What does it look like for Australia to...

Enhance Coordination with France in the Indo-Pacific

Published: June 2023

Executive Summary

As Australia pursues its vision for the future of the Indo-Pacific, it must forge effective partnerships to align priorities, combine capabilities and coordinate action. France – a resident Indo-Pacific power with significant resources, sophisticated statecraft and global reach – is one such partner for Australia. In the broad, Australia should welcome and seek to shape a greater French contribution to the region’s stability, security and prosperity.

The Australia-France relationship is on a positive trajectory, with greater coordination and cooperation in the Indo-Pacific a core and growing element. However, with frictions from the September 2021 AUKUS announcement still fresh, now is an important time to develop a mature bilateral relationship with a clear understanding of how interests, priorities and capabilities intersect and diverge. As France looks to increase its presence and contribution in the Indo-Pacific, Australia should take a deliberate and active approach to managing risks and seizing on opportunities to work effectively with French counterparts.

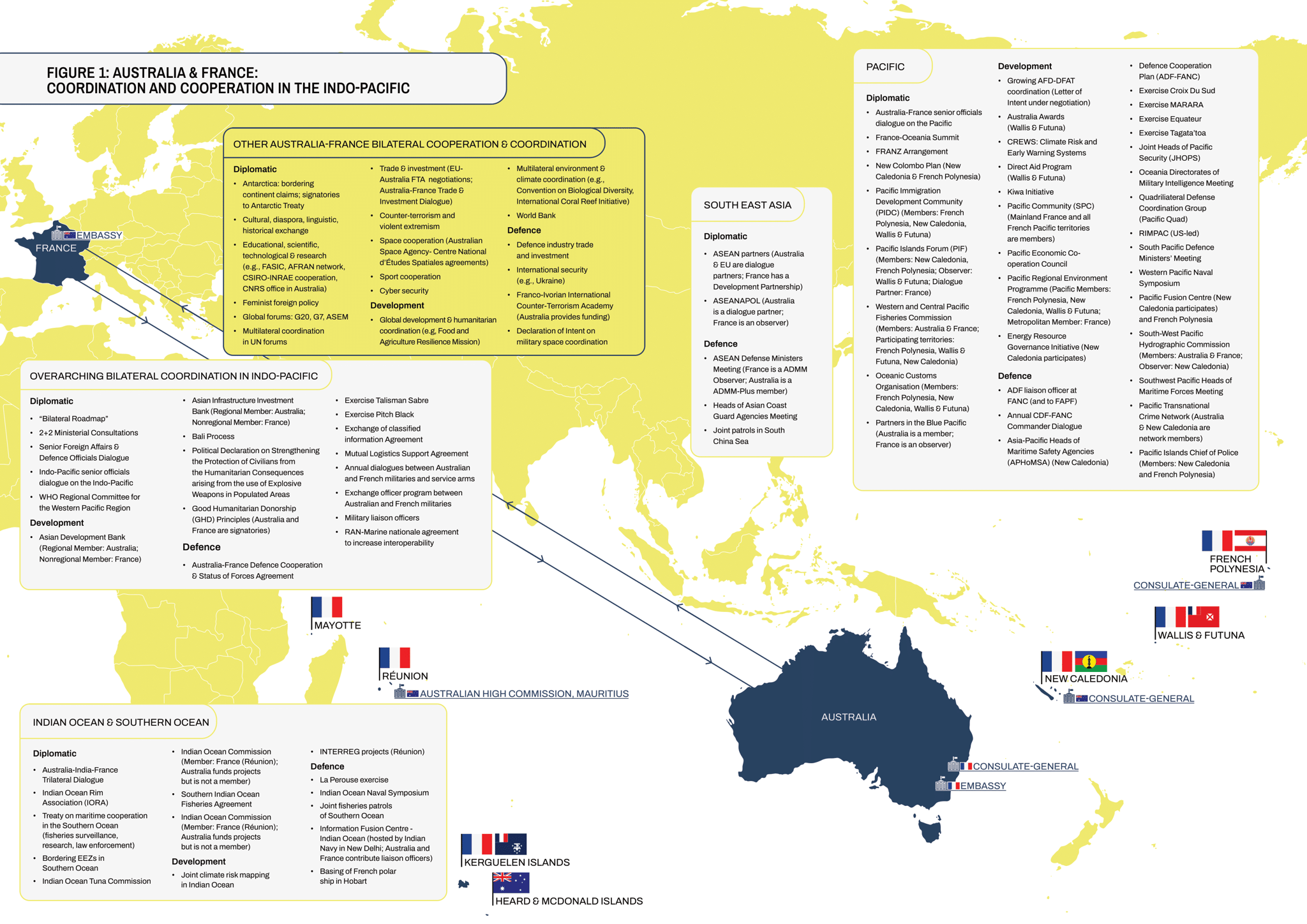

There are already substantial ties and areas of mutual coordination, cooperation and interests between Australia and France across three regional theatres: the Pacific, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. While Australia has a greater all-round presence in the Pacific than France, the balance is more even in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. At the same time, the breadth of Australia-France ties and the complicated nature of managing relationships with both metropolitan France and its Indo-Pacific territories (with varying degrees of autonomy), means that this relationship presents complexities for Australia to navigate.

In terms of the overarching bilateral relationship, the key risks and opportunities for Australia are: continuing to rebuild trust and mutual understanding with France post-AUKUS; developing an understanding of France’s strategic outlook and relative global priorities and how that affects its role in the Indo-Pacific; working with France to encourage a greater European contribution to the Indo-Pacific (especially on infrastructure); and boosting Australia’s capacity to engage France.

In the Pacific, Australia needs to consider greater coordination with France both bilaterally and in the context of other external actors with the aim ensuring that contributions are complementary. Humanitarian responses are a well-established area of joint work with France, especially in the FRANZ arrangement with New Zealand, that could be further optimised. Meanwhile, Australia must be cognisant of how France is perceived in the Pacific and how this affects Australia’s own priorities – especially around a First Nations Foreign Policy.

While both Australia and France are significant actors in Southeast Asia in their own right, there is less scope for coordination, but Australian officials should be alert to opportunities to coordinate with French colleagues in forums such as the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting and to leverage France’s “third way” stance on strategic competition.

In the Indian Ocean, the positive momentum behind trilateral dialogue between Australia, India, and France is a welcome development to enable greater practical coordination, especially on maritime security. There are also opportunities for Australia to make a greater contribution in the western Indian Ocean with modest resourcing by working in partnership with France to align messaging and cooperate on issues such as maritime domain awareness and disinformation.

PATHWAYS TO ENHANCE AUSTRALIA-FRANCE COORDINATION IN THE INDO-PACIFIC

Leverage French and European Union contributions across the Indo-Pacific

Working across the Indo-Pacific, Australia should:

- harness the bilateral roadmap with France to leverage greater French contributions across the region

- work with France to influence European engagement in the Indo-Pacific, especially a greater contribution on infrastructure finance

- work with France on the application of France’s Feminist Foreign Policy in the Indo-Pacific

- enhance the Australian Government’s own France literacy and capability for coordinated engagement

Realise the benefits of greater coordination with France in the Pacific

In the Pacific, Australia should:

- develop deeper coordination with France in the Pacific while encouraging a greater French contribution to addressing regional challenges

- optimise humanitarian assistance and disaster relief coordination through FRANZ

- continue to grow First Nations and Indigenous engagement with French Pacific territories

Keep a watching brief on opportunities to coordinate with France in Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, Australia should:

- pursue ad hoc coordination and collaboration with France where interests and capabilities intersect

- investigate the potential for Australia-Indonesia-France trilateral dialogue and practical cooperation

Work with France to multiply the effects of Australia’s efforts in the Indian Ocean

In the Indian Ocean, Australia should:

- continue to invest in the Australia-India-France Trilateral Dialogue

- explore opportunities to leverage French advantages and capabilities in the western Indian Ocean

Why it Matters

Acting alone, Australia cannot realise its vision for the Indo-Pacific. It must work with partners to align priorities and investments, combine resources and capabilities, and coordinate action and engagement. For Australia, France is one such partner.

A significant power in the region, France regards itself as a “fully-fledged Indo-Pacific country”. It aims “to provide solutions to the security, economic, health, climate and environmental challenges” of regional countries, while wanting the “Indo Pacific to remain an open and inclusive area, with each State observing each other’s sovereignty.” This position – focused on addressing key regional challenges to stability and prosperity while maintaining a favourable balance of power – broadly aligns with that of Australia.

Recent joint statements articulate a high degree of convergence in global and regional outlooks between Australia and France. In a meeting this year, “Ministers emphasised the importance of a strong Franco-Australian partnership to preserve the international order based on the rule of law and to work together to maintain an open, stable, and prosperous Indo-Pacific region where sovereignty and international law are respected.”

While the September 2021 AUKUS announcement led to disruption of Australia-France ties, the last 12 months have seen remarkable progress in rebuilding the relationship at the political, bureaucratic and operational levels. A joint statement announced by Prime Minister Albanese and President Macron in July 2022 instructed officials to develop a detailed “bilateral roadmap” to be delivered before the end of 2022. This signals a positive trajectory, with a particular focus on greater coordination and cooperation in the Indo-Pacific across defence and security, resilience and climate, and education and culture.

Given this political, institutional and strategic momentum towards greater partnership, but with frictions still so fresh in memory, it is more vital than ever that Australia have a clear-sighted understanding of how its interests, priorities and capabilities intersect and, for that matter, diverge with those of France. This is especially important given that France has signalled that it will increase its military presence (especially naval and defence industry), diplomatic representation and development contribution in the region in coming years. Australia must take a deliberate and active approach to manage risks and capitalise on opportunities in this bilateral relationship.

The France relationship has unique complexities and challenges for Australia due to its breadth and geography. Not only does Australia work with France bilaterally across a full suite of diplomatic, development, humanitarian, environmental, multilateral, defence, security and intelligence domains, it also engages the French system both globally (as a North Atlantic security actor, a P5 UN Security Council member and an EU economic power) and locally (as a resident Pacific and Indian Ocean presence). From Australia’s perspective, French politics and strategic culture – including variations between the metropole and its overseas territories, as well as France’s colonial history in the Indo-Pacific – are difficult to grasp fully due to language differences and a generally low level of awareness and knowledge amongst the Australian public.

In seeking out greater coordination and cooperation with France, Australia should look for opportunities where priorities, interests and capabilities align to multiply the effects of its efforts. At the same time, various risks need to be mitigated against, including mutual misunderstandings and divergent operational cultures between Australia and France, as well as a lack of coordination both within the Australian system and in engaging the French system. With France looking to update its strategy towards the Indo-Pacific, Australia should aim to influence this as much as possible.

This Options Paper uses “coordination” to broadly refer to Australia and France deconflicting, aligning or harmonising their respective individual actions. It uses “cooperation” to refer to a higher level of joint action where Australia and France work together on a particular initiative.

For the purposes of this Options Paper, we use the following the geographic definitions:

- ‘Indo-Pacific’ stretches from the far eastern Pacific Ocean to the far western Indian Ocean and encompasses all of Southeast Asia and littoral Asia.

- ‘Pacific’ includes all of the island states and territories in or bordering the Pacific Ocean (though this paper is primarily concerned with the southwestern Pacific).

- ‘Southeast Asia’ includes all ASEAN Member States, Timor-Leste and the maritime domain they share.

- ‘Indian Ocean’ refers to all countries on the rim of the Indian Ocean as well as the maritime space of the ocean itself (though this paper is primarily concerned with the north-eastern Indian Ocean, South Asia and the western Indian Ocean island states and territories.

Existing Coordination

Taken as a whole, the relationship with France is one of Australia’s most comprehensive, building on a long history of engagement, exchange and cooperation stretching back to at least World War I. France’s significant global and European influence, as well as its various territories scattered around the world, including in the Indian Ocean and Pacific, provide unique complexities for Australia’s engagement. France is both a distant European power and proximate resident force. It is also important to remember that various dimensions of French policy (especially economic) are set at the EU level. Moreover, France contributes to the EU’s engagement in the Indo-Pacific and has been the most influential member state in the EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

Figure 1 below captures the institutional avenues for coordination and cooperation between Australia and France in the Indo-Pacific, including shared regional fora. While broader bilateral ties such as trade and investment are noted as important context, they are not the focus of this Options Paper. Australia’s engagement with the European Union is also not included.

Bilateral architecture

The bilateral roadmap under development will be the primary relationship architecture, replacing the effectively defunct Vision Statement of 2018. It is expected to be released in 2023, encompassing three pillars: defence and security; resilience and climate action; and education and culture. Moreover, recent joint statements by leaders and foreign and defence ministers articulate a high degree of convergence between Australia and France on their outlook and interests in regional and international security, climate and the environment, and humanitarian issues.

The January 2023 2+2 consultations flagged that Australia and France will look to collaborate on the following areas: energy transition in the Pacific, including by bringing together research capabilities; greater strategic dialogue to share expertise on the Indo-Pacific; and cultural exchange, including with the Pacific. Greater defence collaboration was also flagged, including strategic dialogue and research, operational and logistic cooperation, and civil space cooperation to support climate analysis and disaster resilience in the Indo-Pacific.

Regional coordination

Figure 1 above demonstrates the depth and diversity of regional coordination and cooperation between Australia and France across the diplomatic, development and defence domains. Both countries are members of several regional fora. In France’s case, the basis for its membership varies between fora – in some cases, metropolitan France is the member; in other instances, it is French territories that are the forum members. The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) illustrates this: New Caledonia and French Polynesia are members; Wallis & Futuna is an observer; and France is a dialogue partner. The varying ‘competency’ of territories such as New Caledonia and French Polynesia to engage with a degree of autonomy in external relations, within overarching French sovereignty and control of defence and foreign affairs, makes engagement with France uniquely complex for all countries. This is particularly so for Australia given both its relationship with metropolitan France and its significant role and presence in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

The extent of existing coordination and cooperation between Australia and France varies between sub-regions. Cumulatively across all domains, Australia-France coordination is most developed in the Pacific. There is substantially less joint activity and shared forums in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.

Thematically, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) work is a significant feature of Australia-France coordination in the region, for instance through the FRANZ Arrangement. Environment and climate are growth areas for coordination, at both the regional and global level. Australia and France are also part of several regional minilateral groupings: with New Zealand in the FRANZ Arrangement; with India in a trilateral dialogue focused on the Indian Ocean; and with New Zealand and the United States on defence and security issues in the Pacific. Defence ties are already extensive and continue to grow. Both countries participate in several regional exercises, including those hosted by Australian and French forces. There is also a comprehensive set of defence agreements enabling dialogue, information sharing and practical cooperation.

A structurally complex bilateral relationship

‘Overseas France’ in the Indo-Pacific consists of various territories spanning the Indian, Southern and Pacific Oceans, with varying degrees of autonomy from metropolitan France and employing different systems of government. La Réunion and Mayotte are overseas departments of France, meaning they have the same status as mainland France. French Polynesia and Wallis & Futuna are officially ‘overseas collectivities’, meaning they have some devolved powers of self-government. New Caledonia is a “sui generis collectivity”, meaning it has a special status and some greater elements of self-government. In New Caledonia, Australia must engage representatives of both the metropolitan French Government and locally elected officials. Smaller territories, such as the French Southern and Antarctic Lands, are designated as “overseas territories” and are directly administered by the French Government given their small permanent populations. Administrative responsibility in the French Government for all of ‘Overseas France’ (as well as French expatriates) sits with the Ministry of the Interior and Overseas.

The Australia-France bilateral relationship spans global, regional and sub-regional layers. An important feature of this bilateral relationship is the multitude of disparate touch points with France across the Australian system. Different parts of DFAT and Defence, as well as technical agencies, engage French counterparts and develop policy with respect to France.

In DFAT, for instance, separate desks work on the core bilateral relationship with mainland France, French Pacific territories, coordination with France in the Pacific, humanitarian cooperation, trade and investment ties, and environment and climate engagement. Australia has diplomatic posts in both mainland France (Paris) and French Pacific territories (Noumea and Papeete). The post in Mauritius is accredited to the Francophone east African island states and has consular responsibility for La Réunion.

Meanwhile, different parts of Defence work on policy towards mainland France and France in the Pacific, defence industry engagement and intelligence cooperation. Each service branch also has its own relationship with French counterparts, as well as there being joint operational engagement. Military engagement in the Indo-Pacific occurs through France’s regional commands in New Caledonia (FANC), French Polynesia (ALPACI & FAPF), and the Southern Zone of the Indian Ocean (FAZSOI), and in the United Arab Emirates covering the rest of the Indian Ocean (FFEAU ALINDIEN). While these commands do not have strategic autonomy from Paris, they are Australia’s closest touch point in the region for defence engagement.

Indo-Pacific engagement snapshot: Australia and France

To understand Australia’s and France’s relative priorities and advantages in the Indo-Pacific, it is important to compare the respective resources and capabilities each can bring to bear in the region. The tables below outline comparative diplomatic, development and defence presence using the proxy measures of diplomatic posts, official development assistance (ODA) spending and the permanent presence of defence personnel and assets.

Taking these measures together, Australia clearly has significantly greater statecraft resources in and oriented towards the Pacific than France. The comparison is more balanced in Southeast Asia. In the Indian Ocean, France has a significantly greater diplomatic footprint and ODA spend, primarily driven by its historically strong presence in the western Indian Ocean. Direct comparison of defence presence between regions in the same way is difficult given different force postures and geography. However, it is clear that Australia has a much greater overall permanent defence presence in the region. France does, however, regularly rotate various military forces and assets through the Indo-Pacific and has liaison officers in various military commands throughout the region.

Comparative permanent defence presence in key regions

Australia

France

Australian Defence Force personnel and assets are primarily located in Australia or the Indo-Pacific by virtue of Australia’s geography and can be projected into the Pacific, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Around 85,000 personnel (including reserves)

100+ aircraft*

*Exact figures are not publicly available. This is a low-range estimation of total aircraft operated across the ADF. The actual number is likely to be significantly greater.

French Armed Forces New Caledonia (FANC)

Southwest Pacific

1,600 personnel

4 naval units

4 transport or surveillance aircraft

4 helicopters

France Pacific Command (ALPACI) & French Armed Forces French Polynesia (FAPF)

East Pacific, North Pacific, Southeast Asia

1,180 personnel

3 naval units

5 transport or surveillance aircraft

3 helicopters

French Armed Forces in the Southern Zone of the Indian Ocean (FAZSOI)

Western Indian Ocean and Southern Ocean

2,000 personnel

5 naval units

2 transport or surveillance aircraft

2 helicopters

Indian Ocean (ALINDIEN Maritime Zone) and French Forces in the United Arab Emirates (FFEAU)

650 personnel

6 fighter planes

1 transport or surveillance aircraft

1 naval base

French Forces in Djibouti (FFDj)

1,450 personnel

4 fighter planes

1 transport or surveillance aircraft

8 helicopters

Figures from France’s Indo-Pacific Strategy and Minister for the Armed Forces Sébastien Lecornu. France is expected to expand its permanent positioning of military assets in the Pacific over coming years, as well as greater rotation of naval assets through the region.

Comparative diplomatic presence in key regions (honorary consuls not included)

Australia

France

Pacific - 19

New Zealand (2), Papua New Guinea (2), Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu

Southeast Asia - 16

Indonesia (4), Thailand (2), Vietnam (2), Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Timor-Leste

Indian Ocean - 8(10) (not including Persian Gulf, Arabian Peninsula, and continental Africa)

India (4 + Bengaluru announced), Bangladesh, Mauritius, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Maldives (announced)

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Pacific - 6

Australia (2), New Zealand, Fiji, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea

Southeast Asia - 11

Vietnam (2), Indonesia, Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar

Indian Ocean - 14 (not including Persian Gulf, Arabian Peninsula, and continental Africa)

India (5), Sri Lanka (2), Pakistan (2), Bangladesh, Mauritius, Madagascar, Comoros, Seychelles

Source: Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs

Comparative Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) spend in key regions

Australia

France

Australian ODA (AUD million) in 2023-24 (by country and region of benefit)

Pacific: $1,906.1

Southeast Asia: $1,237.8

Indonesia, Timor-Leste, Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, Mongolia, regional

Indian Ocean: $285.4

Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Maldives, regional

Direct comparison of Australian and French ODA is difficult given the different reporting approaches between the respective governments, meaning that different years and data sources are employed here. For the purpose of this Options Paper, readers should focus on the macro level spending comparison rather than exact amounts.

French ODA (AUD million) in 2020 (does not include ODA by EU Institutions)

Indonesia, Vietnam, Myanmar, Laos, Philippines, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia

India, Madagascar, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Comoros, Sri Lanka, Mauritius

Direct comparison of Australian and French ODA is difficult given the different reporting approaches between the respective governments, meaning that different years and data sources are employed here. For the purpose of this Options Paper, readers should focus on the macro level spending comparison rather than exact amounts.

* Conversion from USD to AUD based on market rates on 17 May 2023.

Perspectives

As Australia seeks to grow its coordination and cooperation with France in the Indo-Pacific in line with the bilateral roadmap, it must remain mindful of the respective outlooks, constraints and interest of both countries. These considerations set the context for what greater coordination might be possible and how to achieve it.

Status of the Australia-France bilateral relationship

The last five years have been a rollercoaster for Australia-France relations. President Macron’s speech at Garden Island in May 2018 and the first iteration of France’s Indo-Pacific Strategy were a high-water mark, outlining France’s vision for the Indo-Pacific with the relationship with Australia at its centre. But with the cancellation of the French submarine contract in September 2021, relations took a nosedive, including with the recall of the French Ambassador to Australia (the first time this has occurred). This marked the lowest ebb in bilateral relations since French nuclear testing in the Pacific in the 1980s.

Since then, however, a steady process of recovery has ensued. This has been driven by multiple factors including the good faith negotiation and swift compensation for the contract termination; Australia’s ongoing acknowledgement of France as an Indo-Pacific power; the imperative for practical coordination driven by alignment in strategic outlooks; and a more progressive Australian position on climate policy. While not all negative perceptions (on both sides) have fallen away, the overall warming of bilateral ties was cemented when Prime Minister Albanese visited France in July 2022, followed by positive ministerial consultations between both countries’ foreign and defence ministers.

This recent history is important context because it shapes the nature and extent of underlying trust in the bilateral relationship. While creating a lower ceiling on Franco-Australian trust, the 2021 rupture and recovery forced both sides to develop a more honest and realistic understanding of each other and the potential scope for coordination and cooperation. Australia may have miscalculated the importance of the submarines to France’s overarching Indo-Pacific strategy and wider global role. At the same time, France may have come to better understand Australia’s strategic interests and alliance priorities. As both countries now work towards articulating their bilateral roadmap in 2023 and reorienting their respective policies towards each other, there is an opportunity for Australia to influence France’s Indo-Pacific posture and contribution with a clear-eyed view of where interests and capabilities intersect.

In the Indo-Pacific, greater coordination between Australia and France is one instance of the broader challenge of aligning the contributions of various actors to the region’s stability, resilience and prosperity. Right across the region, Australia, France and others – such as India, Japan, the US, Europe, South Korea and New Zealand – all need to understand their relative advantages, deconflict their efforts and work together to multiply effects. Even though this Options Paper focuses specifically on Australia and France, it is important to understand this challenge as representative of the general imperative for coordination in a contested and crowded region. This is especially important given that the many small island developing states and civil society partners throughout the Indo-Pacific have very limited capacity to engage a large number of international partners. A lack of coordination between Australia, France and other actors risks compromising partnerships and the effectiveness of their efforts.

France’s strategic outlook, priorities and capacities in the Indo-Pacific

While there is strong convergence between the two countries’ Indo-Pacific interests and activities, it is just as important for Australia to have a clear understanding of how France’s strategic outlook and relative priorities differ from its own. This is essential for a realistic and focused approach to engagement that seeks to apply limited bandwidth on both sides to the most productive areas.

This starts with a nuanced appreciation of French strategic culture and how it manifests in the Indo-Pacific. Drawing on a Gaullist tradition that privileges French sovereign decision making, independence and autonomy, France under Macron has continued to pursue a status as a puissance d’équilibre – a balancing power – in strategic competition between the US and China. While its interests and actions align far more closely with those of the US and its allies such as Australia, France is firm in its view that it will engage in the world according to this conception of its own interests. Pursuant to this, France has promoted what it calls a “third way” in the Indo-Pacific where it attempts to avoid definitively taking sides in a US-China binary, instead seeking to engage with all parties based on an independent conception of its own interests and assessment of threats.

France is, of course, entitled to pursue its own approach in the Indo-Pacific – and it would be unreasonable for Australia to expect complete alignment with a country as different to it as France. However, Paris’ puissance d’équilibre and explicit attempt to offer a “third way” generate uncertainty for Australia, the US and others whose respective positions are more fixed and closely aligned. In Australian (and American) minds, it has the potential to cast doubts about France’s reliability and consistency as a long term partner in the region to support collective deterrence in both the economic and strategic spheres. Comments by President Macron in April 2023 regarding the French and European position on China and Taiwan, and the response it created in the US and Australia, are symptomatic of this. The critical point for Australia, though, is to recognise how France’s words and actions, while not always perfectly echoing its own, sit within a broader tradition in French strategic culture and worldview. A deeper understanding of this culture and worldview will help Australia manage the risk of misperceiving French policy.

At the same time, France’s more independent stance within strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific offers opportunities for Australia. Working with France where interests and capabilities align may give greater space for Australia to influence parts of the region that are reluctant to be seen to be “taking sides” with either the US or China. In particular, Australia should consider how its language around “strategic equilibrium” might dovetail in particular niche areas with France’s “balancing power” position to engage a broader suite of countries in the Indo-Pacific in a ways that moves beyond a US-China binary.

There may also be openings for Australia and France to coordinate on the substance of messaging but generate greater influence by speaking with different voices and pre-conceptions. For instance, on topics such as human rights, regional relations with China and Russia, awareness of malign foreign influence and maritime security, Australia and France could coordinate their messaging in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.

It is also vital that Australia see France’s Indo-Pacific engagement within the bigger picture of its global commitments. France is a major power in Europe and a significant force in international security. On the one hand, this makes France a valuable partner for Australia, able to bring genuine global reach and influence – as a P5 and G7 member with significant military and economic weight – into the Indo-Pacific in a constructive way. On the other hand, though, Australia should not underestimate how much French bandwidth is consumed by its ongoing role in Africa, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and broader North Atlantic security. For instance, in 2018, 39 per cent of French ODA was directed to Africa (€3.6 billion). Moreover, with most hard assets positioned around metropolitan France, distance prevents their rapid deployment to the Indo-Pacific. There are opportunity costs for France in giving attention and resources to the Indo-Pacific. The French Senate has raised questions about whether France’s resource allocation and depth of strategy in the Indo-Pacific really match its rhetoric, in terms of permanent diplomatic presence, defence commitment and development contribution – especially in the Pacific. There are also doubts over the extent to which French territories in the Indo-Pacific were consulted on, and have bought into, France’s regional strategy.

While these structural limitations will persist, there are signs that France is looking to ramp up its Indo-Pacific role in terms of a greater permanent military presence, an expanded diplomatic footprint (especially in the Pacific), and a larger development contribution in the Pacific. Precisely how and when this plays out remains to be seen. The appointment of dedicated French regional ambassadors for the Indo-Pacific as a whole, as well as for the Pacific and Indian Oceans, indicates this potential trajectory.

Australia should look to identify challenges and geographic areas across the Indo-Pacific where France has particular advantages and capacities that intersect with Australian interests. Thematically, France has strengths it can bring to bear meaningfully in development (such as environmental and climate security and infrastructure) and the governance of territorial waters (such as maritime domain awareness (MDA) and exclusive economic zone (EEZ) monitoring).

Australia could also do more to coordinate its gender equality work in the region with France’s Feminist Foreign Policy approach.

In places where France’s military presence is concentrated, it can also make important contributions to humanitarian responses and maritime security. Geographically, France far outweighs Australia in the western Indian Ocean where it has a historically strong presence and continues to be well-connected diplomatically and makes substantial development contributions alongside the EU. In the Pacific, meanwhile, France is more likely to provide niche offerings that complement Australian and broader regional efforts. In this context, there may be opportunities for coordinated reciprocal burden-sharing between Australia and France across the Indian Ocean and Pacific.

Taken together, these observations about French outlook, priorities and capacities should encourage Australia to approach coordination and cooperation with France in a strategic and nuanced way. A greater awareness of France’s limits and strategic culture will enhance Australia’s ability to pursue avenues of joint work that have high potential without being distracted by those that have less chance of success.

The second key point for Australia is to be cognisant that its own Indo-Pacific perspective and priorities will never completely align with those of France. Whereas Australia is an Indo-Pacific power by nature, France is ultimately one by choice – and will always prioritise European security to the extent that there are trade-offs. Even within the Indo-Pacific frame, France accords greatest priority to the Indian Ocean given its proximity and how directly it engages European economic interests. Consequently, France is less inclined to see the whole Indo-Pacific as a single strategic ecosystem to the same extent that Australia, the US and Japan do, for instance.

With overlapping, but not perfectly aligned, interests, the risk that Australia must manage is ensuring that productive engagement by France in the Indo-Pacific is given sufficient priority amongst the plethora of global concerns both countries share. While engaging France on French priorities gives Australia leverage to influence Paris’ decision making, there is a balance to be struck between relative priorities.

The role of Europe and the European Union

While this Options Paper does not specifically consider the wider European role in the Indo-Pacific, it is important to understand the centrality of France to the EU’s regional engagement. France was the driving force behind the EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, which was developed while France held the presidency of the council of the EU. Moreover, France is the European country whose interests are most directly engaged by, and has by far the greatest permanent presence in, the Indo-Pacific. It is also the EU member state with which Australia has the most substantial ties.

Under the EU Strategy, the “the EU aims to contribute to the region’s stability, security, prosperity and sustainable development, in line with the principles of democracy, rule of law, human rights and international law.” This is through seven priority areas for cooperation: sustainable and inclusive prosperity, green transition, ocean governance, digital governance and partnerships, digital connectivity, security and defence, and human security. Given the broad alignment of the EU’s vision and priorities with Australia’s, there are opportunities to work with France to leverage and influence the EU’s contributions to the region to be as productive and well-coordinated with others as possible. Infrastructure finance is a particularly important area.

Influencing the EU’s commitments and investments in the Indo-Pacific is especially pressing right now given ongoing resource scarcity, the attention consumed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and economic recovery from COVID-19. These pressures could further constrain the EU’s contributions to the Indo-Pacific, in addition to the limits imposed by its consensus-based decision-making model and the bloc’s primarily economic rather than strategic focus. While the overall EU approach to China has hardened in recent years driven by a ‘de-risking’ imperative, there remain divergent views and priorities between member states on Indo-Pacific security and China.

Australia’s capacity for effective France engagement

Broadly, Australians and French are regarded as having a strong interpersonal and cultural affinity. This is driven by high levels of people-to-people and cultural exchange, shared history and liberal-democratic values. However, general public awareness and media coverage of France and its politics and history is poor, at least relative to the country’s significance to Australia. This is even more so for French territories in Australia’s near region. There are also currently very few university and think tank resources in Australia devoted to investigating French foreign policy.

Within government, coordination on France-related engagement and policy is generally good, though largely informal and ad hoc. The various parts of the Australian system that engage France or work on France-related policy generally have an awareness of their place within the bigger picture of the bilateral relationship and who their counterparts across government are. While French is a common second language for Australian bureaucrats and ADF officers, the depth of knowledge about France’s politics, history, literature and strategic culture is inconsistent – in particular, an appreciation for the nuance of metropolitan France vis-à-vis its Indo-Pacific territories. It is worth considering a more deliberate approach to harnessing latent “France literacy” across government and adopting more structured means of coordinating policy and engagement given the breadth and complexity of the bilateral relationship.

"Australia warmly welcomes France’s cooperation in the Indo-Pacific and its strategy for further engaging the region as well as the European Union’s Indo-Pacific Strategy and its commitment to long-term investment in the region."

Barriers and Opportunities

PACIFIC

Coordination imperative in the Pacific

As geopolitics drives a crowding-in of external actors in the Pacific, there is a need for such actors – including Australia and France – to coordinate with each other more effectively. At the same time, better coordination must be done in a consultative and respectful manner in partnership with Pacific nations.

Coordination and deconfliction are crucial for maximising the impact of scarce resources and ensuring that the often-limited bandwidth of Pacific governments is not overwhelmed by managing external actors. Playing to the respective strengths of different actors, drawing on collective expertise, and avoiding duplicating or undermining respective efforts are also crucial. While the geopolitical motivations of external actors are inevitable, coordination – and in some cases active collaboration – between them can help minimise its impact. A well-coordinated approach between external actors is more likely to generate dividends in terms of political influence.

Australia and France can work to improve coordination, alongside other actors including the US, New Zealand, Japan, EU institutions, multilateral development banks and European countries. While it is yet to demonstrate its practical value fully, the Partners in the Blue Pacific initiative promises to perform such a function – though France and the EU are only observers of this group, and it has received a mixed reception in the Pacific.

With the upwards trajectory of Australian and French diplomatic presence and development contributions in the Pacific, there will be a growing need for both countries to work more closely together and in partnership with the Pacific. With EU institutions and individual European nations such as Germany and the UK also looking to boost their contributions to the Pacific, there may also be opportunities for Australia and France working together to play an organising role, advising these actors on how best to bring their capacities to bear.

Donor coordination forums and conferences, greater visibility and mapping of respective contributions, alignment on diligence and compliance requirements, and dedicated resources for coordination are all ideas to explore in this respect. As much as possible, Australia should be encouraging any greater French (and European) contributions to be channelled through existing structures and institutions.

Currently, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) best demonstrates the coordination imperative for external contributions to the region’s most immediate challenges. FRANZ, a tripartite arrangement between France, Australia and New Zealand for immediate recovery and relief efforts in the Pacific, has demonstrated its value over recent years in coordinating assets, resources, and efforts between the three nations in response to natural disasters and COVID-19 in Vanuatu, Tonga, Fiji and Papua New Guinea. As the three most proximate actors with the capability to make significant HADR contributions, FRANZ illustrates the value of structures for coordination that can enable effective burden-sharing.

With the demand for HADR in the Pacific likely to grow due to climate change, it will be important for the FRANZ partners to consider how to optimise the arrangement, enhance its operational effectiveness, and work more consistently under Pacific leadership and with other external actors such as the US and the UN. Strong and ongoing participation by Australian forces and personnel in the French-led Exercise Croix Du Sud is an important regular opportunity to develop relationships and habits of cooperation on humanitarian responses in the Pacific. Australia and France should also identify opportunities to derive lessons from humanitarian response coordination mechanisms to inform coordination in other sectors.

Australia-France coordination in the Pacific

With the French development agency – Agence Française de Développement (AFD) – on a trajectory to increase its presence and contribution in the Pacific, there will be a growing need for coordination between Australia and France in approaches to development. The greater AFD contribution will likely be focused on infrastructure, environment, oceans and climate resilience. There is, however, very little history or established patterns of coordination or cooperation between Australia and France in the Pacific on development. What coordination has occurred has been ad hoc and contingent on particular circumstances and relationships. This reflects the status quo where French spending in the Pacific is concentrated on its own territories and through the Pacific Community (SPC).

There are substantial barriers to joint work on particular development projects between Australia and France given unfamiliar bureaucracies and different languages, ways of working and approaches to financing. Moreover, AFD mostly focuses on development finance, namely loans, rather than grants. Feasible bilateral cooperation is most likely to be in the form of discrete contributions, such as co-financing by one side of a project run by another – for instance, the financial contribution Australia makes to the French-run Kiwa Initiative. The priority for Australia, then, should be in building habits of coordination and institutionalising dialogue with France to ensure respective contributions are complementary. In this respect, it is a positive development that DFAT and AFD are presently working on a letter of intent.

Shared interests and capacities in MDA and EEZ monitoring, education and research (especially in marine science), blue economy, infrastructure and defence interoperability all present avenues for greater coordination and potential cooperation. On the maritime front, Australia should consider how France could expand its efforts beyond patrolling its own EEZs and contribute more to existing maritime security efforts.

In working more closely with France in the Pacific, Australia needs to ensure any coordination is driven by the region’s enduring needs, as articulated within the “Blue Pacific” concept. The Pacific should not be framed as an object of strategic competition.

France’s status in the Pacific

The broadly-held (though not universal) view in Australian policymaking circles is that France is a stabilising status quo power in the Pacific whose ongoing presence and growing engagement is desirable and should be encouraged to the extent that it serves Australian interests. A greater French diplomatic, military and development contribution throughout the Pacific generally should be supported, with Australia seeking to influence its direction, tenor and content as much as possible.

However, there are risks and sensitivities that Australia must confront and manage in frank terms. The first is around the complexity of managing relationships with the semi-autonomous French territories in the Pacific – in particular, how New Caledonia and French Polynesia engage in forums such as the PIF on essentially the same terms as sovereign nations, even though foreign relations and other key policy domains remain under the purview of Paris. Australia needs to be cognisant of how interests and perspectives can diverge between overseas and metropolitan France and sensitively navigate this complexity over time. Australia wants to maintain good relationships with both Paris and local authorities and populations in French territories – not least because those territories might one day become independent nations.

The second risk lies in how France acts and is perceived in the Pacific. In some parts of the region, especially Melanesia, there are people who express resentment and distrust over France’s colonial history and ongoing sovereignty over parts of the Pacific. Memories regarding French nuclear testing are also an important consideration in Polynesia. Developments in recent years around New Caledonia’s status, especially the 2021 independence referendum, have added to this. More broadly, French engagement in the Pacific is often regarded as inconsistent and has a different tone to that of Australia in its engagement with local conditions and sensitivities. There are risks to Australia’s own relationships and equities in the Pacific if it perceived as being too close or sympathetic to France, or if it uncritically accepts all French positions. Consultations in the Pacific (see table below) illustrate the importance of these issues.

Moreover, the wider context of the Australian Government’s push towards a First Nations Foreign Policy and its willingness to speak openly about the legacy of colonialism in the Indo-Pacific must be considered in the context of engaging France in the Pacific. There is a reputational risk for Australia were it to be conspicuously inactive on Indigenous issues with respect to the French territories while engaging with such issues elsewhere. While it is clear that the Australian Government intends to remain neutral as to the future status of French territories, it must be cognisant of, and proactive in, managing these risks while at the same time maintaining a close relationship with metropolitan France. This is also important for the credibility of Australia’s First Nations Foreign Policy.

Pacific Voices

To understand Pacific perspectives on the potential for greater Australia-France coordination, we conducted discussions with people in Vanuatu, Fiji and Tonga with experience and insights from working with both Australia and France.75 We have synthesised their views here.

Perceptions of France

Across the three countries surveyed, France was regarded as having the strongest and most consistent presence in Vanuatu by a significant margin. There remain strong negative perceptions, especially in Fiji, about France’s colonial legacy and ongoing presence in New Caledonia and French Polynesia. In terms of France’s approach to development in the Pacific, across all countries this is seen as being more top-down, with less engagement with local needs and preferences when compared to Australia’s agenda focused on localisation and sustainability. A widely held perception of lower French cultural and linguistic competency in the Pacific further hinders this. Consequently, Pacific voices identified risks for Australia in being seen to uncritically align itself too closely with France.

Views on greater Australia-France coordination in the Pacific

Humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) was identified as the most advanced and effective area of existing Australia-France coordination, especially in the recent context of FRANZ responses to tropical cyclones in Vanuatu. While dialogue and joint working has been strong, Pacific voices identified that HADR responses could be improved with deeper local political economy analysis and consultation with local people and existing local structures.

In terms of broader development contributions beyond emergencies, Pacific voices said there was significant scope for Australia and France to coordinate more effectively, while coming from a very low base of existing cooperation and coordination. Greater dialogue, information sharing, planning and consultation with locals should be prioritised in-country. A clear commitment to coordination by Australia and France, along with other external contributors, would also mitigate the “donor overcrowding” problem and help manage the workload of small Pacific bureaucracies. Indeed, it would be to Australia and France’s mutual credit to lead increased coordination, helping demonstrate a commitment to being “responsible donors” responsive to local contexts and needs.

At the same time, some Pacific voices also noted the risk for Australia in working too closely with France and EU institutions as this may lead to a reduction in the flexibility and responsiveness for which Australia is highly valued. Engaging with, and accessing funding from, the EU is widely seen to be onerous, highly bureaucratic, and operationally decontextualised.

In the (officially) trilingual context of Vanuatu, there is a particular imperative for better coordination between Australia and France. The tendency of both countries to work within their respective Anglophone and Francophone contexts can reinforce negative divisions and hinder efforts towards a unified nation-building agenda. This is particularly the case in Vanuatu’s education system which bears a high degree of resource-intensiveness based on its colonial history. Vanuatu voices called for greater resource pooling and joint planning between Australia and France to help mitigate this.

Areas identified for potential joint work between Australia and France

Pacific voices identified several areas where they believe joint work between Australia and France could be beneficial to their countries:

- Support for local media and civil society

- Advancing gender equality

- Sports development

- Education

- Infrastructure (especially in attracting and coordinating EU finance)

Focus group discussions were held in Vanuatu, Fiji and Tonga with ten people with experience engaging or working with the French and Australian Governments.

SOUTHEAST ASIA

Southeast Asia is the sub-region of the Indo-Pacific where there is the least potential for greater coordination and cooperation between Australia and France. While both countries have a significant presence in this region in their own right, Australia and France are less significant actors in Southeast Asia relative to other major partners of the region and there are fewer structural reasons for close bilateral coordination and cooperation.

In Southeast Asia, Australia should adopt a “watching brief” approach to working more closely with France, having an awareness of where interests and capabilities might align and shared ASEAN fora where coordination might be mutually beneficial. The most likely area for further cooperation is in maritime security, building on joint transits in the South China Sea as well as mutual interests and capacities in MDA and EEZ maintenance. Opportunities for coordination in the context of the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting (ADMM) and its working groups could also be explored, given that France is an observer and Australia a member of ADMM-Plus. Australia and France could also help support ASEAN and individual Southeast Asian countries by coordinating their pressure on the military government in Myanmar. Scope for greater engagement with Southeast Asia by the Australia-India-France Trilateral Dialogue (discussed further below) should also be considered, drawing on the Quad’s similar efforts.

There may also be opportunities for Australia, with its “strategic equilibrium” narrative, to work with France and its “third way” stance to coordinate messaging from different perspectives and work with Southeast Asian countries that are hesitant to explicitly be seen to take a side in US-China competition. Australia and France could identify how these positions align with ASEAN’s Outlook on the Indo-Pacific and Southeast Asia’s predominant focus on its economic outlook.

One important point of context is that France’s request to join the Five Power Defence Arrangement (FPDA) – a security consultation and cooperation mechanism comprising Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and the UK – was rejected in 2017. The French exclusion from this grouping may attract new significance for Australia-France defence cooperation in Southeast Asia in light of AUKUS.

INDIAN OCEAN

A fractured region with asymmetric Australian and French interests

The context for Australia-France coordination in the Indian Ocean is that the region as a whole lacks cohesion and a shared identity – despite the convergence of challenges its littoral states face. In many respects, the region is better understood as a loose collection of sub-regional groupings: Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Africa, and periphery actors such as Australia and France.

Reflecting the disparate geography and fractured nature of this region, Australia and France’s interests and capacities vary across it. Australia is currently focused more on the north and northeast, especially the Indian subcontinent, and retains a very small presence in the western Indian Ocean island states. France, meanwhile, is a significant power in the western Indian Ocean owing to its historic role, Francophone links, and overseas territories. It also has significant ties with India, especially in defence.

Regional architecture

A broader symptom of the Indian Ocean’s fractured nature is the general weakness of its regional architecture, especially the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) – of which both Australia and France are members. IORA is considered to be under-resourced, with a generally low level of buy-in from member states. The means IORA and other regional institutions (to the extent that they exist) are presently not well-equipped to help organise responses to their priority areas including maritime safety and security, fisheries management, disaster risk management, scientific and technology cooperation, and blue economy.

As IORA member states with a shared interest in regional stability, Australia and France need to be pragmatic about the limitations of IORA while also reinforcing (or at least not undermining) its status as the premier Indian Ocean regional forum. In some instances it will make most sense for Australia and France to work bilaterally, in smaller more coherent groupings, or through other institutions such as the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC). Where possible, however, working through IORA should be prioritised to bolster its centrality. This is especially important given Beijing’s attempts to establish alternative China-centric regional architecture for the Indian Ocean.

Potential in the Australia-India-France Trilateral

The most advanced small group is the Australia-India-France Trilateral Dialogue. This is an important, high-potential grouping for Australia with a clear alignment of interests and capabilities – especially in the maritime domain – in the Indian Ocean. While the trilateral was put on ice by France after the September 2021 AUKUS announcement, its return in 2022 demonstrates the strong convergence of interests and political momentum behind it. There is significant potential for the three countries to work together to provide public goods for the region in response to non-conventional security threats.

Opportunities for Australia to work with France in the western Indian Ocean

Given France’s significant contributions and expertise in the western Indian Ocean, there is an opportunity to work with French counterparts to multiply the impact of Australia’s relatively modest presence. While on the far western periphery of the Indo-Pacific, Australian interests are engaged in these island states – Mauritius, Comoros, Madagascar and Seychelles – in important ways. This sub-region is a source of maritime insecurity in the region, especially in terms of transnational crime, and is an arena for strategic competition with the US, India, China and Russia all active. While the balance of power in this part of the Indian Ocean has been favourable, or at least benign, to Australian interests for a long time, growing Chinese influence and the potential for changes to the status of Diego Garcia might present future strategic risks for Australia to manage. The area is also an important and contested source of marine and mineral resources. Moreover, with Australia currently pursuing bids to host COP31 in 2026 and for a UN Security Council seat in 2029-30, it is important that it actively builds relations with small island developing states.

Working with France bilaterally also provides diversity to Australia’s key Indian Ocean relationships beyond India. India should not be Australia’s only comprehensive partner in the region, given concerns in some parts of the Indian Ocean about New Delhi’s influence.

Australia is a generally well-regarded and valued actor in the western Indian Ocean. However, its modest presence and contribution in the western Indian Ocean can sometimes be conspicuous, especially relative to Australia’s recent step-up in the Pacific and with local memories of greater contributions in previous decades. With one small post in Mauritius covering the entire sub-region, equipped with only a small development budget, Australia must find ways to maximise its impact with limited resources. Greater information-sharing and coordination of messaging with France, as well as strategic contributions to French or EU-led initiatives, could provide opportunities to multiply Australian influence.

Australia has the ability to convey aligned messaging with a different voice, given that it does not carry the same historical baggage as other external actors – like France, the UK and the US – in the western Indian Ocean. At the same time, however, as in the Pacific, Australia must be careful to avoid being seen to be too close to France to preserve its independent influence. Australia could also offer valuable capacity-building resources in combination with France in maritime security and safety, including for the region’s fusion centres, and potentially in other areas such as countering disinformation.

The common interests and challenges of small islands developing states in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific is an area where Australia and France are uniquely well-placed to help facilitate information exchange, dialogue and capacity-building. As significant developed countries in both regions that cover their two main working languages (English and French), Australia and France could look to identify key areas, such as fisheries management, where there are clear benefits to supporting inter-regional exchanges.

The Vision in Practice

What does it look like for Australia to enhance coordination with France in the Indo-Pacific?

Australia capitalises on the current positive trajectory to build a constructive relationship with France over the medium to long term. Following on from the agreement of a bilateral roadmap, both countries prioritise coordination in the Indo-Pacific and deepen this over time as the roadmap is implemented. Key areas of mutual interest and capability are identified, building on a high degree of convergence in strategic outlooks.

With Australia’s encouragement and advice, France follows through on its commitments to make greater contributions across diplomatic, development and defence domains in the region, especially in the Pacific. Both Australia and France continue to develop a better sense of each other’s relative priorities and capabilities in the Indo-Pacific, meaning the relationship matures based on a pragmatic mutual understanding of where coordination and cooperation will be most productive and best aligned. The Australian Government becomes more sophisticated in its appreciation of French strategic culture and more adept at navigating this bilateral relationship.

In the Pacific, an expanded French presence makes constructive contributions to addressing the region’s challenges, including through effective coordination with Australia and other external actors. With natural disasters unfortunately remaining regular, the FRANZ Arrangement continues to be a valuable coordination mechanism in immediate HADR efforts, improving its ability to work with Pacific leadership in post-disaster situations. Australia maintains and grows its ties with Indigenous people in French Pacific territories, while managing related sensitivities in the bilateral relationship.

In Southeast Asia, Australian officials are alert to opportunities to coordinate with France, including in ASEAN forums and on maritime security. The potential for trilateral exchanges between Australia, Indonesia and France is explored.

In the Indian Ocean, the Australia-India-France Trilateral Dialogue continues to grow in shared political significance and is given substance by practical cooperation to address non-conventional security problems. Meanwhile, Australia leverages its ties with France to exert greater influence in the western Indian Ocean, identifying particular areas such as maritime security and safety where niche Australian contributions to French or EU-led efforts are worthwhile.

Australia and France both recognise that they are uniquely well-positioned to jointly facilitate inter-regional exchanges between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, given their significant presence across the two oceans.

Pathways

Overarching Indo-Pacific: Leverage French and EU Contributions

Harness the bilateral roadmap to leverage French contributions to the Indo-Pacific

While the bilateral roadmap is yet to be released, the areas flagged for collaboration between Australia and France are comprehensive and should continue to be pursued. As the roadmap is finalised and then implemented, Australia should prioritise Indo-Pacific engagement as much as possible in the broad agenda of bilateral work.

Australia should look to structure the 2+2 Ministerial Consultations, and the senior officials dialogue that will support it, in a way that prioritises discussion of respective outlooks on the Indo-Pacific and that enables identification of areas of practical coordination and cooperation across the region. While engagement on broader bilateral issues is important, Australia should be looking to focus

French attention and resourcing as much as possible on the Indo-Pacific.

While momentum in the Australia-France relationship is driven by shared interests and overlapping strategic outlooks, Australia should ensure that the bilateral roadmap (and its implementation) is framed around meeting the needs of the Indo-Pacific region while working in partnership with it. Premising Australia-France joint work solely in terms of strategic competition will be counterproductive to effective coordination and relational influence, especially in the Pacific.

By structuring dialogue by sub-regions – Pacific, Southeast Asia and Indian Ocean – Australia and France can take a broad view of their respective priorities, interests and capabilities, and how they might interact. In particular, the asymmetry between Australia’s and France’s respective roles and contributions in the Pacific and western Indian Ocean could be an opportunity for reciprocal coordination. With Australia the more significant actor in the Pacific supporting enhanced French engagement, in turn France might support and help magnify Australia’s modest contributions in the western Indian Ocean. For instance, in terms of defence cooperation, continuing to boost reciprocal access for Australian and French forces to respective bases across the Pacific and Indian Oceans would be a positive development, enabling greater mutual contributions in each other’s areas of greatest presence.

Further, given the common challenges faced by small island developing states in the Pacific and Indian Ocean, Australia and France are natural partners in helping facilitate exchanges between these two regions. Australia could work with France and interested countries to identify specific topics where inter-regional dialogue and collaboration would yield practical benefits. Maritime security and safety, oceans governance, fisheries management and building climate and environmental resilience are topics with high potential.

Work with France to influence European engagement in the Indo-Pacific, especially on infrastructure finance

Australia should be working closely with France to encourage and shape a greater contribution to the Indo-Pacific from the EU and other European actors.

Infrastructure development finance should be prioritised as a high-potential area given both the enormous regional demand for infrastructure and the mutual interest of Australia, France and other European actors. The EU and its member states acting bilaterally are collectively the second largest OECD infrastructure finance provider in the Indo-Pacific, outstripping Australia significantly. In the Pacific, however, Australia makes a significantly larger contribution than Europe.

Moreover, the EU and Europe have advanced established capabilities in infrastructure finance through institutions such as the European Investment Bank. The scale of potential greater European investment in infrastructure is demonstrated by the Global Gateway, a €300 billion pool of EU and Member States’ funds for financing infrastructure across various sectors over 2021-27: digital, climate, energy, transports, health, education and research.

Australia should work with France to influence the decisions of EU institutions and European countries to direct their resources to the Indo-Pacific as much as possible. In particular, a greater European contribution to infrastructure in the Pacific would be welcome. Given the diversity of infrastructure needs in the Indo-Pacific and differences between sub-regions, it is vital that Australia and France coordinate closely with the EU and other European actors. Mechanisms to institutionalise such coordination should be prioritised as part of any greater European role.

Work with France on the application of France’s feminist foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific.

France has held a commitment to feminist foreign policy since 2019, extending to all areas of foreign policy including “reduction of inequality, sustainable development, peace and security, defence and promotion of fundamental rights, and climate and economic issues”, as well as internal objectives around representation and working conditions. As the first P5 Security Council member to adopt this approach, France has played an important role in bringing feminist practice into global foreign policy discourse, including through its 2019 G7 presidency and 2022 EU presidency.

There are promising opportunities for France and Australia to collaborate on the shared objective of advancing gender equality and women’s rights, and to extend France’s feminist foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific.

France has made significant contributions to advancing women’s rights through multilateral forums, an increasingly challenging task as many spaces have become bogged down by anti-rights actors. In 2021, France co-hosted the Generation Equality Forum (GEF), established by UN Women as an alternative to holding a 5th World Conference on Women. The GEF was designed as an alternative space to advance gender equality and women’s rights and generated USD40 billion in progressive, feminist commitments from governments, the private sector and civil society.

Australia has prioritised the defence and advancement of women’s rights and gender equality commitments in international fora such as the Human Rights Council, Commission on Population and Development and Commission on the Status of Women, where France tends to negotiate as part of the EU bloc, while Australia joins a grouping of including Iceland, Liechtenstein, Canada, Norway and New Zealand (colloquially known as the ‘Mountains Group’). Greater cooperation across these blocs would support greater defence of already agreed gender equality principles in increasingly contested multilateral fora.

In international development, France and Australia should engage in greater coordination of efforts to support feminist organisations and movements, and share learning across regions. France’s Support Fund for Feminist Organisations (FSOF) has mobilised more than €138 million in funding from across AFD programs to support the work of feminist civil society organisations in French cooperation partner countries. In line with France’s regional focus, it dedicates 65 per cent of funding to organisations based in Africa. Much of the FSOF is channelled through French and international NGOs. Reaching feminist movements (as opposed to individual organisations) has been identified as an area for growth.

Given DFAT’s focus on increasing locally-led development efforts, including exploration of new models of direct funding to Global South feminist organisations through the Amplify. Invest. Reach. (A-I-R) feminist funds program and initiatives like Balance of Power which recognise the importance of local leadership and knowledge to transform social and gender norms, France and Australia could share lessons on support for feminist movements, and extend their reach across regions.

Enhance the Australian government’s France literacy and capability for coordinated engagement

Given the breadth and complexity of the bilateral relationship and the imperative to promote greater coherence across the Australian system in how it engages the French system, the Australian Government should consider how its own relational infrastructure and approach might be enhanced. While France is one amongst several priority bilateral relationships for Australia, its unique characteristics mean that a very deliberate approach to building capability is required.

The Australian Government should consider:

- Developing a more formal structure for coordinating France policy and engagement across government. This could take the form of a quarterly meeting or a standing interdepartmental committee that includes relevant posts, DFAT desks, and parts of Defence that engage French counterparts regularly, with other parts of government contributing as needed. Such a structure would help institutionalise the sharing of insights between the disparate parts of the Australian system that engage France and provide a regular pattern for coordinating messaging and actions to influence France.

- Making a modest investment in better harnessing “France literacy” in government, including language skills and in-depth knowledge of French politics, history and strategic culture. This should encompass both metropolitan France and French territories in the Indo-Pacific, especially New Caledonia and French Polynesia. Investing in developing a deeper internal understanding of independence movements in these territories would also help Australia foresee and manage risks around its engagement with France and the Pacific territories. “France literacy” should be regarded as a skillset not just valuable for working directly on the bilateral relationship, but also for addressing broader Indo-Pacific challenges in coordination with other states including France. Staff with in-depth experience working on France should be given structured opportunities to consolidate and share their knowledge.

"France is a liberal democracy in the Indo-Pacific, which shares a vision of a globe which is governed by a global rules-based order. And in that sense, as our closest neighbour, France is really in the very top tier of relationships that Australia has with any country in the world."

Pacific: Realise the benefits of greater coordination with France

Develop deeper coordination with France in the Pacific while encouraging a greater contribution to addressing regional challenges

Diplomatic

Australia should work with France to ensure any joint work or coordination in the Pacific is driven by, and responds to, the priorities of Pacific nations and is developed in consultation with Pacific leaders and agencies. Framing coordination or cooperation in the Pacific within a broader narrative of Indo-Pacific strategic competition should be avoided. Instead, the language and ethos of the ‘Blue Pacific Continent’ should be employed as much as possible.

Greater coordination would be enabled by a larger French diplomatic presence across the Pacific. Australia should continue to encourage France to increase its resident diplomatic presence across so that it becomes a more engaged and knowledgeable actor in the Pacific. In particular, Australia should encourage France to invest in developing deeper Pacific expertise and linguistic competency, as well as help facilitate greater French engagement in regional fora, programs and initiatives where France can make a constructive contribution.

Australia should also continue to support the integration of French territories into the regional architecture and economy as much as possible, noting the sensitivities and limitations around the territories’ agency to engage in external relations.

Defence

With France committing to bolster its resident military presence in the Pacific, Australia should continue to identify ways that French forces can constructively contribute more to existing regional maritime security efforts. In particular, Australia should encourage France to make a more substantial contribution to MDA and EEZ monitoring outside of its own sovereign waters, including on responding to illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. One option would be to find ways for French forces to support and feed into the Pacific Maritime Security Program. This could include: conducting aerial surveillance, providing training and capacity building for Pacific maritime forces or contributing to maintenance and sustainment.

Australia should also continue to encourage France to expand its network of resident Defence Attachés across the Pacific. This would help France develop deeper defence relationships in the region and enhance its ability to understand the security needs of Pacific nations.

Development

Broadly, Australia should encourage France to follow through on growing its development contribution in the Pacific, especially on environment and climate resilience.

Bilateral coordination mechanisms and regular dialogue between Australian and French officials should be established as soon as possible, including by finalising a letter of intent with France’s development agency (AFD). Effective communication and information-sharing between Australian and French capitals, as well as in-country between Australian and French diplomatic posts and with Pacific governments, will be important to de-conflict efforts and seek complementarity.

As France looks to increase its development contribution in the Pacific, Australia should encourage French efforts to be channelled through existing coordination mechanisms and institutions.

While France is only an observer of the Partners in the Blue Pacific initiative, Australia should ensure that the grouping remains open to, and engaged with, France as much as possible. Given that the first substantial focus area for Partners in the Blue Pacific is IUU fishing, it is especially important for France to remain engaged given its substantial EEZs in the Pacific and capacity to contribute to MDA.

More broadly, Australia should encourage France to direct its development contributions in the Pacific through NGOs, civil society organisations and multilateral institutions as much as possible. Greater funding for, and engagement with, the SPC would be a prime candidate given that it is headquartered in New Caledonia and has French as an official language. Channelling greater French contributions through the Asian Development Bank and World Bank institutions should also be encouraged.

In terms of specific initiatives, Australia should consider increasing its contribution to the French-run Kiwa Initiative in the Pacific. Australia should also be in active dialogue with AFD about the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP) to explore the potential for collaboration, including French financial contributions.

With EU institutions and other European countries also looking to increase their development contributions in the Pacific, Australia should consider how it could productively partner with France to inform and influence these investments and potentially play a strong convening and coordination role.