What does it look like for Australia to be an...

Effective Partner in Combatting Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing

Published: April 2023

Executive Summary

Combatting illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU fishing) is about supporting the integrity of the international legal framework and the rules-based international order. It is in Australia’s national interest to have regulated rather than unregulated spaces.

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing has many dimensions and impacts ecosystems, economies, human security, international law, governance and human development. Climate change, and the conflict associated with it, will have a significant impact. New challenges mean Australia needs to reset how it looks at IUU fishing, requiring strong cooperation and engagement with partners.

Combatting IUU fishing is a top priority for Indo-Pacific states. Different parts of the region face different challenges, meaning Australia should focus its attention on the elements that are the highest priorities in each. The Pacific is focused on addressing the ongoing challenges of underreporting and misreporting, while littoral ASEAN member states are most concerned with maritime boundary disputes and sustainable fisheries management. Australia can broaden its partnerships into the Indian Ocean, where it has had significantly less engagement. There is scope for Australia to use its unique position as a strong partner in regional fisheries management organisations to share lessons from across the Southern, Pacific and Indian Oceans and Southeast Asia.

Australia can be a global leader in sustainable fisheries management, including maritime domain awareness (MDA), monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) and fisheries science. Australia has much to offer regionally and globally. In the past it has led significant and successful efforts to combat IUU fishing. With renewed focus, Australia can build upon its strong record in promoting sustainable fisheries cooperation.

Being a good global citizen starts at home, with Australia strengthening its domestic regulation to demonstrate best practice. Australia can set an example in its own policies, for example by ensuring that only legitimate catches enter the Australian seafood supply chain.

Fisheries management is a whole-of-government issue linking security, trade, foreign policy and development cooperation. It requires coordination across all the tools of statecraft.

Pathways

AP4D consultations identified four overarching pathways for Australia to be an effective partner in combatting IUU fishing.

Deepening and Broadening Partnerships

- Build global engagement and leadership through strengthened engagement in bilateral and multilateral cooperation

- Retain existing areas of focus on Southern Ocean fisheries, continue to deepen engagement in the Pacific and remain engaged in Southeast Asia, for example through creating a track 1.5 dialogue on IUU fishing

- Broaden partnerships into the Indian Ocean, including through the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), and build relationships with like-minded partners

Adopting Best Practice in Domestic Regulation

- Improve transparency in its own domestic seafood supply chain

- Strengthen regulations to improve transparency on beneficial ownership and open-source data

- Lead by example in reducing industry subsidies, including the diesel excise rebate scheme

Continuing to Invest in Capacity-Building

- Undertake a capacity needs assessment of partners to develop targeted programs and assist Australia’s understanding of regional IUU fishing issues

- Provide training to support implementation of the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation Legislative Guide on Combatting Crimes in the Fisheries Sector

- Design and invest in a major fisheries and marine conservation program for Southeast Asia, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean

- Offer an Australia Awards ‘Women in Leadership in the Security Sector Short Term Award’ to the region with a strong focus on combatting IUU fishing

- Extend and tailor the Australian-accredited monitoring control and surveillance (MCS) training course to Indian Ocean and Pacific participants

Promoting Innovation in Information Gathering

- Integrate new technology to use in collecting data

- Implement a project to map all legislation and regulation that relates to fisheries across the region

Why it Matters

Australia can be a global leader in sustainable fisheries management, including maritime domain awareness (MDA), monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) and fisheries science. An example of the impact of Australia’s leadership is the recent agreement of the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdictions Treaty (High Seas Treaty), an Australian-backed global treaty to conserve the world’s high seas and ensure they are used sustainably.

Australia is a proven leader with international recognition in important areas such as fisheries compliance management. In areas including fisheries science, information management, maritime protection areas, maritime surveillance and enforcement and sustainable returns from the use of fisheries resources, Australia has insight into what works and what doesn’t and is in an excellent position to provide leadership in this area, with sophisticated information, skills and capacity-building knowledge to support countries in the region.

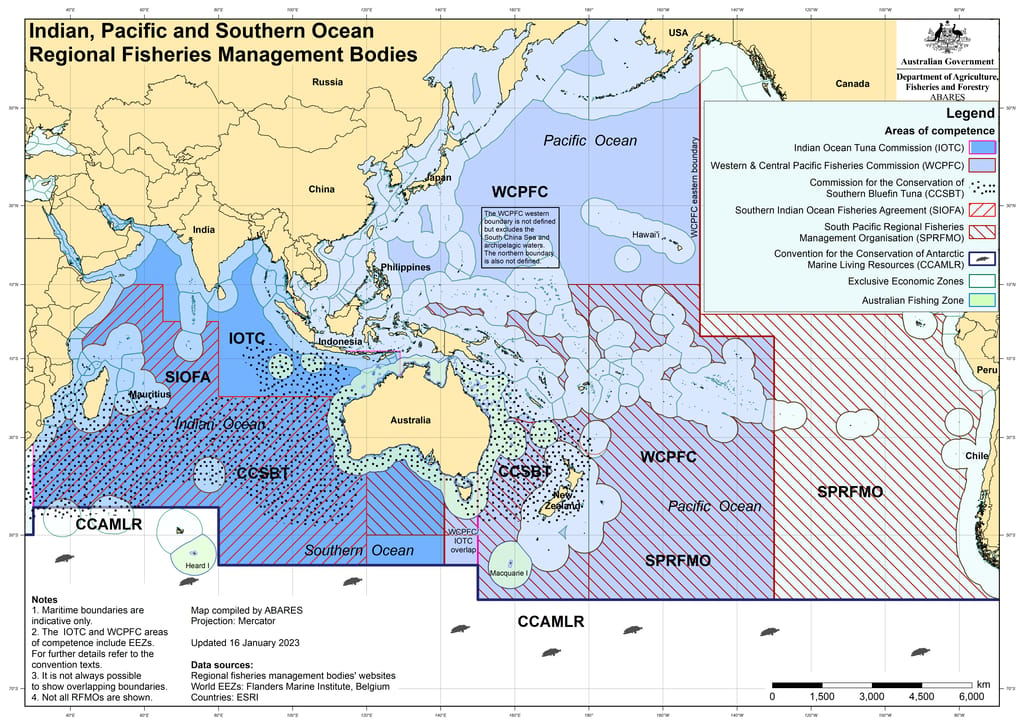

Australia has the world’s third largest exclusive economic zone, sitting across the Pacific, Southern and Indian Oceans, and participates in different regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs). Now is the time for Australia to take the opportunity to refresh and renew efforts to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU fishing).

“There is so much at stake. It is not just about saving the fish stocks, it is about far more than that now: from the integrity of our own maritime borders to the integrity of the order that our foreign policy prioritises so much.”

— AP4D consultations, March 2023

IUU fishing is not only about global fisheries conservation, but is a vehicle for other illegal activities, including as a tool in grey zone tactics. Australia’s role as an effective partner must be to invest to ensure the continued effectiveness and existence of the international rules-based order. If Australia is unable to support states to defend their rights under the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and if those rights disappear, there are serious ramifications for the international maritime order.

IUU fishing is a priority issue for key regional economic and security organisations. For example, the quadrilateral grouping of Australia, India, Japan and the United States (the Quad) has recently launched a maritime initiative to curb illegal fishing in the Indo-Pacific while the Asia-Pacific Economic Community (APEC) has agreed to a roadmap on combatting IUU fishing. IUU fishing is front and centre of Australia’s engagement with the region.

IUU fishing is not a single country issue and needs cooperative regional mechanisms. Even when there is not a transboundary nature to IUU fishing, such as coastal artisanal fleet fishing, there are lessons to be learnt between countries and the sharing of information is critical. Australia has an important role to play encouraging regional cooperation, using its experience with regional fisheries management organisations. Australia has worked to encourage cooperation between Pacific Islands countries and with other partners through the supporting the Pacific Regional Monitoring Control and Surveillance Strategy (RMCS). Australia has also been an active participant in the Regional Plan of Action to Promote Responsible Fishing Practices including combating IUU fishing in the Region (RPOA-IUU). Australia can use its position to share lessons learnt from the Pacific region – and the success it has had in dealing with many of its IUU fishing challenges – with the Indian Ocean region and some parts of Southeast Asia, where capacity building is needed.

The term IUU fishing no longer adequately captures the broad range of challenges associated with sustainable fisheries cooperation. IUU fishing encompasses a range of different issues:

- It can be a result of artisanal and small-scale subsistence fishers looking for a source of food, income and livelihood and going where they need to go;

- IUU fishing can involve commercial fishers working in domestic waters, industrialised fishing vessels and distant-waters fleets working in the high seas acting outside the legal framework in order to make extra money (where organised crime is part of the business model for operations by syndicates not supported by a state, or illegal activity aided and abetted by state actors);

- IUU fishing can involve non-reporting, misreporting or under-reporting and lack of traceability and catch documentation; and

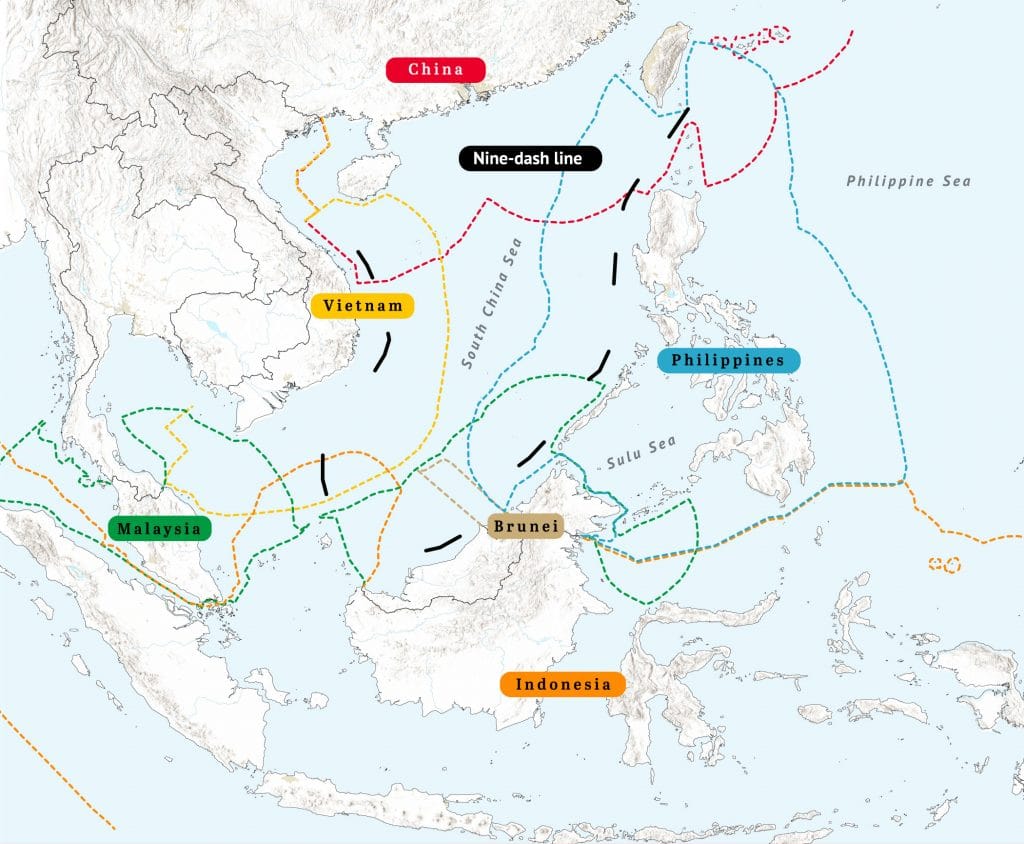

- IUU fishing can be a consequence of unsettled maritime boundaries and maritime disputes.

Each has different drivers requiring different approaches and there is not one solution, meaning that responses need to be multifaceted.

Fisheries are significant renewable resources for Indian Ocean, Southeast Asian and Pacific Island countries. They underpin food supplies and assist economic growth. IUU fishing has a direct social impact and threatens fish stock sustainability, marine biodiversity and habitats, food security, revenue and livelihoods, and regional stability. IUU fishing threatens the harvest of fish stocks both within and beyond the Australian Fishing Zone, impacting fishing industries and communities in Australia and in neighbouring countries. This is a direct threat to Australia. Good fisheries management enables countries to sustainably manage their own resources, and is therefore essential to the viability and future of many of Australia’s neighbouring states.

IUU fishing can become a maritime security issue, exacerbating maritime boundary disputes in Australia’s region. IUU fishing challenges maritime boundaries, damages relations and prevents states cooperating on fisheries management. As a result, fish stocks can continue to decline to the point of collapse. As fisheries collapse and traditional fishing waters no longer provide an adequate catch, fishers may be forced to go further afield including into Australian waters. It is in Australia’s interest to be proactive in managing this to prevent problems in the future that will directly affect Australia.

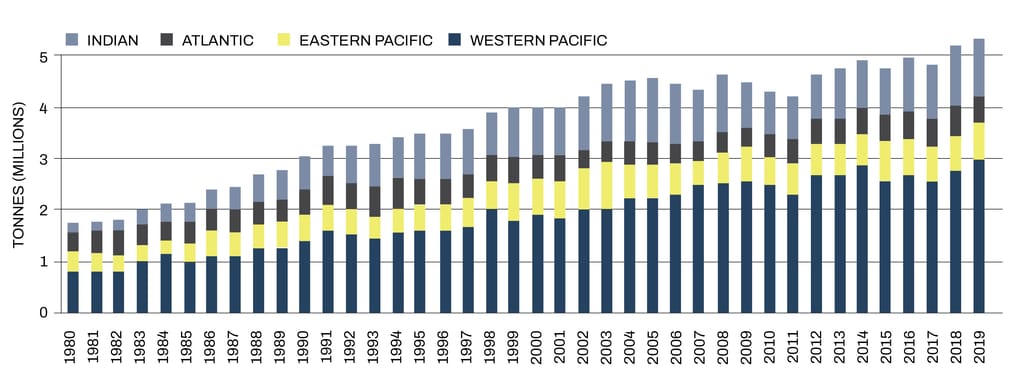

Overfishing threatens marine biodiversity and sustainability of global fish stocks. While overfishing can be legal or illegal, unregulated fishing poses a significant challenge to fishery sustainability and raises substantial equity concerns. Having well-managed, transparent, and accountable fisheries will bring social and economic benefits to communities in Australia’s region. Continuing to build on Australia’s strengths in fisheries management will enhance the performance of regional fisheries bodies and their members.

Climate change, and the conflict associated with it, will impact on IUU fishing. Climate change will impact the abundance and distribution of fisheries, with the most significant declines predicted in the equatorial zone. This zone is home to millions of people whose livelihoods are dependent on seafood. Australia must ensure it is prepared. Understanding the effects of ocean heating is crucial for the future of the world’s fisheries, as well as for conservation strategies to protect marine ecosystems. With declining fish stocks pushing fishing fleets into different areas, including Australian waters, Australia must actively build and support coalitions through bilateral and multilateral engagements and organisations.

Case study: Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR)

The Commission for the Conservation of the Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) was established by international convention in 1982 to conserve Antarctic marine life. The Convention was in response to increasing overexploitation of marine resources in the Southern Ocean, including the increase in unregulated krill catches which was detrimental to marine ecosystems, particularly for seabirds, seals, whales and fish that depend on krill.

CCAMLR’s function is to give effect to the objectives set out in the Convention by formulating, adopting and revising conservation measures on the basis of the scientific research. CCAMLR provides scientific advice on ecosystem monitoring and management; fish stock assessment; statistics, assessments and modelling; and acoustics, survey and analysis methods.

Most importantly, the Commission monitors compliance with conservation measures to ensure fishing is sustainable, and maintains strong market controls to prevent trade in IUU fish.

Australia was significantly involved in negotiating the Convention, and hosts the secretariat and annual meeting of the Commission in Hobart. Australia also led CCAMLR efforts to establish the world’s first high seas Marine Protected Area (MPA), the South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf Marine Protected Area (established 2009), a region covering 94 000 km² in the southern Atlantic Ocean, and the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area, the world’s largest MPA (established in 2016). Australia is again leading the way through co-sponsoring a MPA proposal for the East Antarctica and the Weddell Sea.

CCAMLR is a positive example of what can be achieved when Australia is a strong partner in regional fishing management organisations.

It is in Australia’s national interest to have regulated, rather than unregulated, spaces. IUU fishing avoids a broad range of regulations outside of fisheries and can facilitate transnational organised criminal activities involving humanitarian issues, including human trafficking and forced labour aboard fishing vessels, contraband trafficking (wildlife, weapons and narcotics), avoidance of environmental regulations and criminal laws, corruption and lax border control. There is also potential for fishing vessels to be used as a cover for unauthorised research activities, such as seafloor surveying. IUU fishing undermines the legitimacy of the rules themselves if they can be broken with impunity. Australia has an interest in upholding the international legal framework for fishing as part of defending the integrity of maritime order.

Combatting IUU fishing often focuses on fishing vessels operating at sea, however IUU fishing also relies on low levels of scrutiny onshore. Behind some fishing vessels is a network of companies with complex structures of ownership and shell companies that disguise the beneficial owner. When vessels obscure their ownership, do not operate within a registered fleet or report their true financial gains, their actions undermine legitimate producers and legitimate importers, be it from the smallest fisher to corporations that own vessels that are following the rules.

Limited market controls on Australia’s seafood import industry mean that Australians may be consuming the results of IUU fishing. Australia exports high-quality seafood and imports affordable seafood for domestic consumption. Australia needs to ensure that it is not sourcing seafood from illegitimate sources, undermining legitimate producers. Australia must do more as a nation to improve traceability of imports to support legitimate and sustainable fishing and look to examples such as Japan, the US and the European Union (EU) which are working to improve transparency in the supply chain.

Fisheries management is a whole-of-government issue linking security, trade, foreign policy and development cooperation activities. Its many different elements require coordination across all the tools of statecraft.

Perspectives

Australian perspectives

From a development perspective, IUU fishing is a critical issue as fisheries are central to people’s livelihoods and a valuable source of protein. Australia’s development cooperation program focuses on sustainable development, environmental protection and management, responses to climate change and resilience to natural disasters. As social and climate-related risks increasingly impact small scale fishers, development approaches will need to further social protections to support vulnerable populations whose livelihoods depend on fish.

In some cases the root causes of IUU fishing are poverty-related. This is recognised in Australia’s approach to sustainable fisheries management, outlined in the strategy for Australia’s aid investment in agriculture, fisheries, and water (2015). Where small-scale fishers are coming from poor fishing communities into Australian waters in search of catches, a development perspective is needed. This is highlighted in Australia’s approach to Indonesian traditional fisherman. Small-scale fishers searching for trepang (sea cucumbers) are frequently labelled IUU fishing due to the fragmented and diverse nature of their activities. Yet these are fishing areas that Indonesia traditional fishers have been sailing for hundreds of years. Indonesia and Australia recently signed an agreement to strengthen cooperation in combatting IUU fishing that goes some way in addressing the root causes behind small-scale fishers, setting up a working group to look at alternative livelihoods, alongside traditional law enforcement approaches.

Case Study: Australia – Indonesian Traditional Fishing Agreements

Australia’s co-operation with Indonesia to address the causes and issues of IUU fishing has been mutually beneficial in promoting fisheries and marine cooperation. Australia has established a bilateral agreement with the Indonesian Government whereby traditional Indonesian fishers, using traditional fishing methods only, are permitted to operate in an area of about 50,000km2 of Australian waters in the Timor Sea, known as the MoU Box.

The MoU Box provides access in recognition of the long history of traditional Indonesian fishing in the area. However, rules do apply, and the agreement is limited to Indonesian fishers using traditional fishing equipment and traditional vessels without motors or engines. Some marine species, such as turtles and birds, are protected and there are marine sanctuary zones that have additional rules to protect marine diversity.

This is a good example of what can be achieved when development, defence and diplomacy work together for sustainable fisheries cooperation.

From a defence perspective, the 2016 Defence White Paper states “Over the next 20 years, we expect the threats to our maritime resources and our borders to grow in sophistication and scale. Australian fisheries remain relatively abundant, particularly in the Southern Ocean, making them appealing targets for long-range illegal fishing fleets.”

Australia Defence Force deployment of Australian frigates remains a powerful mechanism for maritime border protection, deterrence and enforcement. Defence intelligence-gathering has been fundamental to addressing unreported fishing and Defence continues to have a significant role to play in security cooperation, as evident by the patrol boats provided under the Pacific Maritime Security Program. There is potential to replicate this successful program in the Indian Ocean to address the significant lack of capacity in the region.

Case study: Pacific Maritime Security Program (PMSP)

The Pacific Maritime Security Program is a comprehensive package of capability, infrastructure, sustainment, training and coordination by the Australian Government designed to increase regional maritime security for Pacific Island nations and Timor-Leste.

The program has three components: the Pacific Patrol Boat Program, aerial surveillance and enhanced regional coordination. Australia is delivering 21 Guardian-class Patrol Boats to 12 Pacific Island nations and Timor-Leste. As part of the program, Australia provides maritime, technical, seamanship, communications and management training courses to crews operating the patrol boats.

The program’s region wide aerial surveillance assists in enhancing regional maritime security and is supported by the Forum Fisheries Agency, which coordinates its implementation on behalf of its members through the Regional Fisheries Surveillance Centre.

The PMSP continues to be a valuable contribution by Australia to regional maritime security. A similar program could be introduced into the Indian Ocean region to support regional engagement to combat IUU fishing.

“Through our Pacific Maritime Boundaries Project, we have long worked to assist Pacific nations secure their maritime boundaries by securing their rightful Exclusive Economic Zones... Access fees paid by foreign fishing vessels to Pacific Island Countries amount to around USD$350 million each year, but could be as much as 40 per cent higher if IUU fishing were eliminated.”

— Ewen McDonald, Head of the Office of the Pacific, 7 June 2019

From a diplomacy perspective, the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper highlights the difficult and contested world Australia is operating in, where the “continuing effective management of our own fisheries will depend on the health and sustainability of ecosystems in the wider region.”

The Australian Government’s diplomatic engagement with partners is critical for good fisheries governance, and to build the regions capacity to support sustainable fisheries management and respond to IUU fishing. Australia is a strong partner to regional fisheries management organisations including the Pacific Island Forum Fisheries Agency, and a range of initiatives through the Pacific Community (SPC), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Quad and the Indian Ocean Rim Association. Australia can bring lessons from across these regional fisheries management organisations, facilitate relationships to build bridges and strengthen collaboration across regional networks: for example, to support nations to build capacity to implement international regulations and law of the sea to protect fisheries.

Case Study: Indian Ocean Rim Association

The Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) is an inter-governmental organisation aimed at strengthening regional cooperation and sustainable development within the Indian Ocean region. The Association has 23 Member States and 10 Dialogue Partners. Fisheries management is a priority for the IORA, with the impact of overfishing and climate change accelerating declining fish stocks. IORA member states are focused on a wide range of issues such as seafood safety and quality, post-harvest processing and storage of fisheries and aquaculture products and sustainable management of fisheries resources.

The IORA Fisheries Support Unit (FSU), based in Oman, undertakes some research and capacity building support, however Australia can advocate for expanded cooperation on fisheries management. From using its own experience in sustainably managing its fish resources, to successfully working with organisations such as CCAMLR and FFA, Australia can provide expertise and advocate for strengthening of IORA sustainable fisheries cooperation.

“We will also continue to work to enhance fisheries governance. As demand for fish products grows, current stocks will come under greater pressure, affecting food security, livelihoods and economic development across many regions. Depleted fish stocks in neighbouring regions degrade our own stocks and can motivate illegal fishing in Australian waters. We will continue to work with our partners in regional fisheries management organisations to ensure the long-term sustainability of fisheries resources. We will also tackle illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, and monitor the status of fish stocks to provide industry with certainty over catch limits. We will continue to assist communities in our region, including through our development assistance, to sustainably manage fish stocks and marine ecosystems, and improve aquaculture production.”

— 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper

Regional perspectives

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states consider combatting IUU fishing as one of their top priorities, with ASEAN countries experiencing over $6 billion in economic losses in 2019 from IUU fishing. ASEAN members recognise the importance of being able to officially guarantee that products from the region are free from IUU fishing. However, a stronger mandate for existing regional mechanisms is needed and there remains significant challenges in regional coordination.

During AP4D consultations the view was expressed that there is no need for new regional mechanisms, or a new organisation that could detract from already limited resources, with the priority to strengthen existing regional fisheries mechanisms, including the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Centre (SEAFDEC) and ASEAN Fisheries Consultative Forum. This would provide a mandate for better management and sustainable development of fish stocks.

The concept of ASEAN centrality remains important in combatting IUU fishing in the region, suggesting that Australia should be consultative and encourage Southeast Asian states to develop their own mechanisms to combat IUU fishing.

However there are multiple views within the region, with ASEAN members not uniformly concerned with IUU fishing and the rights of littoral states, suggesting that Australia take a range of approaches including focusing on the most concerned states.

IUU fishing in Southeast Asia includes the use of prohibited fishing gears, landing of fish in unauthorised ports, transhipment at sea and underreporting, misreporting or non-reporting of catch. Challenges in combatting these activities include a lack of understanding by government and regional fisheries management organisations on Monitoring and Control Surveillance (MCS) and law enforcement capabilities. In response to these challenges, the region would benefit from new technology for surveillance and capacity-building support.

Unresolved maritime boundaries disputes remain an issue for sustainable fisheries management in Southeast Asia. Countries can be both the victim and aggressor in such disputes. Governments in the region are heavily subsidising offshore fishing to exert maritime claims, exacerbating IUU fishing and causing diplomatic tensions. It is important to strengthen capacity and regional cooperation in order to manage tension arising from IUU fishing. Measures such as establishing hotlines, memoranda of understanding, exchanging fishery information and sharing experience on addressing IUU fishing could encourage cooperation. China’s increased fishing efforts in the region have galvanised some ASEAN members to increase cooperation on maritime boundary disputes, leading Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines and Vietnam to sign MOUs to strengthen responses to IUU fishing from Chinese fleets – and a recent agreement between Indonesia and Vietnam to resolve under UNCLOS their long-standing differences about maritime boundaries. Australia should encourage these developments and continue to provide expertise on sustainable fisheries management and fisheries science where requested. Australia’s involvement in these areas has so far been viewed very positively by ASEAN member states.

The success of Pacific Island countries through their membership of the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) and the Pacific Community (SPC) to collectively meet the significant challenges of managing fisheries in their vast maritime zones is a leading example of what can be achieved in other regions. Members of the FFA cover a fifth of the world’s exclusive economic zones: 30 million square kilometres with over 50 percent of the world’s tuna harvested from the Western Central Pacific Ocean. There are still issues and challenges, but the Pacific should get credit for what has been accomplished.

Assistance is needed to not only enhance and strengthen regional mechanisms, but support Pacific partners to implement recommendations at the regional and national level. For example, Australia could assist in supporting member countries to fully implement the FFA Regional Monitoring, Control and Surveillance Strategy (RMCSS) strategy. Interagency cooperation at the country level also remains a challenge. FFA is encouraging police, customs and immigration participation in regional cooperation activities, but further work and support is needed.

The Niue Treaty is a multilateral agreement on cooperation between members of the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) on monitoring, control and surveillance. The treaty includes provisions on the exchange of information, plus procedures for cooperation on monitoring, prosecuting and penalising illegal fishing vessels.

The Niue Treaty Subsidiary Agreement (NTSA) is an additional agreement which enhances cooperation in the conduct of fisheries surveillance and law enforcement activities, and cooperation in sharing fisheries data and intelligence. All FFA members except Fiji, Kiribati, PNG and Tokelau are Parties to the NTSA.

Australia was heavily involved in the development of the NTSA, funding a legal officer to assist the drafting process, and providing assistance through supporting FFA to assist Pacific Island Countries for implementation. The NTSA has been pivotal in enhancing active participation in cooperative surveillance and enforcement activities by providing a framework for Parties to share resources and exchange information.

It being 10 years since the NTSA was adopted, Australia could review the framework to see if it is fulfilling its objectives, and whether there are further opportunities to make the agreement more effective, such as being expanded to be used as a basis for cooperation with other actors in the Indo-Pacific, including France and the United States.

Aligning views

There are a range of views on transparency in combatting IUU fishing. While some advocates are interested in pushing for greater transparency, others are concerned that the sensitivities surrounding this issue will undermine collaboration with the region. One approach is for Australia to focus on improving its own transparency through Australian government regulations, in order to be a global leader. For example, Australia can improve transparency and tracking of the beneficial owner of fishing vessels to ensure corporate and tax loopholes are not exploited. Australia is currently looking at implementing a beneficial ownership register to align Australia with international approaches to transparency of beneficial ownership information. As part of the process a review could be undertaken on Australia’s data collection policies to ensure fishing vessels are not registered to shell companies.

There is a spectrum of views regarding how to address the issue of persons of interest. This is a focus for FFA, however attempts to register and identify people has been challenged by privacy laws in developed countries, including Australia. There has been discussion whether the Niue Treaty Subsidiary Agreement, a multilateral surveillance and enforcement agreement allowing specific countries to agree to conduct operations together, should allow for further sharing of information, on persons of interest, between Parties. From the Australian perspective, there are concerns around collecting and sharing data on people as personal information is viewed differently than vessel information.

The fundamental nature of IUU fishing requires cooperation to be effective. To continue strong and collaborative partnerships, the Australian Government can look to strengthen memoranda of understanding with regional organisations such as the Pacific Island Forum Fisheries Agency on the sharing of data. However there are already many instruments in place, particularly within the Pacific, to allow for Australia and partners to work together within an established framework, and allow for information-sharing on a project basis and upon request by a partner government.

Australia must be responsive to the needs of partners on a case by case basis, to support them to not only collect data but to use it effectively. This would demonstrate Australia working closely and listening to the concerns and priorities of partners, supporting regional priorities on persons of interest and risk profiling while being sensitive to concerns regarding open-source intelligence.

Coastal states can consider a range of policy options to maximise the effectiveness of their jurisdiction to address IUU fishing. For example, ‘fishing’ and ‘fishing vessels’ can be defined broadly, using licence/access conditions to regulate for policy objectives including labour standards, and apply appropriate regulations to unlicensed vessels in transit through EEZ to minimise both the opportunities for IUU fishing and the amount of surveillance required.

Australia’s engagement with partners on such issues provides mutual benefits. Not only is Australia working to share its expertise where needed, through cooperation with partners Australia is also learning how it can improve its own systems.

“Strength through cooperation is the key factor for the success of FFA.”

— Dr Tupou-Roosen, Director General, Forum Fisheries Agency

Case Study: Pacific Fusion Centre

The Pacific Fusion Centre is a newly established centre based in Vanuatu that intends to deliver training and strategic analysis against security priorities identified by Pacific Island Forum Leaders in the 2018 Boe Declaration on Regional Security. Under the guidance of the Pacific Islands Forum Sub-committee on Regional Security, the Centre provides assessments and advice on Pacific regional security challenges, including climate security, human security, environmental and resource security, transnational crime, and cyber security.

The Pacific Fusion Centre will host security analysts from across the Pacific for capacity building and information sharing and cooperation activities. The first cohort of seconded analysts joined the Centre in Port Vila in 2022, spending up to six months producing strategic assessments. They received training and mentoring opportunities to enhance their analytical assessment skills before returning to their home countries.

Barriers and Challenges

Australian fisheries assistance is in demand in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, but IUU fishing does not fit neatly under a single arm of statecraft, making it difficult for partners to access support. IUU fishing impacts ecosystems, economies, human security, international law, governance and human development. IUU fishing can lead very quickly into grey zone activities involving maritime militia. The term IUU fishing, encompassing a wide range of issues, impacts the ability to implement a solution when the problem is not consistently described by all stakeholders. Australia must break down silos between different parts of government to ensure all arms of statecraft are engaged and coordinated in responding to the range of challenges.

Underreporting is one of the most challenging issues for addressing IUU fishing. Without data and information, Australia cannot respond effectively. The challenge of underreporting and misreporting originates from fishers that are non-compliant with reporting systems. There is a spectrum of views on how to tackle this challenge. Significant work is already underway to build on existing monitoring mechanisms such as observers, emerging technology, checks through electronic reporting to facilitate timely data collection, electronic monitoring to utilise sensors and camera technology to verify fishing together with in-port inspections. However, there are cost barriers with existing verification systems. Human observers are seen as important but there are concerns about their safety, as they were originally intended for scientific purposes rather than for monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS). Some view military involvement as too costly and ineffective in covering large areas of ocean. New approaches can be explored that integrate technology and artificial intelligence. Robotic systems can be relatively anonymous and made in large numbers at lower cost than traditional methods.

Others see traditional naval forces as vital for deterrence with no way of replacing patrol boats’ effectiveness in monitoring a country’s exclusive economic zone. Unreported fishing is a good example of this, as ships get away with not reporting their catches through a variety of means, including ship-to-ship transfers at sea and exploiting ineffective reporting requirements in ports. Interstate cooperation and the building of state capacity are a part of the solution, however a physical presence out on the water is still seen as a necessity.

IUU fishing challenges vary from country to country: for example, whether it is commercial or small scale or whether challenges are more in regulation or in monitoring. There is a large range in countries’ e-reporting capacity, with some reluctant to implement regional recommendations. Southeast Asia has a very uneven maritime law enforcement capacity with countries such as Indonesia responsible for a significant maritime boundary area. Australia needs to be conscious of the different needs of each partner, and ensure this drives dialogue and informs Australia’s response.

Civil society and research organisations are important contributors to the work against IUU fishing, supporting governments’ IUU fishing response. Non-government organisations (NGOs) taking a data-centric approach can offer analytical solutions that are novel and at scale, and help to address the issue of monitoring large areas of ocean. However, NGOs do not have access to the range of data available to government. Commercial satellite imagery and Automatic Identification System (AIS) have limitations. Satellite imagery is expensive and requires scheduling which limits its use by NGOs, while governments are also often unable to fully evaluate and utilise all the information collected. Increasing access to a wider range of open-source data will go a significant way in supporting efforts to combat IUU fishing, providing opportunities for NGOs to offer expertise and add value.

Where a significant source of income stems from the sale of fishing rights and licences, states are vulnerable to corruption. Political pressure can be applied from fishing fleets with large financial resources or subsidies. Organised criminals take advantage of weak governance and absent law enforcement at port and sea borders. Large fishing companies can put pressure on small countries with few other revenue options to licence inappropriate and unsustainable industrial-scale fishing, which has pernicious results and undermines the ability to fish in a sustainable and environmentally responsible way.

Australia should ensure vulnerable states are able to adopt the latest scientific methods to prevent overfishing, and have the necessary skills and budget to adequately undertake research into fish stocks, including reliable data collection to ensure access to accurate fishing records.

Southeast Asia represents 12 percent of the world’s catch but 50 percent of global fishing capacity is operating in the region. This is because governments heavily subsidise the fishing industry, allowing fishers to catch more and more of a dwindling stock. The Catch Per Unit Effort (CPUE) varies significantly across the region, with some fisheries remaining sustainable, others dropping rapidly, and some that are no longer economically feasible. Subsidies, which are heavily slanted towards industrial fisheries, mean the industry continues. Australia has a role in promoting best practice for industry-wide subsidies and should ensure it does all it can to eliminate similar mechanisms domestically.

China remains a significant driver of IUU fishing in the region. Unilateral actions taken by China to control areas of the South China Sea and its attempts to stoke divisions between ASEAN’s littoral and non-littoral members (the latter with fewer interests at risk) are factors in preventing multilateral cooperation on IUU fishing. The 2019 IUU Fishing Index listed China as the biggest offender followed closely by Taiwan, Vietnam, Myanmar and Russia. The issue has been further complicated by fishing militia that intimidate fishing vessels from other nations, with other states unable to respond. The situation in the South China Sea will continue to inhibit attempts at regional cooperation in fisheries management. With ASEAN littoral states focused on trying to cooperate on their own disputes to better combat IUU fishing, there is an opportunity to provide resources, where requested, to support regional efforts.

The current Regional Plan of Action for IUU (RPOA-IUU) is viewed as being underutilised and underfunded, with the secretariat running only irregular workshops on IUU fishing. There is an opportunity for the Regional Plan to be significantly strengthened to increase its impact and effectiveness.

The dynamic nature of IUU fishing, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, can be both positive and negative. COVID-19 changed fleet dynamics and operational behaviour, disrupting the operations of Regional Fisheries Management Organisations because of reduced monitoring, control and surveillance capacity due to limitations imposed on the operations of observer and surveillance programmes and the challenges of decision making in virtual meetings. However, the pandemic did encourage the adoption of new technology such as virtual meetings and monitoring of fishing activities.

Australia and Indonesia were instrumental in establishing the RPOA-IUU, a ministerial initiative between eight ASEAN member states, Timor-Leste, PNG and Australia. The aim of the RPOA-IUU is to enhance and strengthen fisheries management in the region and promote the adoption of responsible fishing practices.

The RPOA-IUU Secretariat, hosted by Indonesia, facilitates technical working group meetings to share best practice for responsible fisheries management. In 2022 RPOA-IUU held a workshop on Advancing Regional Standards for Responsible Fisheries to Combat IUU Fishing for members.

The Australian Government’s support for the RPOA-IUU demonstrates a commitment to multilateral processes. However, the RPOA-IUU could be better utilised and there is potential for the RPOA-IUU to do more in the region if supported through stronger member country engagement.

The Vision in Practice

What does it look like for Australia to be an Effective Partner in Combatting Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated fishing

Australia is recognised as a global leader in sustainable fisheries management across multiple dimensions including fisheries science, management and addressing global drivers of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing that impact the Asia-Pacific region. Significant regional engagement in fisheries management has given Australia a great record and strong relationships in fisheries management. It is an area where Australia aspires to be a global leader.

Australia recognises that it has much to offer regionally and globally, including its expertise and experience in fisheries science and management – such as quota systems and maximising value – in marine protected areas, and in information management. Australia sees itself as helping lead dialogue on sustainable fisheries in the region.

Australia is a good global citizen, supporting efforts to strengthen regulation of fisheries at home in order to demonstrate best practice and be a leader in sustainable fisheries management. Australia is focused on improving its import regulations to bring greater transparency and consumer information for seafood imports. Australia seeks to be an exemplar of how to improve transparency in the seafood supply chain.

Australia builds upon its strong record of delivering capacity building across Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Australia has cultivated a good reputation by working with partners, empowering nations through capacity building. Australian Government programs are responsive to the needs of individual countries and work collaboratively to strengthen existing relationships, aligning assistance with partner priorities.

Using all the tools of statecraft effectively, Australia coordinates and breaks down silos across government agencies. Australian fisheries assistance is in demand in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, and close coordination across government will ensure the best outcome for partners.

The Australian Government has a development approach to small scale fishers to promote responsible fishing practices across the region, ensuring a human development lens is applied when combatting IUU fishing. Australia is aligned to Malaysia’s and Indonesia’s approach to small scale fishers, where small traditional fishing operators found in either country’s waters will not be immediately prosecuted but warned and told to leave. Development cooperation assistance is integrated within Australia’s responses to address some of the root causes of IUU fishing including sustainability, climate change, economic livelihoods and education.

Case Study: Australia, Indonesia and Timor-Leste Sustainable Fisheries Cooperation

The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) is providing support to Timor-Leste and Indonesia to develop their fisheries sectors and to increase access to sustainably produced seafood.

ACIAR’s research program for 2021-2022 included a project in Timor-Leste and the East Nusa Tenggara province of Indonesia to identify the livelihood and nutrition benefits of fisheries and test nutrition-sensitive co-management systems for inshore fisheries. The projects sought to use the lessons learned from sustainable inshore fisheries management in Indonesia to guide policy development in Timor-Leste to benefit poor households.

ACIAR’s community-based approach is an example for how fisheries institutions can support remote communities through more community-led infrastructure and skill development. This could be replicated across the region to support small scale fishers.

Australia is active across the Pacific, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, along with its ongoing Southern Ocean responsibilities.

Australia is a strong partner for the Pacific by supporting Pacific-led priorities outlined in regional frameworks including the Regional Monitoring, Control and Surveillance Strategy (RMCSS), and the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent. Pacific priorities for IUU fishing in the region are underreporting, encouraging the use of AIS for safety purposes, addressing persons of interest as a key area, and having a balance between hard deterrence and electronic monitoring and observers.

Australia is focused on providing capacity building assistance to Southeast Asia. Given the range of different capacity levels in the region, Australia tailors its responses to ensure training is driven by country- and regional-level goals.

Australia is strongly engaged in the Indian Ocean at the regional and bilateral level, bringing expertise and knowledge in sustainable fisheries management. Australia also facilitates the sharing of lessons from the Pacific, encouraging Pacific counterparts to engage with Indian Ocean forums.

Australia focuses its attention on the elements of IUU fishing that are the highest priorities in each region. For example, where unreported fishing is the greatest problem – where otherwise legal vessels are working within legal frameworks – the focus is on improving monitoring, reporting and information management plus dealing with regulatory implementation gaps.

Case Study: Shiprider Agreements

Shiprider agreements allow maritime law enforcement officers to observe, board, and search vessels suspected of violating laws or regulations within a designated exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or on the high seas, bypassing lengthy diplomatic approval processes. A Shiprider program also allows officers from one country to board, inspect and operate vessels of another country, permitting a single vessel to patrol both countries’ waters.

In the Pacific, the United States has agreements with Pacific Island countries to allow host-nation enforcement personnel to ride on US Coast Guard vessels and US naval ships in the region. These arrangements leverage the host nation’s authorities and the US fleet’s strength to enforce maritime laws and protect natural resources and the environment, and provide opportunities for capacity building and improved interoperability.

In 2021, Samoa’s maritime security was compromised when the nation’s only patrol boat Nafanua II ran aground. While Samoa awaited a replacement patrol boat, the United States deployed a coast guard vessel to Samoa to conduct bilateral Shiprider operations with the Government of Samoa.

The Niue Treaty Subsidiary Agreement does provide for Shiprider agreements. Australia could lead the way and look at the potential of implementing similar agreements with partners across the region.

Pathways

Deepening and Broadening Partnerships

Australia builds its global engagement and leadership through strengthened engagement in bilateral and multilateral cooperation that supports the Indo-Pacific region.

It should retain its existing areas of focus. Southern Ocean fisheries will continue to increase in global importance because of rising food security challenges and climate change. It is important that management of those fisheries is precise and effective. Australia must remain focused on preventing their collapse by addressing threats to governance in the region, resisting internal and external pressures on increasing resource extraction and increasing catch limits, and making sure inspection regimes are global best practice.

Australia can continue to deepen engagement in the Pacific. The implementation of the Niue Treaty Subsidiary Agreement, which provides a framework for addressing IUU fishing, has been sporadic and it is unclear how much of the framework has been actioned. One area that could be potentially strengthened is on information exchange between fisheries and other law enforcement agencies. This has specifically been provided for in the NSA, but could be expanded to ensure information is being shared between fisheries and non-fisheries organisations.

Australia must also remain engaged in Southeast Asia. It needs to promote its interests as interests of the states in the region, and help them to deal with overfishing, lack of capacity and lack of maritime law enforcement. Australia could create a track 1.5 dialogue involving ASEAN’s littoral states and Quad partners together with fisheries scientists to facilitate cooperation and improve research and capability. This dialogue could also include non-government organisations, bringing together senior officials and influential thinkers to build a shared understanding on the significant challenges IUU fishing presents for governments and peoples.

Australia can broaden its partnerships into the Indian Ocean, where it has had significantly less engagement. Containing vital shipping routes, this region is strategically important to Australia and should be at the forefront of Australia’s IUU fishing engagement policy. Indian Ocean forums such as the Indian Ocean Rim Association are a good place to start, with Australia already having representation and leadership.

Australia could transfer knowledge and expertise gained from working in the Pacific to the Indian Ocean to encourage more coordinated cooperation among Indian Ocean coastal states. Australia has been a key partner for the Pacific and integral in the success of the FFA. The Indian Ocean could benefit from an organisation similar to FFA but tailored to the region.

Case study: Forum Fisheries Agency Regional Monitoring, Control and Surveillance Strategy

Australia is actively engaging with the Forum Fisheries Agency Secretariat and member countries to support implementation of the Forum Fisheries Agency Regional Monitoring, Control and Surveillance Strategy. The Australian development program will provide $2 million from 2022-2024, in addition to Australia’s $5 million per year core funding, to cover additional activities to combat the unreported aspect of IUU fishing. The additional funding has already seen results, supporting FFA members to accelerate the implementation of electronic reporting systems; developing regional electronic monitoring standards; and completing a cost benefit analysis of e-monitoring. Australia is also supporting a review of the strategy and development of a new strategy which will be in place by 2024.

This program demonstrates Australia’s longstanding and ongoing commitment to IUU fishing efforts in the Pacific, and the positive benefits of investment and building strong collaborative partnerships.

Australia can build relationships with like-minded partners to multiply benefits through pursuing trilateral agreements through existing mechanisms such as the Quad and the Partners in the Blue Pacific (PITBP) initiative. Australia can look for opportunities to connect with development partners such as Japan that have implemented programs in support of ASEAN key priorities, including the ASEAN Regional Action Plan for combatting marine debris. Australia must remain engaged in multilateral initiatives, including the Quad and APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation), to ensure initiatives on IUU fishing are fully implemented and produce results. This will require a concerted effort to ensure Australia’s delegations bring expertise from across government, building relationships to develop quality projects that span across political cycles. Australian engagement will not only add legitimacy, but build upon partners’ strengths and bridge weakness. Australia is at an advantage as it doesn’t have the same fishing industry vested interests that many other developed countries have. This means Australia can support positions that other countries cannot.

“Australia used to be very prominent in its interventions in negotiations, and in the positions it took… It would be great to see that anchor re-emerge because they were really admired and justifiably so.”

— Michele Kuruc, Vice President, Oceans Policy, WWFUS

Adopting Best Practice in Australia’s Domestic Regulations

Australia can ensure it is a global leader in sustainable fisheries management by improving transparency in its own domestic seafood supply chain. Australia can look to adopt a system to give consumers the confidence that imported seafood comes from sustainable sources, and incentivise exporting countries to address IUU fishing. Australia could also increase its efforts to prevent seafood fraud (mislabelling) and species substitutions through looking at innovative approaches to testing at its borders. New testing methods such as tamper-proof, high-throughput analyses in hard tissues, together with DNA and biochemical analyses, could play a role in validating seafood origin and support the compliance, enforcement and traceability of seafood products.

Case study: European Union Carding System

The EU system regulating IUU fishing requires states to certify the origin and legality of fish to ensure the full traceability of seafood imported into Europe. The rules are applied to all fishing vessels, under any flag, in all maritime waters.

To ensure imports meet the strict EU fisheries management standards, non-EU countries may be given a formal warning (yellow card) if identified as having inadequate measures in place to prevent IUU fishing. If they fail to improve, they could face being banned (red card) from exporting seafood to EU markets. Given the size of the EU market, potential bans have a big impact and are a significant incentive for countries to address IUU fishing.

The impact of the EU’s card system was demonstrated in 2017 when Vietnam received a yellow card. The resulting extra customs scrutiny pushed fish sales to the EU down by 36% ($320 million) from 2018 to 2020.[1] Australia could consider adopting a similar system to the EU to incentivise countries to address IUU fishing and ensure Australia can confidently supply domestic seafood from legal sources.

Case Study: Japan’s Catch Documentation Scheme (CDS)

Japan, one of the world’s largest importers of fisheries products, enacted legislation in December 2022 to prevent IUU fishing catches entering its seafood supply chain. Japan’s new legislation includes regulation on the Japanese domestic market, and on imported fisheries products.

Japan’s CDS requires catch certificates for four species – squid and cuttlefish, Pacific saury, mackerel, and sardine – when imported into Japan. The catch certificate is issued by the competent authority of flag State of the vessel catching the four species to certify that they were caught legally.

Japan’s CDS, modelled on the EU program, is another example that Australia could use in developing and strengthening its own domestic regulations to support global efforts to prevent IUU fishing.

Australia can work to strengthen its own regulations to improve transparency on beneficial ownership and open-source data, which will be pivotal in pursuing corporations benefiting from IUU fishing. Complex corporate structures enable companies to systematically exploit forced labour and engage in corruption, tax evasion and fraud to make their margins and hide their ultimate beneficial owners. Australia can support best practice by meeting global standards for transparency and exchange of information for tax purposes.

Australia can lead by example in reducing industry subsidies, including the diesel excise rebate scheme, to push industries towards renewable energy. Care is needed that this doesn’t drive perverse outcomes such as crippling the Australian commercial fishing sector, leading to greater reliance on imported seafood products sourced through unsustainable practices.

Continuing to Invest in Capacity-Building

Australia’s capacity-building approach must continue to be informed by research to understand the key drivers of IUU fishing and the needs of partners, and be balanced in bringing expertise, collaboration and learning for both Australia and partner countries. Australia could undertake a capacity needs assessment of partners to support their development in the region, and use this research to develop targeted programs and assist Australia’s understanding of regional IUU fishing issues. Australia can support a regional dialogue on beneficial ownership to discuss how to improve due diligence for coastal countries, and respond with tailored programs. A needs-based approach must also be replicated in the area of technology and AI, already an overcrowded space. Australia’s provision of technology must meet the needs of the recipient in order to not only be effective, but to avoid placing increasing demands on agencies with already limited capacity.

Human resource development will be a key intervention to build sustainable fisheries management expertise. The Australia Awards program is a mechanism already in place that can be utilised for training in fisheries management. The scholarships and short courses offered are welcomed by the region and are in high demand. A ‘Women in Leadership in the Security Sector Short Term Award’ currently offered to Indonesian government agencies including Foreign Affairs, Marine Affairs and Fisheries to share lessons and best practice between Australia and Indonesia, could be extended out to the region with a strong focus on combatting IUU fishing.

The Australian-accredited monitoring control and surveillance (MCS) training course, implemented by the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry in partnership with the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), has targeted capacity building for IUU fishing-related MCS, as well as opportunities for participants to network, share lessons and build relationships. Currently the training is Southeast Asia-focused and offered only to RPOA-IUU members, however this should be extended and tailored to Indian Ocean and Pacific participants.

The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation, together with the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, is currently developing a Legislative Guide on Combatting Crimes in the Fisheries Sector. Once developed, it will be a useful tool to help Australia and partners around Southeast Asia and the Pacific to implement harmonised approaches to IUU fishing and related crimes, including forced labour, money laundering and corruption. Australia could provide training to support partner countries tailor the best practice advice and implement it according to their countries’ legislative needs.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade could design and invest in a major fisheries and marine conservation program for regions of interest – Southeast Asia, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean – bringing projects together into a focused investment with greater coherence.

Longlining had not been used in the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources Convention Area until the late 1980s when fishers started using bottom-set longlines that enabled the deep-water Patagonian toothfish – Dissostichus eleginoides, to be caught in significant quantities. The Commission responded by introducing (in 1991 and 1993) two ground-breaking measures to control what the Commission called “new and exploratory” fisheries to prevent expansion of fisheries faster than the acquisition of information necessary to ensure its sustainable management. CCAMLR set low catch limits accompanied by an intensive research program to establish the basis for a scientific assessment of the stock and its potential sustainable catch limit.

The scientific stock assessments allow CCAMLR to set sustainable catch limits to safeguard the stock and the ecosystem. It does this by aiming to keep the breeding population at 50% of its initial size. This is more precautionary than what is generally accepted, which is normally around 30–40% of initial stock size.

The success of CCAMLR in preventing the illegal fishing of the Patagonian toothfish demonstrates why Australia’s involvement in regional fisheries management matters. CCAMLR’s intervention enabled toothfish fisheries to be developed from an unfished state to a fully sustainably fished state, without becoming overfished or depleted. CCAMLR fisheries management is a model many countries and RFMOs look to in addressing IUU fishing.

Promoting Innovation in Gathering

Open-source information gathering, and the sharing of open-source intelligence around the world will be pivotal in managing fisheries at both the regional and global level. Australia can contribute to developing open-source collection methods and foster greater transparency through implementing a project to map all legislation and regulation that relates to fisheries across the region. This would provide valuable information to partner countries to support training and curriculum development.

Integrating new technology to use in collecting data will be key in combatting underreporting. New technology such as artificial intelligence (AI), when used together with traditional patrols, can support data collection. Companies can be incredibly efficient at collecting data. The New Zealand National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) is already using AI to collect data on a range of marine intelligence. This data is pivotal in being able to prosecute IUU fishing activities. Australia can follow New Zealand’s lead and look to integrate emerging technology in the fight against IUU fishing. Australia can develop a stronger knowledge base by investing in, and using technology such as predictive analytics to forecast IUU fishing. Investing in research and the collection of data will enable further understanding of IUU fishing issues and support informed policy development, and provide opportunities for Australia and partners to build stronger collaborations.

Case study: Starboard Maritime Intelligence

Starboard is a New Zealand subscription-based software company that provides comprehensive data and analysis of maritime activity. By combining global automatic identification system (AIS) data, multiple layers of satellite data, scientific models, and other information and intelligence, Starboard enables subscribers to effectively analyse and investigate vessels and areas on a secure platform.

This cost-effective technology has significant potential as an additional tool in gathering data on fishing vessel activities that is safe and cost effective. It could be used to support governments, border security, NGOs and fisheries organisations to understand maritime activity in certain EEZs. Although not a replacement for traditional enforcement methods, it could form part of Australia’s approach.

Case Study: Electronic Reporting and Monitoring

Electronic reporting (e-reporting) allows fishers to send fisheries information (such as logsheets) electronically over the internet to a database where the information is stored, making reporting quicker and easier.

Electronic monitoring (e-monitoring) uses a system of video cameras and sensors, hydraulic gear sensors, drum sensors, GPS receivers and satellite communications to monitor and record fishing activities. This information can then be viewed independently by fisheries managers and authorities to verify that fishers accurately report the amount and type of fish they catch, and report on interactions with threatened, endangered and protected species.

The benefits of an e-monitoring system include that it is independent, cost effective and safe, as on-board observers are not required. E-monitoring also improves the collection of accurate data, which is vital for successful fisheries management, and supports informed decision making by national and regional fisheries bodies. This technology is vital in combatting unreported fishing through collecting data that accurately reflects fishing activities.

Contributors

Thank you to those who have contributed their thoughts during the development of this paper. Views expressed cannot be attributed to any individuals or organisations involved in the process.

Allan Rahari

Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency

Camille Goodman

Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security

Jade Lindley

University of Western Australia

Jessica Ford

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation

Keith Twyford

Minderoo Foundation

Keith Symington

Minderoo Foundation

Krista Rasmussen

Center for Advanced Defense Studies

Lauren Sung

Center for Advanced Defense Studies

Lily Schlieman

Stimson Centre

Lisa Marie Palma

FACTS Asia

Malinee Smithrithee

Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Centre

Manumatavai Tupou-Roosen

Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency

Michael Fabinyi

University of Technology Sydney

Michael Heazle

Griffith Asia Institute

Phan Xuan Dung

ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute

Michele Kuruc

WWF

Philip Solaris

X-Craft

Quentin Hanich

Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security

Sharon Cowden

Former Australian Federal Police

Tony Press

University of Tasmania

Vu Hai Dang

National University of Singapore

Editors

Melissa Conley Tyler

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons license. You can reprint or republish with attribution.

You can cite this paper as: Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue, What does it look like for Australia to be an Effective Partner in Combatting Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing. (Canberra 2023): www.asiapacific4d.com

Photo on this page: Tom Fisk, Aerial View of Fishing Boats Docked Along The River, used under Creative Commons

This paper is the product of Stage II of ‘Shaping a shared future — deepening Australia’s influence in Southeast Asia and the Pacific’, a program funded by the Australian Civil-Military Centre.

Supported by: