What does it look like for Australia to take...

A Whole-of-Nation Approach to International Policy

Published: February 2024

Executive Summary

Key development, diplomacy and defence policies have called for Australia to take a “whole-of-nation” approach to its engagement with the world.

This moves beyond a “whole-of-government” approach to involve a range of other actors including business and investment, science and technology, education, sports, culture, media and civil society.

At a minimum, a whole-of-nation approach implies that global engagement is not just the domain of core international policy actors but is the role of a far wider constituency.

This push for a more purposefully coordinated Australian statecraft has been driven by an increasingly challenging and complex external environment. There is a sense of having to do more with what we have as Australia’s relative weight in the Indo-Pacific diminishes.

Many of the issues that concern policymakers require whole-of-nation attention, from building a stronger defence industrial base, to the issue of “preparedness” – including social cohesion, security of critical infrastructure and civil mobilisation. These are not issues that can be dealt with by government alone.

“Whole-of-nation” language carries a sense of urgency that Australia’s people, economy, society and public institutions must become more alert to their role in the international sphere and better organise themselves to meet these exceptionally challenging times.

To date, however, there has been little discussion of the substance behind this idea. To go beyond an abstract sense that “whole-of-nation” is a good thing in principle will require an analysis of the perspectives of different actors as well as the barriers and trade-offs in implementing a whole-of-nation approach. This paper starts this process.

Consultations with 113 individuals from 93 organisations revealed broad support for the idea of a whole-of-nation approach. Benefits include:

- increasing effectiveness by harnessing the knowledge and skillsets of the entire country to drive Australia’s international engagement

- leveraging Australia’s assets for maximum influence

- streamlining how Australia conducts its affairs

- making Australia a more consistent, predictable and reliable actor to engage with

- empowering a range of actors by investing in skills, capabilities and opportunities

- helping Australia fulfil its aspiration to play a global leadership role.

Many consulted felt that the scale of international problems such as climate change and geopolitical competition means it is an urgent necessity for Australia to take more of a whole-of-nation approach. Others saw it more as an opportunity to understand and appreciate the range of insights and assets offered by a range of actors in order to harness this activity to drive results.

At the same time, concerns were raised about what a whole-of-nation approach might mean in practice. For example, business and industry bodies noted that there are limits to how much they can be expected to subscribe to a whole-of-nation position given commercial interests; the research sector noted that research and knowledge-building are often most effective when they can pursue discovery without directives; and non-government organisations and civil society groups expressed concern about being expected to subscribe to a single national position.

It is important not to conflate whole-of-nation with homogeneity.

Despite support for a whole-of-nation approach as an ideal, consultations revealed that there are many barriers in practice including:

- the siloed nature of government

- Australia’s federal system

- the diversity of interests and perspectives within the country

- lack of awareness, language barriers and cultural barriers to public engagement in international issues

- convincing sectors beyond government of why it is in their interests to be involved

- the need for new systems, mechanisms and money to support collaboration

- the scale of the aspiration of whole-of-nation to organise and harness the country’s distinct and sometimes competing interests.

The interaction between core international policy actors and other actors with international influence is the crucial interface for a whole-of-nation approach. Recommendations include development of a dedicated domestic policy engagement capability that connects international policy agencies with other federal, state and territory agencies and consistently engages non-government actors such as the tertiary sector, NGOs, community and diaspora groups, media, sports and cultural organisations.

The paper includes examples where cross-sector collaboration on foreign policy are already in action that provide models and lessons that can be replicated in developing a whole-of-nation approach.

A whole-of-nation approach to international policy is not easy. Government resources are not always elastic and permit a new way of doing things. Coordination requires additional resources rather than less. It is not something for governments to latch onto as a substitute for doing things more directly.

This means that taking a whole-of-nation approach to foreign policy is not a simple solution. However, in a difficult world, Australia may have no choice.

Why it Matters

Such statements have not been confined to government policy documents. Opposition figures have used similar language, including Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Birmingham who has noted that economic diplomacy and security are “intrinsically intertwined with successful engagement across cultural, security and other diplomatic domains.”

Similar arguments have been made by military and security leaders. Outgoing Director-General of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service Major General Paul Symon AO has said that: “if we want to preserve [Australian security and prosperity] then it genuinely needs to be some form of whole-of-government, whole-of-nation effort.”

According to Chief of Defence Force General Angus Campbell: “With the boundaries between conflict, coercion and competition becoming increasingly blurred, there is a need today for a greater integration of power [which] involves military power being brought together with other elements of national power – economic, diplomatic, trade, financial, industrial, scientific and informational”.

With this idea entering policy and public consciousness – variously expressed as “whole-of-nation”, “whole-of-society”, “whole-of-country” or “whole-of-Australia” – there is the need to explore the substance that sits behind it.

Employing Whole-of-Nation Language

“The Review calls for genuine whole-of-government coordination of Defence policy and activities with our wider efforts in statecraft”.

“The Review calls for genuine whole-of-government coordination of Defence policy and activities with our wider efforts in statecraft”.

“[Australia should] deploy all elements of our national power in statecraft seeking to shape a region that is open, stable and prosperous: a predictable region, operating by agreed rules, standards and laws, where sovereignty is respected”.

“[A] whole-of-government and whole-of-nation approach to our strategic environment should be adopted”.

“As one of our tools of statecraft, an effective development program is key to building regional resilience. It is in Australia’s national interest to play our part through challenging times.”

“As one of our tools of statecraft, an effective development program is key to building regional resilience. It is in Australia’s national interest to play our part through challenging times.”

“We recognise that Australia’s development program cannot deliver the outcomes we seek in isolation. All elements of our national power must be deployed to respond to the needs of our region—integrating development with our diplomatic, trade, economic, defence, immigration, sporting, cultural, scientific and security efforts.”

“We want this policy and the development finance review to serve as a signpost to Australian institutions and entities operating in the region to guide engagement that supports positive development impact. In recognising just how much our future is tied to the region around us, this should be a whole-of-nation effort.”

“A coordinated ‘whole-of nation’ approach will be key to recognising and capitalising on emerging trends and opportunities.”

“A coordinated ‘whole-of nation’ approach will be key to recognising and capitalising on emerging trends and opportunities.”

“While we have strong people-to-people links, an enduring challenge in both Australia and Southeast Asia is limited familiarity with each other’s economies, societies, business environments and market opportunities. Addressing this challenge will require a whole-of-nation effort across Commonwealth and state and territory governments, universities, the private sector, not-for-profits and communities.”

“Australia will deploy all arms of statecraft to deter and respond to malicious cyber actors”.

“Australia will deploy all arms of statecraft to deter and respond to malicious cyber actors”.

“Cyber is no longer a technical topic but a whole-of-nation effort.”

At a minimum, a whole-of-nation approach implies that global engagement is not just done by a few people working in international affairs but is the role of a far wider constituency. At its most expansive it sees Australia’s “modern national identity” as a crucial source of national power.

It thus moves beyond “whole-of-government” coordination to a wider group of actors.

This means that Australians need to update their mental model of who does foreign policy. Yes, core international policy actors like the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Department of Defence pursue international policy as their core mission. But there are a range of other actors that also interact internationally. These include other federal departments and national institutions as well as state, territory and local governments. And beyond this, many overlapping sectors have international impact, including science and technology, business and investment, education, First Nations, community, civil society, culture, sport and media.

The interaction between core international policy actors and other actors with international influence is the crucial interface for a whole-of-nation approach.

“Whole-of-nation is very much about an ecosystem: a systems-thinking approach that everybody has a role and draws on expertise at different levels and different sectors for different things. Everybody is relevant because we all make the nation work. So, therefore, governments need to know when to say they don’t know enough and bring in other sectors to step up to the plate.”

“If you were to define whole-of-government versus whole-of-nation, you would conceive of whole-of-government to be described as a blurring of portfolio boundaries and creating a degree of lateral accessibility between the different parts of government. Whole-of-nation would almost be the vertical equivalent of that, so creating a degree of accessibility and distillation of complexity amongst tiers down from a federal government approach.”

— from AP4D consultations

“Whole-of-government” versus “whole-of-nation”

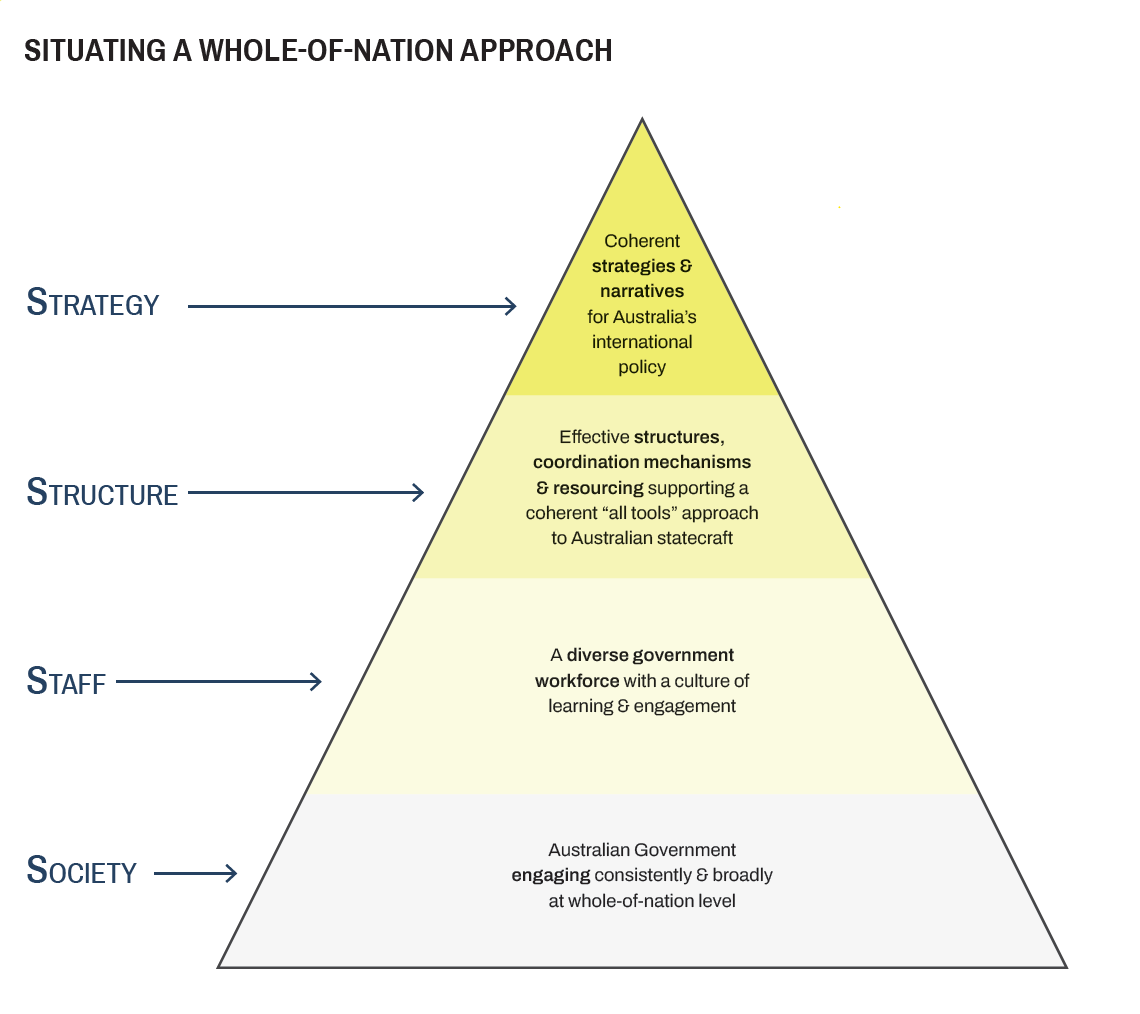

“Whole-of-government” refers to coordination of various elements of government activity to achieve a shared goal. In international policy this includes efforts to provide overarching strategy, establish effective coordination mechanisms and build staff capability to support a coherent “all tools of statecraft” approach across government.

“Whole-of-nation” refers to coordination with tools beyond the immediate control of government. In international policy this involves the Australian Government engaging consistently and broadly with state and territory governments and with non-government actors such as business, the tertiary sector, NGOs, community and diaspora groups, media, sports and cultural organisations.

Adapted from Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue, ‘What does it look like for Australia to use all tools of statecraft in practice’, February 2023.

So why has the “whole-of-nation” idea gained popularity?

This push for a more purposefully coordinated Australian statecraft has been driven by an increasingly challenging and complex external and security environment. There is a pervasive sense of crisis, posed by the complexity of cascading challenges that cut across sectors of society and defy institutional siloing.

To those focused on the climate emergency, it is self-evident that dealing with a problem of this magnitude will require all Australia’s capabilities to be brought to bear in a whole-of-nation fashion. For those concerned about a worsening geopolitical environment, again it is self-evident that a coordinated approach is required. With the Indo-Pacific the epicentre of this century’s great power competition, it is no small matter for Australia to want to contribute to the region’s stability, prosperity and security. This means utilising a range of resources to seek an Indo-Pacific that is peaceful, where international law is respected, where coercion is minimal, and where economies and societies can pursue their own development.

There is also a sense of having to do more with what we have. While Australia will continue to grow in most important respects in absolute terms, its relative weight in the Indo-Pacific is likely to diminish. In a broader global context, a similar shift is likely with relative power moving away from Western countries, including Australia’s traditional allies. In a world where Australia and its allies occupy a less dominant position in the global order, the statecraft of rivals and adversaries becomes more threatening.

In this sense, some use of “all tools of statecraft” and “whole-of-nation” language can be understood in part as a response to what might be called the “total statecraft” challenge posed by totalitarian China. Consistent with the ideology of the Chinese Communist Party, no part of the Chinese state or society is immune from utilisation in a perpetual struggle to secure the party’s security and power.

While it is neither feasible nor desirable for the Australian Government to aspire to such command of its people and resources, some believe the nature and scale of the China challenge compels a more coherent and comprehensive approach by Canberra – to some extent a “top down” approach, albeit with the recognition and maintenance of the asset of Australia’s liberal democracy.

Policymakers are concerned about issues such as the need for a stronger defence industrial base (including better links to industry in general), relatively low research and development in Australia and the general issue of “preparedness” – including social cohesion, security of critical infrastructure and civil mobilisation. Put in these terms, there are many potential positive from a whole-of-nation approach. According to Prime Minister Albanese: “national security demands a whole-of-nation effort. It also presents a whole-of-nation opportunity.”

There is a sense that Australia needs to avoid ‘foreign policy autopilot’. A new breadth of actors and resources and a new depth of coordination and coherence must be injected into Australia’s international and security policy.

“Whole-of-nation” language carries a sense of urgency that Australia’s people, economy, society and public institutions must become more alert to their role in the international sphere and better organise themselves to meet these exceptionally challenging times. This will require that the depth and diversity of Australia’s resources, assets and capabilities — across both the state and civil society — be identified, harnessed and applied to secure our future, in a way that increases their productivity and effective service of Australia’s objectives.

The use of the “whole-of-nation” language implies that current approaches to Australia’s statecraft are insufficient to meet the times. The language can be therefore understood as a call to action to the bureaucracy, private enterprise and civil society to rise to the demands of the times.

From the other direction, a range of actors see an opportunity to improve the quality of Australia’s statecraft by incorporating the views of a diverse set of actors. This could be seen as a more “bottom up” approach.

The next step is to move beyond good intentions and everyone agreeing furiously that this is a good thing in principle. This requires analysis of different perspectives and what the barriers and trade-offs might be in implementing a whole-of-nation approach.

“When we talk about a broader approach to development, it’s a call to arms not just for the rest of government, but the rest of the nation... I want economic institutions, whether it’s through the PALM [Pacific Australia Labour Mobility scheme], whether it’s universities and the higher education sector doing development, and they are partnering with universities in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, I want businesses, I want trade unions, I want churches, I want sporting organisations to think about how they can assist in this area as well, because it should be a whole‑of‑nation effort.”

Perspectives

This paper is the culmination of four months of consultations with 113 individuals from 93 organisations.

Consultations were conducted in multiple ways:

- An online dialogue attended by 73 participants

- Five stakeholder roundtables bringing together senior representatives from Business & Trade, Knowledge & Education, Science & Technology, People & Culture and NGOs & Civil Society

- Two deep-dive group consultation meetings

- Seventeen individual consultation sessions

- Written and oral feedback from AP4D Advisory Group members drawn from multiple sectors.

AP4D is grateful to those who have contributed to the development of this paper. Views expressed here cannot be attributed to any individuals or organisations involved in the process.

A full list of those consulted can be found at the end of the paper.

With so many calls to adopt a “whole-of-nation” approach to international policy, consideration needs to be given to what this would look like in practice. This requires understanding the perspectives of the wide range of non-core international policy actors that would be part of any such approach.

The consultations showed a broadly positive reaction to the ideal of a “whole-of-nation’ approach to international policy. For example, 84% of dialogue attendees responded favourably when polled. Significantly, no respondents said that Australia should not have a “whole-of-nation” approach. This level of support, however, may suggest “whole-of nation” has become something of a “motherhood statement” that sounds good in theory.

Yet there are distinct ideas about how this concept is understood by different actors.

Below we outline the perspectives from different groups, noting whether these sectors broadly perceive a whole-of-nation approach as either a necessity or an opportunity and, in some cases, where they regard the concept with concern.

We also include examples from consultations where cross-sector approaches to foreign policy are already in action. These illustrate the type of collaboration that is possible and provide lessons for developing a whole-of-nation international policy.

Business and Investment

The interests and perspectives of business and industry groups are clearly diverse, so it is impossible to establish a single understanding of their priorities. Yet broadly business and industry see opportunity in strengthening Australia’s modes of international engagement.

A whole-of-nation approach would see the Australian government understand and appreciate the range of insights that can come from the business community. This would involve recognition that businesses often see things that government doesn’t see, and that the relationships and networks formed by business and industry groups can form powerful bonds of mutual interest that can augment Australia’s conventional diplomacy. It is helpful for Canberra to comprehend just how much international engagement occurs outside of the federal government.

“One of the uses of a term like whole-of-nation is for people in the Canberra bubble to remind them how much foreign engagement occurs outside of Canberra. There are so many dynamic community groups and businesses all around Australia that are internationally-engaged and Canberra policymakers would really benefit from a broader understanding of all these assets and networks they might tap into. I think, as a term used to speak to people in Canberra, it’s really useful to help them broaden their thinking. I wonder how much it works when you look at it from the other way.”

“Whole-of-nation is a relationship that acknowledges and values insights and perspectives from outside government to enrich government thinking as it seeks to speak on behalf of the national interest, both internationally, regionally and bilaterally. It is ongoing and dynamic. There is nothing better than effective stakeholder engagement.”

A keener understanding of industry interests and relationships can inform better policymaking, and enhance Australia’s international relationships, particularly in emerging markets where business opportunities can be the primary driver of new cooperation. This can provide signals to the federal government of where it should be focusing its diplomatic resources.

A whole-of-nation approach would assist international partners to understand Australia’s perspective and help Canberra to develop a coherent approach to any specific industry. This approach could balance the interests of states, the federal government and industry groups. It could also build consensus across stakeholders with an awareness of Australia’s strategic priorities and how various industries fit into this wider strategic picture.

Some consultees stressed the value of integrated thinking around national security and economic security. An industry such as mining deeply understands the nexus between its own interests and its impacts on Australia’s foreign policy particularly with key trading partners that Australia is not aligned with. A whole-of-nation approach correlates well with these interests and perspectives. It potentially augments private sector interests with wider government support while enhancing Australia’s strategic interests with a fuller picture of Australian international engagement.

At the same time, some business and industry representatives expressed concern that a whole-of-nation concept could lead to top-down directives from the government about how they conduct their businesses.

There are limitations to the extent that business and industry bodies can be expected to subscribe to a whole-of-nation position given the commercial interests of different sectors. There are incentives that government can create, yet there is a concern that a whole-of-nation approach may lead to government directives over business decision-making.

“When I read the Defence Strategic Review, the sense I got of the way that “whole-of-nation” was being used was more like characterising a war economy, where we’re all expected to pitch in for national security almost to the point where it means that private citizens and businesses are expected to not try and make a profit. And that’s really interesting when we’re not yet at war; we’re not yet directly involved in a conflict. I feel like the troubling bit is this expectation that everybody’s now on a national security footing.”

There has been a shift in economic thinking in recent years and more stakeholders reflect greater acceptance of some government oversight and direction of aspects of international economic activity. A sense of greater necessity means it has become seen as appropriate for government to take the lead in areas that were previously more commercially driven. Big decisions like defence procurement are always going to be government-led, but there’s an emerging recognition of dual use, or in between, categories. In the United States, for example, tech companies are now limited on what they can export to China. These national security calculations may also start to be applicable in Australia within certain sectors, especially in the context of AUKUS’s expectation and obligations.

“There is a really strong sense that it’s not the role of the government to lead when it comes to economic or techno-industrial strategy. That’s quite a cultural issue. It is very different if you went to Northeast Asia, where it’s just assumed that that’s the role that the government will play.”

“We’re in this really interesting place, whereby we need to call for a national approach and we need greater emphasis on security issues, but we also need to be wary of that not meaning that some interests are prioritised, or that the well-being and welfare of some are prioritised over others.”

Business and industry recognise that fragmented approaches are a problem, particularly in key strategic areas. Yet there remains a challenge to incorporate all impacted and interested stakeholders in a whole-of-nation process. This includes businesses and industries that may not yet see themselves as international actors. Part of the whole-of-nation process should be building this awareness.

“It’s about the risk of divergence. It’s about integration. It’s about the risk of actually going in completely different directions. At [our organisation] we cover a huge range of topics which are increasingly geo-strategically of interest, and sometimes we struggle to understand what that whole-of-nation view is. So having a whole-of-nation approach to priority areas would be extremely helpful for us to make sure that we’re pursuing a position… moving in full consensus for Australia.”

Knowledge and Education

Education is an important industry for Australia and a critical arm of how Australia engages with the rest of the world. Consultees saw many opportunities to link the education sector in a whole-of-nation approach.

“Education for a long time has been a core driver of the way that Australia has engaged with the world. From the time of the Colombo Plan in the 1950s and again, with some of the reforms through the 1980s, we saw international education heavily commercialised and it has grown to become our number one top services export.”

Australia does well with education as an export industry and international students provide vital connections to Australia upon returning to their countries of origin. Yet Australia could do more in collaborating on educational initiatives within its neighbourhood and, in particular, cooperating more effectively in science and technology.

A whole-of-nation approach could look at ways to bring together state and federal governments, business and universities to have a shared outward-facing profile. This assists other countries to be able to recognise how they can engage and partner with the university sector, but also the country more broadly.

There is the opportunity to make quality education geared towards both Asia literacy and future skill sets a national ambition. A whole-of-nation approach would see Australia develop a more coherent method to how it develops these capabilities across schools, vocational education and universities, with a keener recognition of how these feed into industry and government.

Central to this would be a better understanding of the importance of Asia and Pacific literacy, and how this relates to Australia’s regional engagement. This neighbourhood literacy also assists with social cohesion and better aligning the country with its current – and emerging – demographics. It helps to correlate Australia’s foreign policy with its internal perspectives and knowledge.

A whole-of-nation approach would have a greater awareness of future industries and the educational pathways that lead to them. It presents an opportunity to identify the industries that Australia will require for the future, how these industries relate to the country’s economic and security interests and environmental responsibilities, and how Australia’s education systems can best facilitate these desired outcomes.

“In terms of education, how do we build the skills for working in a whole-of-nation way, because it requires multidisciplinary and multisectoral thinking and requires engaging in a way that you can hold space for differences… I think that’s where it gets back to education. Are we going to change our system to build those skills?”

Some consultees expressed the view that due to the complex geopolitical environment, it is necessary to have a whole-of-nation approach for education on the skills Australia should develop. This is the basis for an economy that is aligned to the national interest. The Defence Strategic Review highlighted that Australia needs to develop an asymmetric capability and this requires a clear understanding of Australia’s comparative advantages. It also means Australia needs to partner with others internationally, and universities are critical to these partnerships.

“Universities make an absolutely critical contribution. It’s a contribution that is deep, it’s wide, it’s multifaceted, it crosses spatial and temporal boundaries. It brings material and ideational relevance.”

Some consultees expressed a concern that the research sector and research enterprises often bear the unintended consequences of national security measures. There was a perception that the whole-of-nation rhetoric has primarily been concerned with national security. Research and knowledge-building are often most effective when they can pursue discovery without directives. This serves longer-term national interests which may not be immediately apparent in a present-day whole-of-nation vision. Yet the research sector also appreciates how complex national security is and understands that there is a balance that needs to be struck.

“Maybe I’m too cynical but I was thinking about defence and the popularity of the whole of nation language. This could potentially be some people thinking that whole-of-nation would be coming in behind my way of doing things. It’s convenient language in that way since it hasn’t yet been defined. But that’s why this work is really valuable.”

Science and Technology

For science and technology there is the recognition that these sectors impact all aspects of government policy and civil society. The work of organisations like the CSIRO, learned academies, universities and research institutes is critical for both Australia’s domestic and international affairs, and therefore there is an opportunity to contribute to a whole-of-nation approach to policymaking.

Australia has much to offer the world, not only through Western science and technology advancements, but also the deep history with First Nations – some of the earliest technologists in the world who have understandings of the world that are vital to addressing current and future challenges, particularly environmental ones. There could be an important national vision in sharing that history and knowledge as part of Australia’s international engagement.

Australia should be a leader, not a follower, in many areas of science and technology. There is a disconnect between Australia’s research capabilities and what it is commercialising. A whole-of-nation approach can better understand why the country’s research capabilities aren’t being utilised effectively, with the intention of building an innovation economy that matches – or exceeds – Australia’s peers in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

“Australia has so much to give, particularly in science and technology. Such good expertise and we’ve got to try and make the most of it by being an internationally engaged open, positive country.”

“The reality is, we’re so much better if we work well together: if we leverage our strengths and offset our weaknesses and project strength outside of the nation. So, whole-of-nation is an international global outlook that we should make sure that we do well because it’s to the benefit of the whole country.”

Science and technology can be part of an ambitious foreign policy agenda focused on what Australia can offer the world, opening collaborations with new partner countries. Global science and technology networks are incredibly powerful, and experts can be mobilised very quickly. This enables Australian experts to influence innovation throughout the world and be at the forefront of solutions to global problems. This can have considerable diplomatic dividends, particularly in Australia‘s near region.

Pillar II of AUKUS also presents opportunities for Australia to access and advance global best practice on major engineering projects that have multisector applications.

“From the perspective of science and technology, we know that research and development doesn’t happen in a vacuum. We know that an international collaborative approach is necessary, not just in terms of building the knowledge and having access to the knowledge that’s still globally, but also in terms of the potential application of that knowledge.”

“In the science sector I have found it’s more than enough that most of us know each other and that we can work through problems, challenge barriers. I think we’re all sensible people, and we can come to a good outcome.”

Science and technology are at the forefront of Australia’s opportunities within the green transition. Central to this is green energy statecraft, which can help turn Australia’s comparative advantages into competitive advantages. Consultees mentioned the role hydrogen has to play, and the ways that Australia can leverage what it already does well in resource extraction to focus on the critical minerals that are essential to decarbonisation and new energy technologies. This includes not simply being a quarry, but focusing on the processing of critical minerals and the manufacture of technologies they are used in. Australia’s green energy capabilities are essential for enhancing its regional relationships, particularly in the Pacific.

“Australia has an incredible opportunity right now, as we seek to transition to a green economy in a world that is working very hard to address the worst effects of climate change and reverse them if possible, or at least slow and stop them.”

The reality of climate change means there is both a sense of necessity and a sense of urgency, around problems that require scientific and technological solutions. The green transition requires a whole-of-nation approach, and a sense of unity around national objectives and imperatives.

“Climate change requires this type of ‘whole-of-nation’ approach of our systems and our leaders and governments.”

“With this kind of multiple or confluence of macro challenges that we’re facing at this point, it’s critical that we are working together rather than in silos.”

“There’s this growing awareness that crisis is the new norm. What do we do when we have multiple crises, how do we manage that and look for the opportunities at the same time. How do we prepare nationally to be both resilient and opportunistic. If we can think about it in a more sophisticated way, we won’t feel like we’re lurching from thing to thing to thing. Imagine if we had a whole-of-nation approach. Imagine if we had a pandemic and bushfires and another crisis all at once? That is the new normal. We can’t continue in the naivety of thinking it will be one thing at a time.”

The green transition is increasingly a central pillar of Australia’s engagement with its climate vulnerable neighbourhood. The Pacific has a keen interest in building knowledge economies, and Australia should see this as a regional imperative.

“The traditional economic drivers for the Pacific Islands – tourism and fishing – are under threat, and there is the existential threat of climate change; by building a regional STEM workforce we can create mutually beneficial connections that enables us as a region to improve our potential.”

“It’s important to remember it’s not just a challenge, there are also opportunities that are really significant for Australia. This government has a focus on our geographic neighbourhood and there are opportunities there as well. We know that small island Pacific nations are amongst the most vulnerable in the world to the effects of climate change. Science and technology have a part to play there as well.”

In responding to the polycrisis, Australia has some distinct advantages, geographically as well as intellectually – including extraordinary natural resources and a highly educated population. Taking a holistic approach, these solutions cannot be created by scientists or engineers alone, or by the resource sector or governments. There is complexity and nuance that requires understanding and unified efforts across all aspects of national endeavour.

There should be an ambition for the rest of the world to see Australia as a scientifically literate country – good at innovation and developing emerging technologies – that is committed to solving the world’s pressing challenges. Despite Australia’s assets in education and research, there is still progress to be made for Australia to become recognised as a global leader in science and technology, so the pathways to meet this objective need to be identified.

“We know that science and technology is a crucial part of everyday life for every Australian, every person around the world. It’s not just something that is the exclusive preserve of people who are working in labs or working to apply the knowledge that’s created. It’s something that you and I, all of us here use and interact with on a daily basis.”

Civil Society

Instead of foreign policy being seen as a preserve of the federal government, a whole-of-nation approach provides an opportunity for space to be made for other groups to have their voices heard and have access to decision-makers. For example, Track 2 diplomacy enables dialogue to take place at a people-to-people rather than an official level.

Australians see themselves as active in the world, both as individuals and as associations and industry groups that work globally. They are often interested and energetic, but this is not harnessed as effectively as it could be. A whole-of-nation approach can coordinate this activity to drive clear and tangible results, tied to foreign policy strategy and goals.

This requires a shared vision and objectives for what Australia’s international engagement is trying to achieve. From there the opportunity flows to understand skill sets that each sector and civil society group can contribute. This doesn’t mean excluding those who may not meet certain criteria, but instead providing a broad blueprint for organisations to understand and embrace.

“Whole-of-nation means those who often don’t have a voice – lower income, more vulnerable people – having an ability to actually influence government policy.”

“We would always argue at [our NGO] that it’s really important to hear the voices of children and young people in any area of policy significance, and that includes foreign policy.”

There were positive comments that a whole-of-nation approach could help ensure coherence across the multitude of actors operating in the international policy space, particularly in the way priorities are described and entry points to engagement are made accessible and inclusive.

“Whole-of-nation means consistent mechanisms used as tools to engage various bodies, like obvious entry points coming from across key points of engagement and also coherence across a multitude of actors. So common frameworks, common tools that create a default methodology.”

At the same time, the idea of a whole-of-nation approach to international engagement raised concerns for some non-government organisations and civil society groups consulted about the potential of being expected to subscribe to a single national position on every issue.

It is important not to conflate whole-of-nation with homogeneity. Australia should embrace the advantages of being an open liberal democratic society. It is important to recognise and distinguish between national interests and nationalism of the exclusive or aggressive variety.

Another concern expressed was the risk of governments looking to co-opt civil society rather than cooperate with it.

“I think that diversity and inclusiveness of voices also represents ‘whole-of-nation’; we shouldn’t confuse coherence with uniformity.”

“The roles and power of various players need to be able to shift to reflect changing circumstances and objectives, so the system must be geared to this end and, in particular, to afford a wider range of players to input and influence policy development to allow them to be greater stakeholders and provide incentives for collaboration.”

Case Studies

Consultations revealed examples where cross-sector approaches to foreign policy are already in action. These provide models and lessons that can be replicated in developing a whole-of-nation international policy.

COVID-19 VACCINES

The rapid development of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines cut across all sectors of Australian society, connecting organisations within Australia and across the world to meet a national and global emergency. A whole-of-nation approach was implemented creating collaboration across normal commercial competition, with unlikely actors cooperating for the united goal of a vaccine for the world. It brought together networks of scientific collaboration, federal, state and territory governments, business and industry, research, innovation and the community.

COVID-19 highlighted that for Australia to be competitive and have a role in the world it must be internationally engaged. Despite its strong research capabilities, Australia is not a big enough country to have the entirety of the research and innovation necessary to provide for its prosperity in the long term. In science, technology, research and development there is a need for international collaboration to access, build and apply knowledge.

COVID-19 mRNA vaccine development demonstrated that collaboration is the basis for innovation and a foundation for the industries of the future. This approach should be adopted to address the most challenging issues of our time, climate change and the green transition, which will require a holistic coordinated approach to enable opportunities for synergy, innovation, collaboration and creativity.

INVESTED: SOUTHEAST ASIA ECONOMIC STRATEGY TO 2040

Southeast Asia has been one of the fastest-growing global regions, and all its settings – demographics, economic openness, political stability, and ambition – mean it will drive global economic growth through to 2040 and beyond.

Australia’s influence in the region will benefit from stronger economic relationships, and especially more direct investment. The Southeast Asia Economic Strategy is an interesting example of the Australian Government seeking to drive industry to the region, including by helping businesses de-risk potential investment deals.

Australia stands to benefit from, and contribute to, this growth by being a reliable and high-quality supplier of commodities, including agriculture, minerals and energy, and as a provider of first-class services, particularly university education. There are also major opportunities for Australian business in meeting the region’s major infrastructure investment and green energy transition needs.

AUSTRALIAN CENTRE FOR INTERNATIONAL AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH

The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) supports Australia’s agricultural sector to collaborate with international partners on research projects on agribusiness, climate change responses, crops, fisheries, forestry, horticulture, livestock systems, social systems, soil and land management and water.

Funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ACIAR enables the sharing of knowledge and expertise with partner countries facing similar challenges, contributing to poverty reduction by improving productivity and sustainability of agricultural systems and the resilience of food systems. Importantly, collaborative international partnerships built by ACIAR provide opportunities for two-way learning, improving Australia’s scientific capabilities and the productivity and sustainability of agricultural systems in Australia.

NEW COLOMBO PLAN

The New Colombo Plan is an Australian Government scholarship program that supports Australian undergraduates to study in the Indo-Pacific region. The program provides scholarships for up to one year of study, grants for both short and longer-term study, internships, mentorships, practicums and research. Open to Australian undergraduates, the New Colombo Plan supports around 10,000 students each year.

The program is a model for different sectors working together, involving a core international actor – the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade – partnering with universities, business and industry sectors both within Australia and abroad. Students engaged in the program offer an opportunity for public diplomacy as they share Australian culture overseas, while lifting their knowledge of the Indo-Pacific region. The New Colombo Plan Alumni Program supports alumni to maintain connections, deepening Australia’s relationships in the region at the individual and sectoral level.

The scholarship program can become a model for diversification and inclusiveness, key principles underlying a whole-of-nation approach. Scholarships encourage engagement from different sectors of society, including participants from disadvantaged communities that may not traditionally meet eligibility requirements.

BRIDGE SCHOOL PARTNERSHIP PROGRAM

The program, funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and delivered through the Asia Education Foundation, provides professional development programs and reciprocal homestays and school visits.

The BRIDGE program is a model that integrates education, public diplomacy and development assistance to shape the minds and attitudes of the next generation, providing them with the intercultural understanding, real-life digital capability and literacy to become successful and responsible local and global citizens. The program encourages a whole-of-nation mindset and awareness in young people.

Community

Consultations revealed a strong sense of opportunity in a whole-of-nation approach. A number of consultees expressed the view that Australia’s multicultural society is an untapped resource that is not effectively utilised in the country’s foreign policy.

Australia has the world within its own borders, and a whole-of-nation approach would understand the advantages of this. It gives Australia a reach into the world, and a more intimate understanding of each global region that few other countries have. Given the often-competing interests of diaspora groups this can create challenges to shaping foreign policy, but also provides enormous opportunity to present the face of Australia to the world.

A whole-of-nation approach would identify and welcome a variety of individuals and groups into the existing structures of Australia’s international engagement. Pathways to collaboration can often be siloed or exclusive, and this means there are potentially many people whose enthusiasm and perspectives are not being mobilised effectively. This is especially true for diaspora groups. It is important that diaspora groups in Australia feel included as part of the “whole-of-nation” approach.

Australia is a diverse nation, with a positive history of being inclusive, although this can always be improved. The country is capable of bringing together people of different backgrounds and perspectives to engage and collaborate. This is especially important for issues like climate change and within a neighbourhood as diverse as the Indo-Pacific where a process of internal collaboration signals Australia’s ability to collaborate internationally.

“Whole-of-nation involves a recognition that there’s a lot going on in Australia. It’s being inclusive and reflecting who we are and that amazing things are already going on rather than trying to create it. How do you tap into the magic that is Australia in all its diversity and capacity and complexity, but actually amplify that.”

Some consultees expressed the view that Australia needs to be more sophisticated with how it develops skills and utilises its different perspectives and communities. This is necessary for Australia’s cohesion as a nation, but also to address fundamental issues the country faces, as well as transnational concerns. There are always going to be distinct ideas about what is the national interest – and this is healthy – but a broad set of values to guide Australia’s debates about critical challenges is necessary.

It is always in the interests of a country to have decision-makers and civil society in dialogue rather than governments creating policy that the society-at-large must adjust itself to. In terms of social and political cohesion the alignment of civil society and government is not essential but given the array of destabilising forces from climate change to armed conflict there is a duty to find pathways to work in the national interest.

“If you want to get a better outcome, you need to consider the interaction and the relation between different parts of the community and society and you need to address it as whole-of-nation… it’s a best practice approach. If you want to get the best outcome, you need to be holistic.”

First Nations

Consultations suggested that First Nations culture and knowledge is a necessity in international engagement, with an important role for diverse First Nations perspectives.

“In terms of First Nations people that it is important to have a voice in the process, to be a part of what whole-of-nation looks like, because it’s a part of our whole nation, part of our history and our collective culture as well.”

“When we talk about Aboriginal people we tend to in this country to generalise… But in reality, look, we are 250 different nation groups. We’ve got different languages. We’ve got different cultures. We’ve got different governances.”

“If you’re going to start talking about a whole-of-nation approach to international affairs then bring us in. Let us have the conversation. Let’s start with the foundation… start with that respect first and then let’s go from there.”

Some consultees noted that for Indigenous Australians, direct access to international forums has been an important way to project issues onto the international stage and seek support from the international community.

“We’ve still got, you know, the lowest life expectancy rate in the country, but the highest rate of incarcerated people on earth. Nobody brings up these issues… a lack of political empowerment and the ability to control our land and our affairs… For whatever reason these issues don’t get brought up internationally unless we bring them up internationally.”

Some consultees saw that a whole-of-nation approach offers the opportunity to reflect honestly on Australia’s history and identity and look to the future more confident in an inclusive and common idea of what it means to be Australian.

“It is an opportunity for us to take some time to think about who we are as a nation and create our own national identity. Some people think that we have one. As a First Nations person, I think we are still emerging as a modern Australia in what our identity looks like. I see it as a form of nation-building exercise as well as an approach.”

“In terms of the whole-of-nation approach, it’s about viewing that everybody has a role and a place in the ecosystem to build a better society and a global society at that. I very much like future-driven thinking about future generations, that is the core of the focus of future directions. What we choose to do is not about ourselves. It’s about the future of the planet and the future of future generations.”

Some consultees were concerned that a tokenistic approach would undermine any whole-of-nation effort. Respectful engagement with First Nations communities needs to be paired with genuine accountability mechanisms.

“If you want to talk about a whole-of-nation approach, bring Indigenous people into that, and not just in a tokenistic sense… Bring real Indigenous government inside your departments and see what transpires.”

Case Studies

Consultations revealed examples where cross-sector approaches to foreign policy are already in action. These provide models and lessons that can be replicated in developing a whole-of-nation international policy.

COMMUNITY REFUGEE INTEGRATION AND SETTLEMENT PILOT

The $8.6 million program creates a dedicated settlement pathway for refugees referred to Australia by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), where they receive settlement support directly from trained community groups, called Community Supporter Groups (CSGs). The community groups provide support for 12 months from their date of arrival to help settle refugees into life in Australia. The pilot program aims to settle up to 1,500 refugees until 30 June 2025. The University of Queensland is involved in evaluating the effectiveness of CRISP in achieving strong integration outcomes for participants.

The program exemplifies the whole-of-nation approach by involving business, community, education and non-government organisations in an area traditionally reserved for core government agencies. There is greater potential to expand the program, for example by universities sponsoring refugees through education, and business sponsoring refugee visas.

PACIFIC CHURCH PARTNERSHIPS PROGRAM

Churches have traditionally played an important role as drivers of civic values. By focusing on building relationships, the PCPP has successfully created a platform for faith-based organisations to share knowledge, develop relationships and strengthen partnerships. PCPP activities include assistance to Pacific churches to manage the ongoing impacts of COVID-19, and support for learning and cooperation between young and senior church leaders, including through the Pacific Church Partnership Advisory Network (PCPAN) and the Pacific Australian Emerging Leaders’ Summit (PAELS).

With strong indigenous participation, the PCPAN and PAELS also builds on the longstanding cultural and spiritual links between Australian First Nations and Pacific peoples. The program is an example of where the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has provided the mechanisms to encourage non-government actors to participate in Australia’s engagement overseas.

NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR AUSTRALIA-CHINA RELATIONS

The National Foundation for Australia-China Relations is an Australian government initiative to strengthen understanding and engagement between Australia and China, including through empowering communities to build grass roots connections. The national platform works across business, government and communities to strengthen constructive engagement with China by providing practical support and coordinating training and exchange programs.

One example of the foundation’s work is the Beach Smarts for Life program. The program is delivered through partnership with the Royal Lifesaving Society Queensland, Surf Lifesaving Queensland and Jellurgal Aboriginal Cultural Centre, and introduces Chinese international students to Australian surf lifesaving and beach culture. The program focuses on water safety awareness to ensure the beach is a safe space for students to enjoy. The Foundation has also engaged Surf Life Saving NSW to deliver aquatic medical emergency response training to frontline health professionals and first responders in Haikou, China.

State, Territory and Local Governments and National Institutions

State and territory and local governments play a significant role in international engagement, in what is sometimes called “paradiplomacy.” For example, there are about 100 overseas offices run by state and territory governments and in some countries their footprint is bigger than DFAT and Austrade.

This is not a new development. Australian states have been conducting trade policy and going overseas in the name of national interest since before there was a federation. The constitutional debates saw the States strongly reject the idea that the Commonwealth had exclusive control over foreign and trade policy.

“One of the reasons I really like this discussion about a whole-of-nation approach is that it helps us to realise just how much is going on outside of the Parliamentary Triangle in Canberra that is tied to Australia’s engagement with the world… It’s often happening in public, but we’re all blind to it. We just don’t see what’s going on because it’s not at the centre of the common discussion, and you often require a bit of luck to find out about it.”

“It’s a duty. If you have a mandate to build a [national body], you have to engage with the states and territories. You can’t achieve your objectives otherwise.”

Consultees differed in how they saw these links. Some saw them as a potential risk or threat that needs to be regulated, suggesting that the Commonwealth needs to establish some high-threshold red lines about unacceptable behaviour that directly conflicts with national security. Others focused on the need to reduce the risk of divergence, particularly of pursuing unproductive or inconsequential ventures.

It was recognised that the Commonwealth and state and territory governments do not always see eye-to-eye about federalism and constitutional roles. They occupy different political spaces and are accountable to different constituencies: for example, state and territory politicians might not want to be publicly involved if a project is federally-funded.

“There are these ideas that more international links create threats and the potential for exploitation or coercion, but I actually think these are much more of an opportunity – a kind of low-hanging fruit – to support Australian foreign policy and to enable it to become more grounded, more diverse and more creative… We can start to change the way that we think about how Australia approaches the world.”

There is an opportunity to create a whole-of-nation approach through a two-way conversation. Advice from consultees was for the Commonwealth to work to understand what states, territories and local governments are doing and what their goals are; to set up clear lines of communication to demonstrate good faith and manage stakeholder expectations; and to plan for early engagement and involvement in implementation. It was noted that in some cases this will require support, given resource constraints.

“There’s a lot of great work already going on. So some of this effort might be less about creating or establishing and instead merely about identifying and supporting – not trying to replace with single top-down structures, but supporting what’s already there with resources and attention.”

“The reach and networks of states and territories are not taken seriously by the Commonwealth – and they need to be.”

Some consultees expressed a concern that the whole-of-nation approach could, if mismanaged, come to be seen as the Commonwealth paying lip service to the concept, or just conducting a box-ticking exercise, while dictating terms. State, territory and local governments need to feel that they are being taken seriously in terms of their international approach and footprint. Whole-of-nation cannot be about imposing unanimity.

“So if we’re going to make a whole-of-nation approach work then we have to have a foreign policy culture – through government, DFAT, media and in academia as well – that sees a diversity of interests, ideas and information as a real strength. I think there’s a risk that if the concept of whole-of-nation ends up becoming synonymous with unity or synonymous with Canberra’s views, then it will become effectively useless.”

There are a number of national institutions that are deliberately not under government control. These include independent agencies such as the Reserve Bank, Australian Electoral Commission and Human Rights Commission. Such institutions engage in international diplomacy, where their independence is an asset when engaging with counterparts. Consultees noted that they see their work as an integral part of Australia’s diplomacy and that there are missed opportunities where core international actors are not leveraging the relationships formed. Consultees noted that an understanding of national priorities can help inform the work of such bodies to help align with Australia’s broader diplomatic approach and international development agenda. It was noted that it is often difficult to get whole-of-government answer on issues.

“At [our institution] we seek to provide or to offer the international system a unified Australian position. And that can be hard when there’s a lack of direction or leadership.”

“Whole-of-nation is about engaging those groups outside government that do contribute to policy on a domestic or international level. Some are already doing it just not in a structured way.”

Sport, Culture and Media

Consultees spoke about sport as a powerful medium for the international spread of information, reputations and relationships. They saw sport as a way to engage with international partners through sports diplomacy, to show the world who Australia is, what Australia values and what Australia can bring, both on and off the sporting field.

There is a clear opportunity to leverage Australia’s existing deep sporting global networks to advance Australia’s national interest. People-to-people links can be established through sporting competitions and practice. Through media coverage of sport, there is a significant opportunity for Australia to highlight linkages across the globe and to model the values of gender equity, disability inclusion and social cohesion that comes from sharing Australia’s sporting achievements.

The volume of international sports travel by Australians makes it Australia’s largest multilateral global exchange program. Financially, the money spent on global sports and sports broadcasts dwarfs government current expenditure for soft power diplomacy. The size of global audiences for sport and audience levels of interest exceeds any other subject matter, including politics, news, or even traditional entertainment media.

A failure to capitalise in a whole-of-nation way on Australia’s “Green and Gold Decade” of sport would diminish potentially significant cultural, social, diplomatic, economic and strategic dividends. It was suggested that reinvigorating the Sports Diplomacy Advisory Council would be a positive step.

“Australia’s kinship with much of the South Pacific through Rugby Union is a diplomatic asset that other global actors seek… and cannot currently match. Rugby is deeply intertwined with several Pacific nations’ political and military elite…. It tells us that the Australian Government has a wonderful asset to leverage for its international engagement. Australia is currently hosting the FIFA Women’s World Cup, and this sporting mega-event really marks the beginning of what’s been called Australia’s Green and Gold Decade of sport.”

“How we’re perceived on the world stage isn’t necessarily sector-specific, like our experiences in the sports industry. How our image is constructed is also derived from things that the government is doing and things that industry is doing in other sectors. To that extent a unified ‘whole-of-nation’ approach, recognising that actions in one space will have flow on to other spaces, is quite constructive.”

Similar opportunities were identified with arts and cultural industries, including examples of exchanges and leadership courses bringing Australian and Asia arts leaders together to collaborate.

In this sense, a whole-of-nation approach was often seen as a necessity in so far as cultural institutions, sport and media already contribute to Australia’s international policy. A whole-of-nation approach would merely give greater structure and impact to existing practice.

“Sport and media occupy a unique role in this landscape, in that they are – sometimes deliberately, sometimes accidentally – the key amplifiers of the value system or cultural conversation or economic priorities or status of a country. They are two of the key amplification mechanisms for that.”

“The ‘whole-of-nation’ approach is about thinking about our engagement internationally, not just what we consider to be the realm of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the diplomatic space. It’s about the government developing an understanding and a policy and programs about the need for all sectors to engage in a ‘whole-of-nation’ approach and engaging with countries and populations across the globe. The Government needs to promote, and there needs to be a shared understanding and consistency to a degree of what we’re projecting.”

Consultations suggested that the media sector should be seen as a necessary component in a whole-of-nation approach to foreign policy. Australian culture, identity and perspectives are exported across the globe via diverse and diffuse media outlets. Australian agencies engage with international bodies such as the Asia Pacific Broadcasting Union, the European Broadcasting Union and Public Media Alliance, delivering value to Australia’s foreign policy goals.

Within the Indo-Pacific region, Australia stands as one of the exemplars of a political and regulatory system which supports independent public interest media. Independent public interest media is a necessary underpinning of a well-functioning democracy and civil society. It is in this context that support for media development activities (capacity building and journalism training) through development assistance or other funding will support Australia’s foreign policy agenda.

Consultees suggested that a whole-of-nation approach should encourage the government to leverage the Australian taxpayers’ 80-year investment in the ABC’s international services and amplify its ability to reach directly into homes to engage people in the region and to tell the story of Australia.

Media also has the ability to increase Australians’ understanding of other cultures and foster greater international engagement.

“It’s about the Australian people developing a greater literacy about the globe, about a greater literacy about international relations or foreign policy and understanding of our place in the world, about understanding of people, cultures, political systems, particularly in our region.”

“We can bring those stories back to the Australian people and increase the literacy of Australians in the people’s cultures, politics, and issues across the region.”

Similar to other groups, consultees raised the concern that whole-of-nation not be seen as homogeneity or a single voice.

“I don’t know if getting everyone aligned is possible. I think one of the challenges – actually it’s a great strength – is that Australia is a diverse nation. If we’re inclusive that means that we actually have the capacity to bring together people who have different perspectives and hold the space where we can collaborate and engage in our region for important issues.”

“The core international policy actors need to understand that, in fact, they are the facilitators of Australia in the world and not the deliverers of Australia in the world. And that’s not to put the slipper into those particular individuals, but I do think that they need to imagine themselves as the conductors of a broader orchestra, with a wind section and a percussion section. That, really, is the vision that we’re moving towards.”

“We don’t need a single voice. It’s listening to everyone. Everyone’s voices matters.”

Case Studies

Consultations revealed examples where cross-sector approaches to foreign policy are already in action. These provide models and lessons that can be replicated in developing a whole-of-nation international policy.

SPORT DIPLOMACY STRATEGY 2030

The Australian Government’s Sport Diplomacy Strategy 2030 is a good example of a whole-of-nation policy model that maximises Australia’s strengths. The strategy provides a clear plan on how to capitalise on Australia’s sporting engagement on and off the field, benefitting local athletes, sports codes and regional partners.

The strategy acknowledges sport as an important diplomatic asset and empowers Australian athletes to represent Australia globally through encouraging the building of sporting links with our neighbours. The strategy maximises tourism and investment opportunities and strengthens engagement through the Australian-Pacific Sports Linkages Program and Australian Sports Partnerships Program.

The process to develop Sports Diplomacy 2030 exemplified a whole-of-nation participation model, with national consultations undertaken with representatives from all the major Australian sports codes and key sport stakeholders.

The strategy – if sufficiently resourced – will be a framework for Australia to optimise the upcoming ‘Green and Gold Decade’ of sport, as Australia hosts major sporting events over the next 10 years including the Rugby World Cup, Brisbane 2032 Olympic Summer and Paralympic Games and the Netball World Cup. This is also an opportunity to support Pacific sporting aspirations, ensuring the region collectively benefits from global sporting events.

FIFA WOMEN’S WORLD CUP

The 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup is another example of the nation working together to leverage a global event and build Australia’s international profile. Australia used the tournament to engage with international partners through sport, with sectors including media, trade, education, tourism and the private sector benefiting from the event.

The tournament engaged First Nations Kalkadoon artist Chern’ee Sutton to design the branding for the tournament, reflecting an ambition to represent Indigenous culture and history. Business and industry engaged through global partnership deals with FIFA and the knowledge and education sector became involved through universities and think tanks who researched issues impacting women’s sport. The community – including significant diaspora engagement – contributed to the biggest success of the tournament with crowds selling out stadiums and breaking TV viewership records.

INDO-PACIFIC BROADCASTING STRATEGY

The Australian Government’s support for the Indo-Pacific Broadcasting Strategy is an opportunity to strengthen Australia’s media engagement internationally. The 2023-24 Federal Budget significantly increased funding for the strategy to expand media connections, content production and medica capacity training across the region – including $8.5 million to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) to expand transmission infrastructure in the Pacific.

ABC’s dual international media and domestic media distribution role will enable stories to not only be shared with our neighbours, but also provide access to neighbourhood content for Australians. This will enable the ABC to deliver content and services that inform, entertain and educate Australians, including youth, regional audiences and multicultural communities, increasing Australian literacy in the region’s cultures, politics and issues. Boosting media connections enable more Pacific Islands Forum citizens to access to Australian content, creating closer cultural ties to our neighbours.

The Indo-Pacific Broadcasting Strategy will leverage Australia’s strength as a provider of trusted news, and through quality information help keep Australians and its neighbours safe during natural disasters, as well as counter misinformation and support a strong and robust democracy.

Aligning Views

Looking across all the groups consulted, there were some areas of emerging consensus on the potential benefits of a whole-of-nation approach.

First, there was a broad consensus on Australia aspiring to play a leadership role: to demonstrate that in a world of multiple and intersecting crises that Australia is both willing and able to offer solutions. For example, with the green energy transition there is an opportunity for Australia to show greater initiative and vision.

As today’s complex challenges are transnational, a whole-of-nation approach can make Australia a more consistent, predictable and reliable actor to engage with. While Australia already has many intimate and productive international partnerships, there is no ceiling to relationship-building and no limit to areas of international cooperation. For example, assets like Australia’s intelligence capability can complement other channels.

A whole-of-nation approach offers Australia the opportunity to streamline how it conducts its affairs. While there will always be competition between different actors – and this is often healthy – efforts to minimise overlap and duplication and find more complementary modes of operation would enable Australia to be a more efficient international partner across a range of sectors.

A whole-of-nation approach can also increase effectiveness. It can harness the knowledge and skill sets of the entire country to be drivers of Australia’s international engagement, delegating responsibilities to actors whose backgrounds, knowledge and connections can enhance how Australia speaks to the world. It is about understanding the complementary nature of Australia’s strengths and talents.

A key idea in consultations was that of empowerment. Whole-of-nation is about investing in skills, capabilities and opportunities, with a specific focus on raising the country’s Asia and Pacific literacy as a vital tool of statecraft in the coming decades.

It is in the interest of Australia to have its decision-makers in close dialogue with each of the country’s communities and sectors with the ambition of achieving greater political consensus on the larger complex challenges that the country faces. This reflects Australian ideals of a democratic nation-state where policy reflects the sentiment of Australian society. In a highly diverse country such as Australia this can be challenging, but the ability to harness this diversity is an incredible strategic asset.

There was consensus that where Australia currently stands it isn’t going to productively leverage its assets for maximum influence. A whole-of-nation approach would allow Australia to compete more effectively with larger states. It is about a dexterous use of national resources.

Barriers

Consultations suggested that the whole-of-nation concept is seen as more of an aspiration than a reality. For example, while the majority of dialogue attendees said Australia should take a whole-of-nation approach to foreign policy (whatever they defined it to be), 65% believed that Australia did not currently do so.

Several barriers to a whole-of-nation approach were identified.

A whole-of-nation approach is hindered by the siloed nature of government with each department or agency having their own jealously guarded interests. While there are inter-departmental committees and some collaboration mechanisms, foreign policy perspectives are still viewed through different lenses, whether they be development, diplomacy or defence, as well as major interests like trade or emerging challenges like cyber security.

“Actors across the silos, they don’t tend to come together, don’t even have much awareness of the relevance of each other and that there would be benefits engaging.”

“The structure of government and the mechanisms for collaboration can struggle to accommodate issues that have bearing on more than one field of policy. This is unavoidable to some extent given the need for delegation and clear lines of responsibility. The contemporary reality, however, is that almost by default most problems require collaboration across government.”

Australia’s federalism adds another layer of complexity to this problem. State, territory and local governments each have different perspectives and interests that may not neatly align with what Canberra sees as the national interest on any given issue. A win for Australia may not always be a win for a state or territory, or vice versa. Coal mining regions face economic uncertainty from the green transition that needs to be acknowledged and empathised with. These regions may struggle to come onboard with foreign policy objectives like the Pacific Step-Up.

“Engagement with actors outside the Federal Government is ad hoc on international policy, especially with state and territory governments… At the bureaucratic level, there is no consistent strategy or mechanism for harnessing tools of statecraft beyond the immediate control of the Federal Government.”

“Climate change policy is an example of whole-of-nation done badly, with many different and sometimes conflicting interests and opinions. It’s an area where proper net-benefit thinking is really important.”

Lack of awareness also limits a range of actors in taking agency in Australia’s international engagement. Australia’s layers of government requires a high degree of civic literacy. Australia’s compulsory voting creates a good platform of political awareness, but moving upward into issues of foreign affairs there may be less awareness. A durable grounding in civics within Australia’s education systems is therefore vital for a whole-of-nation approach to foreign policy. This is also essential for maintaining trust in institutions and building resilience against misinformation. The fracturing of the media environment makes quality information more difficult to filter from poor information, which in turn makes public conversation and two-way communication more difficult.

“There’s not a lot of understanding of what an Australian whole-of-nation policy might be and that’s an impediment to advancing Australia’s interests in the region.”