA)— and encourage more coordinated responses to developments affecting security in the Indian Ocean region.”

“We will deepen joint exercises and build maritime domain awareness with India and collaborate on maritime safety and security with other Indian Ocean partners, like Sri Lanka.”“Open sea lanes link the Pacific and Indian oceans, enabling trade in goods and energy that fuels the region’s growth… Australia’s own connections with the world will continue to rely on our sea lines of communication.”

“Australia is connected to many South Asian countries by the Indian Ocean, and we will continue to support the productive and sustainable use of its resources.”

“Australia is connected to many South Asian countries by the Indian Ocean, and we will continue to support the productive and sustainable use of its resources.”

“South Asia is an important part of our vision for a peaceful, stable, and prosperous Indo-Pacific. Our engagement with its dynamic countries is growing. Almost half of the population of South Asia is aged under 24 years, and over one million people are set to enter the workforce every month until 2030. The growing effects of climate change and continued social inequality are dampening opportunities. We will support partners expand education programs and build resilient cities and infrastructure.”

India

As the region’s largest state, India plays a central role in the dynamics of the region. In recent years Australia has invested considerable resources into developing a more substantial economic, security and cultural relationship with India. This has been due to the enormous opportunities India presents as the world’s most populous country, as well as geostrategic calculations.

India sees itself as the Indian Ocean’s primary power. India is heavily reliant on the Indian Ocean for its trade – including energy imports – and the Indian Navy identifies its strategic zone as from Africa’s east coast to the Andaman Sea. This includes taking responsibility as the region’s first responder and its security provider. India’s archipelago of Andaman and Nicobar Islands are strategically located near the Malacca Strait. This gives it critical maritime domain awareness and response capabilities near one of the world’s most important shipping lanes.

China’s naval base in Djibouti and its investment in port infrastructure in Pakistan and Sri Lanka are of grave concern to India, as are the periodic incursions into Indian territory in Ladakh in India’s northwest, and Arunachal Pradesh in the northeast, the annexing of land in Bhutan, for which India has air defence responsibility, and China’s surveying activity and relationship with the new Maldives government. Although India maintains a strong strategic independence, these issues make greater cooperation with countries like Australia, the United States and Japan more attractive and necessary to New Delhi.

While India has become the world’s fifth largest economy, and has acquired significant naval capabilities, it is still a developing country. It has an increasing global reach, yet it is also still primarily concerned with enhancing the building blocks of internal prosperity. It is focused on enhancing its still substantial needs for education, employment and infrastructure.

India has seen the importance of more effective use of its port infrastructure with the SagarMala Initiative, which not only involves greater port capacity and efficient practices, but greater road and rail connectivity to ports, new industrial clusters and skills development in coastal regions. These improvements are designed to make India more attractive to foreign manufacturing investment.

Attracting a significant manufacturing capability can serve to provide widespread employment, but also negate the concentration of manufacturing in China. This is particularly important for emerging green technologies. India is keen to become a major electric vehicle manufacturer, as well as make India the global hub for production, usage and export of green hydrogen and its derivatives.

It is important to note the changing nature of Indian foreign policy. There has been a shift in India’s outlook in recent years, with a commitment to strategic autonomy evolving into a recognition that India needs to work with partners to achieve its foreign policy objectives in a more multipolar world. While some parts of Indian foreign policy – such as India-Russia relations – may cause consternation in Western capitals, New Delhi’s willingness to work with partners also presents opportunities for countries like Australia, as the revival of the Quad attests.

“As we gaze at the Indian Ocean, the challenges besetting the world are on full display there. At one extremity, we see conflict, threats to maritime traffic, piracy and terrorism. At the other, there are challenges to international law, concerns about freedom of navigation and overflights, and of safeguarding of sovereignty and of independence... In between, a range of trans-national and non-traditional threats present themselves, largely visible in a spectrum of interconnected illegal activities… All of them, separately and together, make it imperative that there be greater consultation and cooperation, among the states of the Indian Ocean.”

— Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, 7th Indian Ocean Conference, Perth, 9 February 2024

Bangladesh

Bangladesh has achieved a remarkable average rate of economic growth of 7 per cent over the past decade, and has not had a year of economic contraction over the past three decades. The country’s textile industry has been the primary driver of this growth, accounting for around 85 per cent of its exports. The textile industry currently forms the backbone of Bangladesh’s objective to graduate to a developed country by the 2040s.

Bangladesh has made significant progress in improving occupational standards within its textile industry, with safer buildings and greater environmental considerations. Bangladesh now has over 1500 companies certified by the Global Organic Textile Standard, which measures ecological and social criteria. This is making country more attractive for companies and consumers who prioritise ethical standards.

Due to its manufacturing base, Bangladesh requires reliable and consistent sources of energy and raw materials. It is also heavily reliant on open sea lines of communication, with stable rules and norms that can assist the country to export with confidence. Bangladesh’s Indo-Pacific Outlook forefronts its commitment to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Bangladesh’s unique geographical terrain, dominated by the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, means that the country is highly susceptible to the effects of climate change – in particular sea level rises, extensive flooding and increasingly powerful cyclones. This makes climate adaption and resilience national priorities alongside the country’s development objective.

The concave nature of the Bay of Bengal requires a particular capability with Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR). Bangladesh has increased its response time in the region – with significant capability in enhancement in the last 5-6 years, however the shared nature of the bay means that coordination between its resident states is vital, as is assistance from outside states when required.

Of pressing concern is that Bangladesh currently hosts the world’s largest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar. The weight that Bangladesh is carrying for the region should be recognised, one that it doesn’t have the resources itself to manage. The Rohingya refugee crisis is one that has spilled over into maritime refugee flows – an issue Australia considers a priority concern.

“The Indian Ocean holds significant importance for not only Bangladesh, but for all the countries in the region... We remain committed to playing our role for peace in the region, and expect all other countries to do the same to ensure a resilient future.”

— Prime Minister of Bangladesh Sheikh Hasina Wazed, 6th Indian Ocean Conference, Dhaka, 12 May 2023

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s location within the sea lines of communication between the northwestern Indian Ocean and the Malacca Strait has given it a role as a major service hub within the region. This has raised its geopolitical weight significantly. After the conclusion of its civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka has gained greater capacity to think about its external environment and its maritime interests.

The Sri Lankan economy has stabilised after a recent economic crisis which saw soaring prices, shortages of fuel and other essential goods and crippling international debts. Sri Lanka returned to economic growth in the second half of 2023. Widespread protests born from this crisis and a perceived lack of government accountability means that Sri Lanka also needs to strengthen its democratic institutions and the rule of law. Despite progress, the road to recovery remains long and ongoing economic and social issues are likely to affect forthcoming elections and how effectively Australia can engage.

Sri Lanka’s current challenges include maintaining its long-standing non-aligned policy in the face of increasing great power competition in the Indian Ocean – particularly balancing China’s infrastructure investments in Sri Lanka with the concerns of its neighbour India.

Alongside this, as an island state it has a keen interest in maritime safety and security, such as protecting undersea cables, responding to natural disasters, combating illegal fishing and tackling environmental issues including maritime pollution.

Sri Lanka views Australia as a friendly partner, and it has a great appreciation for and interest in issues of soft diplomacy, like education and cultural exchange. Australia is seen as a good citizen in the region in terms of development assistance. Australia’s own interests in combatting the flow of maritime asylum seekers has converged with Sri Lanka’s desire to gain greater maritime awareness and capabilities. Australia’s concerns about human rights abuses as a source of people seeking asylum has been less welcome.

“Creating a safer ocean environment by building confidence and predictability among users and enhancing ocean situational awareness will be key to maintaining peace and security in the Indian Ocean... Ensuring a peaceful and secure Indian Ocean would facilitate sustainable use of oceans for the economic and social benefit of coastal and littoral states.”

— President of Sri Lanka Ranil Wickremesinghe, 7th Indian Ocean Conference, Perth, 9 February 2024

Maldives

When considering the Indian Ocean, there is a danger in conceptualising the region through its rim, at the expense of the ocean itself. Small island states within the Indian Ocean like Maldives have a unique set of challenges that are often reliant on the cooperation of larger states.

The primary security challenge that faces a country like Maldives is climate change. Rising sea levels are an existential threat to low-lying islands and atolls. The capital, Malé, with a population of over 200,000 people, is only 2.4 metres above sea level.

Alongside the threat of climate change, the other core challenge is one of economic viability. The country has a keen interest in diversifying its economy in addition to tourism. Maldives has a highly successful tourism economy, but tourism is a vulnerable sector which is highly exposed to global economic trends and extraordinary events like the COVID-19 pandemic.

The rise of China and India have been seen as great opportunities for this diversification, although this comes with geopolitical complications. Due to its desire to be the primary security provider in the Indian Ocean region, and Maldives’ strategic location, India is heavily invested in good relations with Maldives, but New Delhi can struggle to treat its smaller neighbours with equality and respect, potentially pushing Maldives closer to China. The relationship between Maldives and India has suffered due to these geopolitical factors. It was notable that the new Maldives president elected in November 2023 made his first state visit to Beijing, rather than New Delhi.

Other Indian Ocean perspectives

As with other regions, the Indian Ocean region is comprised of states with different historical, religious, linguistic and cultural contexts. A comprehensive survey of all Indian Ocean countries’ perspectives is beyond the scope of this paper, however there are some common themes.

The Indian Ocean is also important to many extra-regional countries. Some – like France, the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan – have Indian Ocean territories or presence plus longstanding relationships. Emerging players include China, UAE, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Türkiye. This increased attention is both a cause and an effect of the importance of the Indian Ocean region and its evolving security environment.

In 2023 AP4D released a paper on What does it look like for Australia to Enhance Coordination with France in the Indo-Pacific. It made the following recommendations on working with France to multiply the effects of Australia’s efforts in the Indian Ocean:

Continue to invest in the Australia-India-France trilateral

Australia should capitalise on the political and policy momentum behind the Australia-India-France Trilateral Dialogue to drive practical cooperation in this trilateral format.

Explore opportunities to leverage French advantages in the western Indian Ocean

Australia should see France’s significant presence in the western Indian Ocean as an opportunity to boost its own influence in areas of shared interests and capabilities. With limited resources and bandwidth, Australia can make niche contributions that leverage the scale and local expertise of French and European efforts, while also bringing unique Australian advantages in capacity building.

Working with regional institutions

As much as possible, Australia should seek to channel greater cooperation and coordination with France through existing regional institutions, especially the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA). This will help boost the centrality of IORA and generate broader regional buy-in. A ustralia should also consider formalising its relationship with the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) by becoming an observer. Given Australia already engages the IOC and has funded projects with it, formal observer status would boost Australia’s status as a partner to the group.

High-potential areas for Australia-France cooperation and coordination

A ustralia should pursue closer dialogue and information sharing arrangements with French counterparts. It should continue to seek out opportunities to contribute to French and EU-led development programs through financial or in-kind support. Maritime security and safety is a key area of shared interest in the Indian Ocean. Australia should look to identify opportunities with France to support capacity building efforts in various areas, including:

- Fusion centres: Enhancing the effectiveness of the existing “fusion centres”: the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Center based in Madagascar, and the Regional Operations Coordination Center based in the Seychelles.

- Maritime safety: Australia has provided maritime safety capacity building in the Indian Ocean through the Australian Maritime Safety Agency (AMSA). Australian agencies including AMSA and the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, working with DFAT, should consider how they could make niche contributions to capacity building in this area.

- Law enforcement: Given significant transnational crime issues, especially drug trafficking and IUU fishing, the Australian Border Force and Australian Federal Police, working with DFAT, should consider how they could work with counterparts to enhance the ability to identify and prosecute transnational crime.

Disinformation is a significant concern with several documented instances in recent years. The EU has already carried out dialogue, training and capacity-building aimed at countering disinformation in this region. Australia could explore opportunities to work with France, the EU, civil society and local and international media to complement existing efforts, focussing on raising awareness of disinformation and developing skills to recognise it.

Opportunities and Barriers

Opportunities

Australia’s enthusiastic embrace of the Indo-Pacific construct has led to not only a greater awareness of the interconnectedness of the Pacific and Indian oceans but has come with a new strategic ambition. This ambition has framed Australia’s immediate region as encompassing the Pacific, Southeast Asia and the northeast Indian Ocean, continuing to Antarctica.

This is an enormous area for a middle power of limited resources to prioritise. It is an indication of both the more challenging external environment and the considerable opportunities that the region presents.

While the Pacific and the Southeast Asia have been traditional regions of focus for Australia, expanding its engagement towards the northeast Indian Ocean is essential for Australia to embrace its status as an Indian Ocean state.

The instigation for much of Australia’s burgeoning regional engagement came through the lens of environmental security and the response to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. The tsunami response was a demonstration of a whole-of-government approach to foreign policy, drawing upon the defence force, the diplomatic corps and AusAID under the direction of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. It was also a whole-of-nation effort, with businesses, community groups and individuals also volunteering their time and donating generously.

Australia’s response was primarily directed at the Indonesia’s Indian Ocean-facing provinces of Aceh and North Sumatra, as well as Sri Lanka and Maldives. But critical to these efforts was the formation of a “core group” of humanitarian responders with the United States, India, Japan. This coordination would eventually lead to the creation of the Quad and – inspired by former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe’s speech “Confluence of the Two Seas” – would shift how Australia understood its role as an Indian Ocean power regarding how it could enhance relationships and have a capacity-building impact for both itself and for partner countries.

Casting its eyes westward, Australia has primarily centred its engagement on India. As an emerging great power, building habits of trust and cooperation with India are an imperative for a world where it will play a far greater role. The abundance of opportunities presented by India’s massive population and growing market power are undeniably attractive.

Given its size and the sheer breath of opportunities it potentially provides, India has been central to Australia’s engagement in the Indian Ocean region. There has been a significant step-up in the relationship in recent years. This is certainly the case in the defence and security space, and a burgeoning major trading partner.

This increased closeness between Australia and India is not solely at the state level. Both Indians and Australians are highly active in the world and have built strong relationships of mutual interest. There are highly active networks of social and interest groups – addressing a range of issues from climate change through to gender, peace and security issues. Women’s leadership and women’s contributions are also strong between Australia and India. Alongside this, there are deepening business, academic and sporting links. These links have accelerated as Australia’s Indian diaspora has grown substantially over the past two decades.

Although recent changes to Australia’s visa system may limit the number of Indian students in Australia, education will still be an important component of the relationship, particularly with Australian universities looking to expand into India, and the increased exchange between academic institutions. India’s vast youth population in search of opportunity and Australia’s expertise in international education should continue to complement one another.

Australia’s need for specific skills will also provide opportunities with India. The pilot Mobility Arrangement for Talented Early-professionals Scheme (MATES) will allow young Indian graduates from fields related to engineering and information technology to live and work in Australia for up to two years. This is seeking to fill Australia’s skill shortages in these areas, as well as build greater opportunities for collaboration in these fields between Australia and India.

India’s desire to be an electric vehicle manufacturing power, presents complementarities with Australia’s critical minerals resources, emerging hydrogen expertise, and the Western Australian government’s investment in green steel manufacturing. With the African continent’s abundance of certain critical minerals, and the desire among Western countries to challenge China’s current dominance of green technologies, the Indian Ocean has the potential to become the future green tech theatre. Which will present both opportunities and geopolitical contestation.

Countries like Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Maldives are also entering Australia’s radar. Over the past decade Australia has increased cooperation with Sri Lanka’s navy and coast guard to help combat people smuggling, which has included Australia gifting Sri Lanka two patrol boats and a surveillance aircraft. In May 2023 Australia opened a new High Commission in Maldives, signalling not only the value of the relationship, but a desire to enhance its presence in a strategically important location.

Often overlooked due to its gigantic neighbour, Bangladesh is an emerging power in its own right as the world’s eighth largest country. With an average economic growth rate of 7 per cent over the past decade, it is following the export-oriented development path of East Asian countries, and therefore has become heavily invested in trade routes through the Indian Ocean. Australia is currently assisting with design work for two ports in Bangladesh, reflecting its importance as a manufacturing hub.

Bangladesh presents a considerable market for Australian goods and two-way trade. Bangladesh’s manufacturing industries require reliable and consistent sources of energy – something Australia can provide – and demand for staple pulses like lentils and chickpeas is high.

As a Least-Developed Country, Bangladeshi products currently enter Australia duty-free and quota-free, however Bangladesh is projected to graduate out of this status in 2026. Maintaining these conditions through expanding the current Australia-Bangladesh Trade and Investment Framework Arrangement will be critical to enhancing the trading relationship, and for Bangladesh’s continued growth. It is important to recognise that big export items like energy or agriculture are not the only 22 What does it look like for Australia to Strengthen its Indian Ocean Engagement way for bilateral relations to develop, with small company-to-company links on a range of niche goods and services having a huge impact on building a wide spread of relationships.

These market opportunities throughout the region are mostly being led by private industry. There is the potential for more support from Export Finance Australia and Australian Development Investments (ADI).

There is also the potential for the Australian government to engage with local experts to help understand local priorities, which can in turn better inform Australian engagement through more targeted development assistance and capacity building. In 2024 Australia’s High Commission in Bangladesh commissioned a multidisciplinary study from local Bangladeshi experts to look at the country’s economic security. The objective of the study is to get a picture of where and how Bangladesh’s economic and trade policies intersect with geopolitics and geo-economics, identify opportunities and vulnerabilities, and assess options that might strengthen and enhance the resilience of the Bangladesh economy. These types of programs should be expanded and extended to other countries across the region.

Despite its impressive recent growth, Australia continues to provide development assistance to Bangladesh. In recent years this has centred on care for the large Rohingya refugee population. These refugee camps are a heavy burden for Bangladesh to carry and it is the responsibility of countries like Australia to provide essential items for these people’s lives, but also pathways to resettlement. There is a lot of goodwill and a diplomatic dividend to be earned from Bangladesh in assisting with this considerable problem.

There are other unique challenges where Australia’s scientific expertise could be of assistance to Bangladesh. Within the Bay of Bengal there is a “dead zone” – an area of about 60,000 square kilometres that has depleted oxygen levels. This poses a grave threat to fishing stocks in the bay. Finding an understanding of the nature, causes, and potential remedies, is of critical importance to all states that depend on the bay.

Issues around environmental degradation and climate change are central to the non-traditional security threats that the region faces. For Australia is it essential to have an intimate understanding of what truly affects people in vulnerable areas and how they perceive these threats. Australia can then tailor its engagements accordingly. With a current lack of mechanisms or structures in the Indian Ocean region to facilitate cooperation on environmental security, there is scope for Australia to make it a key pillar of Indian Ocean engagement, as is the case with Pacific island states.

In relation to informal migration that has originated from Sri Lanka Australia has shown initiative, coordinating with the Sri Lankan navy, as well as providing vessels and an aircraft. These initiatives have the potential to advance to broad cooperation on maritime domain awareness and as well as IUU fishing.

Military coordination is about maintaining the peace, and the region has a strong commitment to providing United Nations peacekeeping forces. Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan are four of the five largest contributors to UN peacekeeping missions. India is also a locus of peacekeeper training.

What does it look like for Australia to Strengthen its Indian Ocean Engagement It was one of the first countries that sent women as peacekeepers, and it has a training institute that is now training women across the region, particular in ASEAN countries. Australian assistance would serve Australia’s interests in both India and through Southeast Asia.

Collaboration through South Asia can often be impeded by the region’s political history. Indian Ocean countries can be wary of what they perceive as overbearing or hegemonic Indian behaviour, so collaborative projects can be more appealing when they have an outside guarantor. An example of this is the India-Japan-Bangladesh connectivity program to link Northeast India to the Bay of Bengal via Bangladesh. There is the opportunity for Australia to present itself as a trusted partner and broker for engagement within South Asia.

In the coming decades as power continues to shift both to and within the Indo-Pacific, Australia will need to reconceptualise where its areas of interests lie, and this will include moving its vision westward. This will particularly be the case as China build its relationships and presence in East Africa and among the western Indian Ocean islands. While Australia’s current focus is on the northeastern Indian Ocean, the region is a single strategic theatre, and so the groundwork of building relationships throughout the whole region should be considered a priority.

India is the biggest player in the region and for bigger issues to reach positive outcomes they require India’s support. However, there is a trust deficit between other Indian Ocean states and India that needs to be overcome, and Indian-led initiatives tend to fail due to this. This presents Australia with the opportunity to be a diplomatic organiser. It can be a state that is seen as an honest broker, and which can help South Asia overcome some of the historical baggage and difficult relationships that prevent the region from solving some of its collective problems.

Senator the Hon. Penny Wong, Minister for Foreign Affairs onstage with high level dignitaries at the inaugural session of the Indian Ocean Conference (IOC) in Perth on Friday 9 February, 2024. Image courtesy of DFAT.

2024 Indian Ocean Conference

On 9-10 February 2024, Australia hosted the 7th annual Indian Ocean Conference in Perth. The Conference brought together ministers and heads of state from more than 30 countries across the Indian Ocean region. Under the theme ‘Towards a Stable and Sustainable Indian Ocean’, participants engaged in two days’ of dialogue aimed at collectively addressing maritime, climate, and strategic challenges.

It was the first time Australia hosted this important gathering. In her keynote address to the conference, Australia’s foreign minister stressed that “[Australia] will always remain a principled Indian Ocean power and a reliable Indian Ocean partner. Because this region is our region, and together, we get to determine its character.”

Barriers

Imperative to Australia’s engagement within the Indian Ocean is having a keen understanding of the relationships between countries in the region.

While certain economic and security interests have converged between Australia and India – and the relationship has gained greater intimacy – India’s historical position of non-alignment has morphed into one of multi-alignment, with New Delhi seeking as many beneficial relationships as possible. This means India is not always interested in using its diplomatic weight to align on issues that Australia and its allies feel are important. India sees itself as rising to form a major pole in a multi-polar Asia, rather than an ally of the West. This is a workable scenario to Australia, but rather than a broad like-mindedness, cooperation on an issue-by-issue basis may be how the relationship progresses.

Diaspora communities play a central role in both informal and formal ties, enhancing local knowledge of Indian Ocean countries while forming strong economic, cultural and diplomatic links. However, intra-diaspora tensions have found their way into Australia and pose a threat to the success of Australia’s immigration program, as well as potentially infecting bilateral relations. A better understanding of ethnic and religious divisions within the region is essential for Australia to make the most of its South Asia diaspora, and to address and alleviate these tensions at a local level.

The rise of Hindu nationalism and the erosion of democracy and pluralism in India creates an added layer of complexity to the relationship and makes it more difficult to advance Australia’s commitment to the rule of law and human rights goals.

Other states in the region are also experiencing rising authoritarianism and democratic backsliding. While potentially a source of internal instability, this may not necessarily hinder state-to-state level cooperation or beneficial trading relationships.

The complexity of South Asia as a whole presents another potential barrier to Australia’s engagement in the region. There are grand historical forces and deeply embedded cultural perspectives that make cooperation difficult between South Asian states. Smaller neighbours consider that India often struggles to treat them as peers, which inhibits cooperation. Alongside this, new sets of divergent interests have emerged from China’s economic gravity.

This often makes the multilateral structures within the region highly ineffective. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) is stymied without an improvement in India-Pakistan relations. The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi‑Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) – of which Australia is an observer – is primarily a trade-focused institution but may offer the region a better platform for cooperation. There are current attempts to implement a dispute-resolution mechanism to prevent inter-member difficulties from hindering the organisation.

A security related forum like the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) is having some success at finding common ground within the region, however broader multilateral forums like the India Ocean Rim Association (IORA) can struggle to achieve outcomes due to its scope and size, its consensus-drive model, and the diverse range of interests and perspectives that each country seeks to advance. Often the principle of the lowest common denominator applies.

Bilaterally, Australia’s ability to forge intimate relationships within the region are critical to its ability to be a productive and trusted partner. However, in recent years Australia’s outreach to other states aside from India has usually been in terms of dollars. Providing much needed funding on certain issues is welcome, but follow-up is also required to build the solid bonds that should be central to its engagement. There are lessons to be learned from Australia’s outreach in the Pacific, where being seen to be invested and caring is just as important as financial contributions. Relationships with Bangladesh and Maldives start from low levels and lack depth.

Although the world has mostly ended restrictions following the COVID-19 pandemic, the hit that many supply and logistics chains took during this period have on-going effects. Australia needs to recognise that the effects on supply chains persist in many ways and can still hinder the free flow of goods within the region. Although improvements have been made, labour and environmental standards within regional supply chains could also be a concern for Australian business in their attempts to diversify away from China.

The Vision in Practice

What does it look like to strengthen Australia’s Indian Ocean engagement?

Australia recognises that its interests are bound to the Indian Ocean. As an Indian Ocean state, Australia capitalises on the breadth of opportunities that the emerging region presents. This involves deeper regional integration both at an institutional level and through economic connection and enhanced people-to-people links. This includes demonstrating a commitment to the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) as the region’s primary multilateral body.

Australia understands that some of the best structures are often small and informal. Given the huge diversity of interests and perspectives within the region, large structures that seek to do too much are often ineffective. Australia will instead have the patience and long-term vision to build trust and cooperation on an issue-by-issue basis. It will coordinate to address specific issues that are important to a single regional state or common to the region more broadly.

Australia will leverage existing multilateral and minilateral activities around maritime awareness. This is an area where Australia has significant experience and major Indian Ocean states are still building their own capabilities. Australia sees it in its own interests to help advance these capabilities.

Australia enhances its strong cooperation with the Sri Lankan Navy. This cooperation should not just centre on issues related to the prevention of seeking asylum via maritime routes, but to wider issues of human trafficking, IUU fishing and general maritime awareness. Australia’s commitments to greater maritime cooperation will weaken the need for countries like Sri Lanka to seek assistance from China.

Australia will invest heavily in fishing diplomacy. At present the Pacific and Southeast Asia are the primary regions of engagement for Australia’s assistance with combating IUU fishing. Australia has worked hard with its Pacific neighbours to make the western Pacific the gold standard in combatting IUU fishing. Australia will use these structures and lessons to work with Indian Ocean countries to improve standards and outcomes in the region.

Australia supports youth opportunity and leadership as essential to building a stable and prosperous Indian Ocean region. An understanding of the region as a very young one, with its youth keen for education and economic opportunity, will be at the centre of Australia’s thinking.

A major pillar of Indian Ocean engagement will be targeted development assistance. Although the region is home to rapidly growing economies, there are still a great number of development issues that require international assistance.

Australia targets its development program intelligently on issues where Australia has significant expertise, including gender equality. It sees positive outcomes return to Australia in terms of diplomatic dividends and the economic opportunities that are born from more prosperous societies. This links with and supports the whole-of-nation approach to national defence set out in the Defence Strategic Review.

Australia has a keen understanding of the security and economic impacts of climate change in the region. Australia recognises that it has a moral responsibility to assist with mitigation, resilience-building and disaster-relief cooperation.

Australia provides humanitarian support, healthcare funding and economic recovery assistance to Bangladesh, Maldives and Sri Lanka, as well as funding for disaster preparedness. Australia leverages these connections to locate trade opportunities and improve regional cooperation.

Case Studies

IORA INDIAN OCEAN BLUE CARBON HUB

Based in Perth, Australia is host to the IORA Indian Ocean Blue Carbon Hub. Launched in September 2019 in collaboration with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), the Blue Carbon Hub aims to build knowledge and capacity in protecting and restoring blue carbon ecosystems throughout the Indian Ocean. Blue carbon allows multiple development goals to be addressed through a single policy framework that incorporates economic growth, environmental sustainability and social inclusiveness.

AUSTRALIAN HUMANITARIAN PARTNERSHIP BANGLADESH CONSORTIUM

The Australian Humanitarian Partnership is a partnership between the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and six Australian non-government organisations. It delivers high-quality targeted humanitarian programs that complement Australia’s funding to other United Nations and specialist agencies. AHP partners have been programming in Bangladesh for many years, and all have been involved in the recent upscale of operations to support Rohingya refugees and host communities in Cox’s Bazar under the program AHP Bangladesh Consortium, which is now in its fourth, multi-year response to the crisis.

INDIAN OCEAN: CURTIN UNIVERSITY AND EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY

In 2018, Charles Telfair Campus, located south-east of the Mauritian capital Port Louis, became an official campus of Curtin University. The campus delivers internationally recognised undergraduate and postgraduate degrees while researching in areas focusing on local and regional problems.

Edith Cowan University opened a campus in Sri Lanka in Colombo in 2023. Local and international students can study Australian university undergraduate programs across a variety of disciplines, including biomedical science, cyber security, design and commerce.

CENTRE FOR AUSTRALIA-INDIA RELATIONS

The Centre for Australia-India Relations is a national platform established by the Australian Government in 2023 to support and facilitate greater collaboration and engagement with India. It works across all levels of government, industry, academia and civil society to build greater understanding of the Australia-India relationship and the opportunities flowing from our burgeoning connections.

Its work focuses on promoting policy dialogue, building India business literacy and links, engaging Indian diaspora communities, and deepening cultural connections and mutual understanding.

Pathways

Case Studies

The Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) is a voluntary initiative that seeks to increase maritime co-operation among navies of the littoral states of the Indian Ocean Region by providing an open and inclusive forum for discussion of regionally relevant maritime issues. In the process, it endeavours to generate a flow of information between naval professionals that would lead to common understanding and possibly cooperative solutions on the way ahead. Australia is one of 25 member countries.

The Australian Defence Force contributes to support international efforts promoting maritime security, stability and prosperity. The Royal Australian Navy has conducted maritime security operations promoting maritime security in the Indian Ocean/Middle East region since 1990.

In Operation Manitou, the ADF has up to 16 staff embedded with the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) in Bahrain at any time. The CMF is composed of 41 member nations and five Combined Task Forces focused on countering terrorism, preventing piracy, encouraging regional cooperation and promoting a safe maritime environment. A stable security environment in the Middle East region fosters trade and commerce and ensures Australia’s safe and open access to the region.

In Operation Hydranth, the ADF contributes to support United States and United Kingdom defensive actions targeting the capabilities used in Houthi rebel attacks in the Red Sea. It comprises up to seven ADF personnel supporting the US-led coalition to degrade the threat to the safety of seafarers of all nations, navigational rights and freedoms, international trade and maritime security in the Red Sea. Australia strongly supports the international rules based order and will continue to support efforts to de-escalate tensions and restore stability in the Red Sea.

Australia Awards are scholarships administered by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. They contribute to the long-term development needs of Australia’s partner countries in line with bilateral and regional agreements. Australia Awards provide opportunities for people from developing countries, particularly those countries located in the Indo-Pacific region, to undertake full-time postgraduate study at participating Australian universities. The study and research opportunities provided develop skills and knowledge of individuals to drive change and contribute to the development outcomes of their countries.

For example, Australia has provided nearly 2000 long-term scholarships to Bangladeshis since the 1970s, with alumni occupying leadership positions in both the public and the private sectors and contribute to achieving the country’s goals in important sectors such as education, agriculture, water resources, and economic growth. Each year, about 70 Australia Awards Scholarships are provided to Bangladeshi nationals for master’s level study in Australia.

The New Colombo Plan is an Australian Government scholarship program that supports Australian undergraduates to study in the Indo-Pacific region, including Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Sri Lanka Nepal and Pakistan. The program provides scholarships for up to one year of study, grants for both short and longer-term study, internships, mentorships, practicums and research. Open to Australian undergraduates, the New Colombo Plan supports around 10,000 students each year.

The New Colombo Plan aims to be transformational, deepening Australia’s relationships in the region, both at the individual level and through expanding university, business and institutional links. A growing cohort of New Colombo Plan alumni are playing an increasingly important role in Australia’s relationships with its neighbours and becoming an influential and diverse network of Australians with direct experience in the Indo-Pacific and strong professional and personal networks across the region.

INDIA AUSTRALIA RISE ACCELLERATOR PROGRAM

The India Australia Rapid Innovation and Startup Expansion (RISE) Accelerator program is a partnership between the CSIRO and the Atal Innovation Mission (AIM), NITI Aayog – the Government of India’s flagship initiative to promote a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship in the country.

With a particular focus on environment and climate technologies, the program provides support to startups and small- to medium-sized enterprises who are working on innovative technology and are considering overseas expansion between India and Australia. The nine-month accelerator program enables Australian and Indian innovators and industry partners to tackle shared national and global challenges.

The Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) is an inter-governmental organisation formed in 1997 to foster regional economic cooperation. IORA has evolved into the peak regional group spanning the Indian Ocean. The IORA Secretariat is based in Mauritius and is headed by a fixed term Secretary-General. IORA has 23 member states and 11 dialogue partners.

IORA is the premier ministerial-level forum for the Indian Ocean region. It is tripartite in nature, bringing together representatives of government, business and academia. Its priorities are maritime safety and security; trade and investment facilitation; fisheries management; disaster risk management; academic, science and technology cooperation; and tourism and cultural exchange.

Australia is a founding IORA member and chaired the organisation between 2013 and 2015.

RESTORING CORAL REEFS IN MALDIVES

Like many countries in the region, Maldives relies on its coral reefs for sustaining local livelihoods. Its reefs are critical for coastal protection, as they reduce impacts from waves and storms which cause erosion. They are also important for economic prosperity, 58 per cent of the population is employed in the tourism sector and 98 per cent of goods exports come from reef-associated fisheries. But over the last decade, increased sea surface temperatures and the effects of climate change have resulted in major coral bleaching events.

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) has partnered with Maldives Marine Research Institute, with funding from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, to develop and train local participants in larval-based coral restoration methods to assist with reef recovery and build resilience in a changing climate.

Contributors

Thank you to those who have contributed their thoughts during the development of this paper. Views expressed cannot be attributed to any individuals or organisations involved in the process.

Alexey Muraviev

Curtin University

Anthony Bergin

Strategic Analysis Australia

Ashton Robinson

ANU Strategic and Defence Studies Centre

David Brewster

ANU National Security College

Jack Corbett

Monash University

James Bowen

Perth USAsia Centre

Jennifer Parker

Australian Naval Institute and UNSW Canberra

Lailufar Yasmin

University of Dhaka

Marc Purcell

Australian Council for International Development

Marcus Schultz

Australian Strategic Policy Institute

Michael Moignard

Former Austrade Senior Trade Commissioner

La Trobe University

Nilanthi Samaranayake

United States Institute of Peace

Niro Kandasamy

University of Sydney

Peter Layton

Griffith Asia Institute

Prakash Gopal

University of Wollongong, Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security

Prakash Mirchandani

Australian Institute of International Affairs Victoria

Richard Maude

Asia Society Policy Institute

Sohini Bose

Observer Research Foundation

Tahmina Rashid

Australia Awards Bangladesh

Thenu Herath

Australian Council for International Development

Troy Lee-Brown

University of Western Australia Defence & Security Institute

One participant withdrew from the process in protest at Australia’s support of airstrikes in Yemen in contrast to inaction and silence on the profound human rights violations occurring in Gaza.

Editors

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons license. You can reprint or republish with attribution.

You can cite this paper as: Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue, What does it look like for Australia to Strengthen its Indian Ocean Engagement (Canberra 2024): www.asiapacific4d.com

Photo on this page: ‘3 people riding on boat during sunset from Unsplash user Aman Upadhyay, used under Creative Commons.

This paper is the product of ‘Shaping a Shared Future’, a program funded by the Australian Civil-Military Centre.

Supported by: