What does it look like for Australia to...

Use All Tools of Statecraft in Practice

Published: February 2023

Executive Summary

Australia faces extraordinary challenges to its security and prosperity, all while the government endures a constrained fiscal environment and global economic uncertainty. At the same time, shifting economic, diplomatic and military weight in the Indo-Pacific means that Australia’s influence will decline in relative terms.

This all demands a more coherent and coordinated statecraft from Australia, one that operates most efficiently and is able to do more with relatively less by realising the multiplying effects of various instruments and actors working together in concert. Such an “all tools” approach to statecraft will best position Australia to realise its vision for a region characterised by stability, prosperity, resilience and freedom from coercion.

This starts with a sophisticated understanding of the tools of statecraft, including the sheer breadth of such instruments. Indeed, many of Australia’s most effective instruments exist beyond the conventional domains of diplomacy, development and defence. Government can exercise varying degrees of control over different instruments ranging from complete government control to being a catalyst or influential actor. A sophisticated approach also means recognising that Australia will need to evolve its tools of statecraft over time as the demands on its international policy change.

A more coherent statecraft means that Australian must be able to coordinate its tools and, where necessary, develop fully integrated strategies. This will not only help avoid conflicting efforts but also promote an international policy that brings multiple forces to bear on complex problems. Australia has done this well before, often in urgent crisis situations.

While mechanisms for coordinating Australia’s statecraft already exist, they are insufficient for ensuring that policymaking, decision-making and implementation are consistently and most effectively joined up. There is scope for greater strategic guidance, as well as improved structures and processes at the political and bureaucratic level for running international policy. Other barriers to an effective “all tools” approach to statecraft – such as siloed departmental cultures and impediments to flexible collaboration across government – must also be addressed.

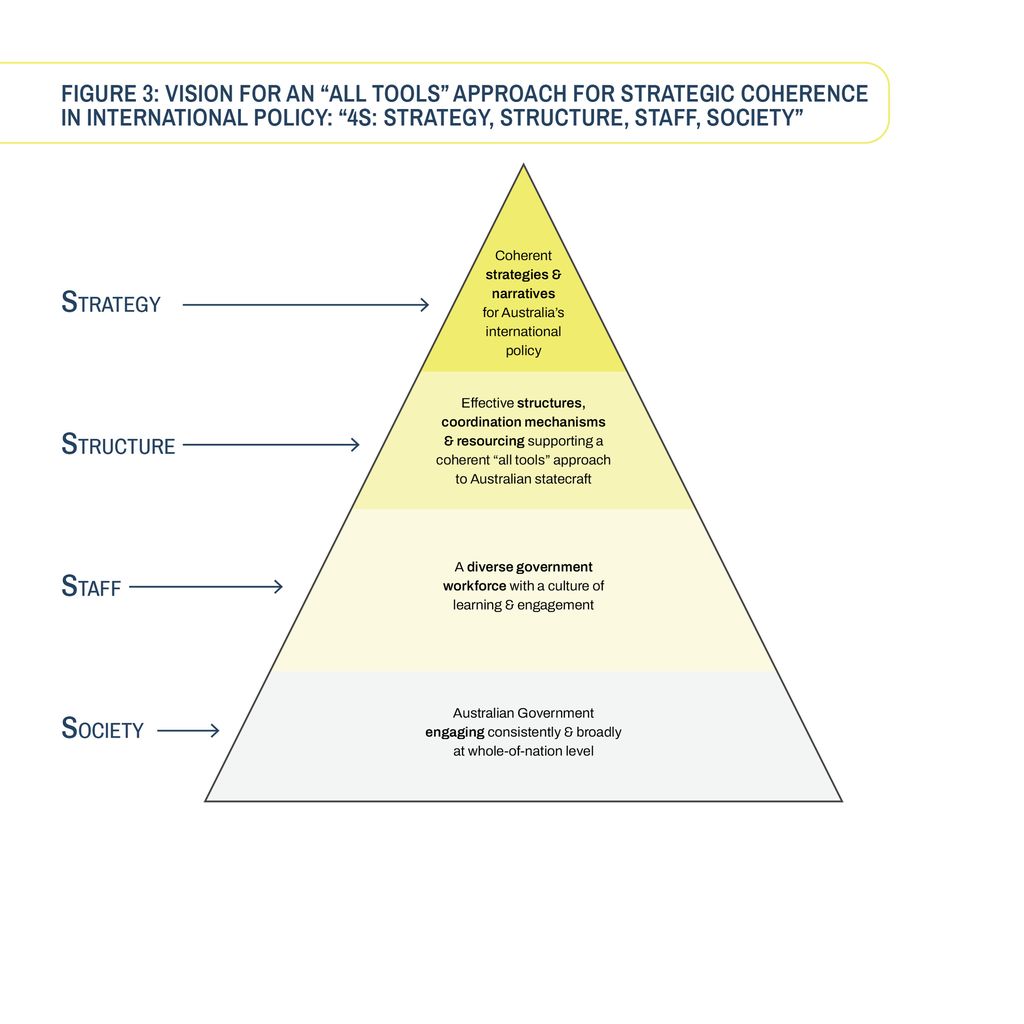

A “4S” set of pathways – strategy, structure, staff, society – is proposed to realise a more coherent “all tools” approach to Australia’s international policy.

STRATEGY: More coherent strategies and narratives for Australia’s international policy

- A coherent strategy and narrative for Australia’s international policy

- High-level political direction about valuing and using Australia’s tools of statecraft

- Greater focus on long-term strategic planning

STRUCTURE: Effective structures, coordination mechanisms and resourcing

- A more inclusive and focused approach by Cabinet and ministers across international policy

- A clearly mandated coordinating entity for international policy

- A more objective approach to resourcing and using tools of statecraft, valuing diverse contributions to Australia’s international objectives

- More collaborative approaches to coordinated planning, policy and implementation

- More streamlined systems for intelligence distribution, information sharing and finding key contacts across government

STAFF: A diverse government workforce with a culture of learning and engagement

- Boost the diversity of professional experience

- Structured engagement and learning opportunities

- A streamlined security clearance system

SOCIETY: Australian Government engaging consistently and broadly at whole-of-nation level

- A concerted effort to achieve whole-of-nation buy-in on international policy

- Develop greater capability to engage external expertise, domestic policy agencies and other actors

Why it matters

Australia’s external environment continues to grow in complexity, driven by a shifting geopolitical landscape and an array of complex economic, environmental and technological challenges – all while the nation faces a relative decline in its national power. To meet the demands of this context, Australia’s international policy needs to fully utilise all of its assets in a coherent and coordinated manner. While Australia is a sophisticated and effective international actor, it is vital to continue to interrogate whether its tools of statecraft and means for coordinating them are fit for purpose.

No single, optimal institutional arrangement exists for Australian statecraft that will fully utilise and perfectly coordinate its various resources and capabilities as circumstances evolve. There is, however, scope for greater coordination between the conventional arms of international policy – development, diplomacy and defence – and to harness broader capabilities, including domestic policy instruments, to advance and safeguard Australia’s interests.

Australia’s statecraft faces an unprecedented mix of external pressures and internal constraints

As power shifts in the Indo-Pacific, Australia’s relative economic, diplomatic and military weight will likely recede – just as the region becomes the centre of geopolitical competition. Australia will remain a significant and influential power, but this power will wane in relative terms as others advance. This will place hard limits on Australia’s capacity for influence and to manage conventional security problems, unconventional threats like disinformation and grey zone tactics, and challenges to democratic and environmental resilience.

Simultaneously, Australia faces extraordinary resource constraints due to the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, budget deficits and ongoing global pressures. A predicted slowdown in economic growth due to high inflation, the ongoing ramifications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the lingering effects of the pandemic together present strong headwinds.

Moreover, problems can no longer be dealt with through institutional silos, especially given the dissolving boundaries between domestic and international policy. The cumulative effect of these pressures and constraints will demand a more efficient and better coordinated approach to statecraft. Australia will need to do more with relatively fewer resources by realising the multiplying effects of combining tools of statecraft effectively. By reducing duplication, ensuring they leverage one another and are better geared towards a select set of aligned goals, Australia will be able to achieve more at a critical time. Moreover, existing mechanisms for coordinating policy are necessary – but not sufficient – for a coherent “all tools” approach to international policy.

Fortunately, Australia has incredible institutional and resource advantages. In combination with astute policymaking and a creative application of all tools of statecraft, Australia can continue to exercise decisive agency over its future and retain regional and global influence.

Boosting Australia’s ability to deliver on the Australia’s agenda for the region

Australia’s partnerships, especially in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, are a central pillar of the Government’s international policy. In particular, there is a focus on valuing regional partnerships in their own right, not simply through the lens of great power competition. The Government’s emerging vision is based on partnering with regional countries and key groupings such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) to realise a future defined by characteristics including: stability, prosperity, resilience, peace, respect for sovereignty, predictability, and freedom from coercion.

The Indo-Pacific faces an array of challenges: climate change and the human security dilemmas created by it; negotiating the challenges and opportunities posed by China’s rapid increase in power; economic recovery post-COVID-19; hybrid threats including disinformation and cyber attacks. Meeting the Government’s expansive vision for Australia’s regional partnerships – despite the cumulative effects of these and other challenges – means developing an approach to statecraft that utilises all of Australia’s assets. The government’s own rhetoric, calling for an “all tools of statecraft” approach to international policy, recognises this imperative. Importantly, this is an area of bipartisan agreement.

Australia’s tools of statecraft

What are the tools of Australian statecraft?

The measure of Australia’s statecraft is how well it can harness, operate and coordinate the sum of the country’s national assets and resources. This starts with understanding what tools of statecraft Australia possesses in order to defend or promote its national interests. A “tool of statecraft” is an instrument or lever through which the government can generate international effects to its advantage.

The below interactive outlines the tools of Australian statecraft and the capabilities and bases of power upon which they rest. “Tools” are articulated here as the specific instruments through which Australia can generate international effects. “Capabilities and assets” are the actors and resources that operate or underlie the tools. The “bases” of Australian national power are the fundamental characteristics and endowments of Australia that are operationalised by the capabilities.

Natural resource abundance (mineral & agricultural)

Favourable natural environment & climate

Australian population (human capital) and favourable demography

Australian continental landmass size & location

Australian history and its history in the world

- Liberal democratic governance & values

- Political stability & social cohesions

- Diplomatic and consular service & assets (DFAT, Austrade, Defence, Home Affairs, others)

- Development institutions & expertise (DFAT, ACIAR, NGOs, contractors, think tanks and universities)

- ADF and Defence people, capabilities & assets

- Intelligence agencies & assets (ASIS, ASIO, ASD, DIO, Home Affairs, AUSTRAC etc.)

- Economic, trade & investment agencies (Treasury, Austrade, EFA)

- Sovereign wealth funds

- Official reserves (gold, foreign currency)

- Domestic healthcare system

- Social security systems

- Fuel reserve

- Financial regulators (ASIC, APRA, etc.)

- Legal advisory & policy agencies (AGD, AGS)

- Law enforcement, border control & prosecuting agencies & assets (AFP, ABF, Home Affairs, CDPP, state & territory police)

- Maritime, fisheries & transport agencies (AMSA, AFMA, CASA, ASA, ATSB)

- Standards setting bodies (Standards Australia, various industry or technical bodies)

- Scientific institutions (CSIRO, ANSTO)

- Immigration system and settlement system

- Independent public institutions (courts, Human Rights Commission, Reserve Bank)

- Domestic public policy infrastructure (other Commonwealth departments & agencies, state & territory governments)

- Knowledge industries

- Extractive industries

- Agricultural industries

- National budget & public spending

- Large and sophisticated consumer markets

- International economic interaction (inward and outward trade, investment, migration)

- Science and technology

- Australian dollar

- Merchant fleet & Australian-based airlines

- Energy infrastructure

- Travel hubs (ports, airports)

- Sophisticated banking and finance institutions

- Defence industry

- Highly sophisticated education system & research ecosystem (pre-school through tertiary)

- Capacity for innovation (social, technological, commercial)

- First Nations people, communities & cultures

- Cultural diversity (including diaspora communities)

- Religious organisations

- Civil society organisations, charities & NGOs

- Trade unions

- Australian media and press

- Think tanks, researchers, educational institutions

- Sport, arts, culture

- Perceptions, history and memory of Australia’s role in the world and particular regions (e.g., historic connection to the Pacific)

Diplomatic engagement with other states

- Bilateral, plurilateral, multilateral

- Across foreign policy, defence, intelligence, security, development, etc

- Making representations, influencing, sharing perspectives, negotiating, coercing

Defence Cooperation programs

Hosting and attending international meetings & ministerial visits

Individual and institutional relationships (political capital)

- Elite networks

- Civil society

- Diaspora relationships

Mediation and conflict resolution as a third party

Consular services

- Provision to Australian citizens

- Provision to other states’ citizens (including hostage diplomacy)

Placement of Australian (or Australian-supported) personnel in international institutions

- Secondment, nomination, campaigning

Economic diplomacy and trade & investment promotion

Engagement and relationships between technical agencies or independent institutions & their international counterparts (e.g., AEC, Federal Court, Human Rights Commission, ACIAR)

Structured exchanges with other states (e.g., parliamentary or youth exchanges, partnerships between universities or think tanks, 1.5 and 2 track dialogues)

Trade, investment & economic agreements

- Bilateral, plurilateral, multilateral agreements

Market access – allowing or denying access to Australian markets for foreign trade & investment (including labour market access)

Development finance

- Direct bilateral finance

- Contributing to multilateral development institutions

Climate finance

Outward investment (FDI & portfolio)

Sanctions

- Targeted at individuals, organisations or states

Tracking, regulating or freezing international financial transactions

Export finance

Domestic market protections

- Subsidies, tariffs, quotas, bans

Tourism (inbound and outbound)

- Encouraging or discouraging Australians travelling to certain destinations

- Promoting Australia as a destination

Funding for international organisations

- Increasing or decreasing funding

Government procurement

- Direct funding (or withdrawing it) for suppliers

- Indirect market-shaping & signalling effect

Loans and grants to individuals, organisations or states (that are not counted as development finance)

Strategic financial inducements

Direct application of physical force against adversaries

- ADF operations

- Offensive or defensive actions

Armed deterrence activity and operations

- Military exercises & international cooperation / coordination

- Force posture decisions

- Capability & procurement decisions

Defence exports

Cyber operations (offensive, defensive, deterrence)

Peacekeeping activities

- Australian-led operations

- Contributing to UN operations

International law enforcement activity & operations (including international cooperation – e.g., INTERPOL, AUSTRAC on illicit finance)

Espionage and covert action (subterfuge, deception, sabotage, disruption, deterrence)

International and multilateral institutions & organisations

- Creating, joining or supporting an international institution

- Degrading or withdrawing from an international institution

Creating or using bilateral and plurilateral architecture

- Diplomatic, defence/security, trade/economic, development, technical

- Alliances, treaties, free trade agreements

- Strategic partnerships, leader/ministerial/officials dialogues, regular meetings of strategic groupings

- Track 1.5/2 dialogues and processes

International law, rules & norms

- Creating, supporting or enforcing rules

- Degrading or abolishing rules

- Litigation (initiating or defending) in international legal tribunals or courts

- Prosecuting individuals in Australia under universal jurisdiction

Legislation and regulation under external affairs power (s 51(xxix) of the Commonwealth Constitution)

Positioning or Australian assets and people overseas (diplomatic missions, development personnel and organisations, ADF personnel)

Direct provision of humanitarian assistance and/or disaster relief

Building physical infrastructure

Development project & programs, including the provision of technical assistance and capacity-building to other nations

Directly providing technical assistance or capacity-building to other nations

Intelligence

- Collecting & using intelligence

- Sharing intelligence with partners or publicly

Disinformation

- Offensive information operations

- Defensive and preventative measures

Free press and media

- International projection of Australian media

- Australians contributing to local media in other countries

- Support for free press internationally

- Mobilisation of counternarratives

- Support for local journalism, civic space, and public accountability in other countries

Role modelling: influencing others through force of example and demonstrated integrity

International education and research

- Scholarships (and other financial incentives) for inbound & outbound study

- International student fees & regulation

- Promoting Australian education internationally

- Support for and regulation of international research collaboration

Strategic communication and messaging

- Speeches & announcements

- Media appearances

- Social media

Cultural diplomacy and promotion

- Conventional public diplomacy

- Amplifying and supporting Australian culture (especially First Nations), society and values

- Grants and foundations for cultural exchange

Advocacy by Australian civil society organisations (independent of government)

Immigration & social cohesion

- Size, composition and origin of migrant intake

- Size and origin of humanitarian intake

- Operation of visa system

- Provision of migrant and settlement services

Domestic economic policy with international effects

- Federal budget (fiscal policy)

- Cash rate (monetary policy)

- Industrial & manufacturing policy

- Industrial relations policy

- Science & innovation policy

- Supply chain assurance

- Anti-dumping policy

Climate change & energy policy

Education & research

- Language learning

- Teaching of Australian history and culture

- Government research priorities and funding

Policy decisions and actions of Australian state and territory governments

Border control (movement of people, quarantine, security screening)

How should we comprehend the tools of Australian statecraft?

The tools of statecraft are not static, but evolve as national capabilities grow and are refined. They can also be strengthened by the manner in which they are utilised. Government can exercise varying degrees of control over different instruments across a spectrum ranging from complete government control (such as official diplomacy or deployment of the Australian Defence Force) to being a catalyst or influential actor (such as in trade). This also affects how quickly a tool of statecraft can be mobilised. It is important for government to be aware of the right role to play and how asserting too much control over certain tools (such as media and culture) can be self-defeating. In a liberal democracy, it is also important that government not overextend its interventions in a manner that stifles or constrains free society.

A sophisticated approach to statecraft recognises that tools can have effects beyond the domain they are conventionally associated with. For instance, security initiatives such as the Five Powers Defence Arrangement or Australia’s Defence Cooperation Program can generate broader diplomatic and development dividends. In a similar vein, diplomacy between foreign ministries can be an important element of conventional deterrence, outlining worldviews and signalling intent. A development cooperation program may deliver on the health and education aspirations of regional partners, thereby becoming not just the language, but also the measure of a successful diplomatic relationship for countries, particularly in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. It is also well understood that trade and investment can benefit from – and be the basis for – deeper relations between countries, whether that be in the diplomatic, security or development realm.

A coherent approach to statecraft allows Australia to recognise the sheer breadth and diversity of instruments available to it. It encourages a creative and flexible approach to international engagement, avoids a reversion to standard operating procedures and allows difficult problems to be addressed through multiple means. All of this encourages a more rigorous approach to policymaking, where all relevant options are considered and evaluated.

In recent times, there has been a perceived overreliance on defence or security instruments as a tool of first resort, in particular at the expense of diplomacy as the default primary response to growing geopolitical tensions. This has also come in response to unpredictable crises: natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic. An overreliance on defence or security instruments may indicate that more appropriate assets are under-resourced or under-prepared. There should be a greater awareness that Australia’s priority regions may view military involvement differently to Australia, especially countries with a history of domestic military use, or no militaries at all like many Pacific nations.

Evolving the tools of statecraft to meet Australia’s needs

As the demands on Australian statecraft evolve, existing tools will need to be adapted or wholly new instruments created. Given that specific capabilities are created by mobilising national resources, often over the long-term, Australia needs to anticipate emergent needs for new tools of statecraft and initiate their development.

This requires the humility to identify global best practices. For example, the limited scope of both Austrade and Export Finance Australia means that Australia does not have the ability to assist Australian businesses find global markets in the way the Export-Import Bank of Japan does.

At a broad level, Australia should continue further developing and investing in different tools of statecraft. This could include:

Continue to prioritise boosting Australia’s diplomatic resources. This could include investing in a greater diplomatic presence and capability outside capital cities in key Asian countries, and developing better relationships with regional leaders beyond established elites.

Resetting the purpose, scope and capabilities of Australia’s development cooperation approach through the new Development Policy which will harness traditional official development assistance alongside whole-of-government capabilities.

Develop a more nuanced approach to soft power, especially knowing how to stimulate the features that make Australia attractive (but which are not directly or entirely controllable by government) – its free media, education system, democratic governance, and lifestyle and clean environment – and developing authentic and subtle ways to promote them.

A greater ability to harness domestic policy tools and recognise their international effects. Immigration and education policy in particular can forge more intimate and resilient international partnerships, as well as better integration with the Indo-Pacific region. For example, as often the first point of contact, complex visa categories with stringent conditions can alienate both elites and the broader public in Asia and the Pacific from visiting Australia. Similarly, Australia’s education system is vital to foreign policy through the circulatory benefits derived from international students, with many government and industry elites in the Indo-Pacific having studied in Australia. Australia developing an Asia-literate population remains vital, including through widespread learning of regional languages.

Australia’s broader public policy infrastructure – across all three levels of government, in universities and think tanks, and in the private sector – is also a valuable asset. These policy capabilities can be utilised to influence international standards in key technical domains and provide public goods to international partners – for instance, Australian expertise in infrastructure, agriculture, public health and public financial management.

Further developing creative and sophisticated tools to counter hybrid and grey zone threats, such as foreign interference.

“Foreign policy must work with other elements of state power to succeed – in this the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.”

— Minister for Foreign Affairs Senator the Hon Penny Wong, 2021

Achieving greater coherence

The importance of coherent international policy

Australia’s international policy can be understood as the iterative process of aligning capabilities with objectives. It is vital, then, that the Government has the means and mechanisms to draw the most out of its capabilities by using them coherently in combination.

Coherence across international policy helps ensure that Australia’s tools of statecraft generate maximum impact. It helps realise the multiplying effects of different actors and instruments acting in concert towards shared objectives. For instance, Australian defence cooperation and development programs working together to bolster the capacity of a partner country to manage its own security. It also helps prevent different elements of Australian statecraft acting at odds with one another. For example, Australia’s immigration policies could undermine bilateral diplomacy, national reputation, and capacity for influence in multilateral human rights forums. Coherence also enables Australia to proactively plan for and shape its region, a perceived shortcoming in engagement with the Pacific in particular.

International perceptions matter too. A coherent approach – where the arms of statecraft act in harmony – demonstrates the discipline and sophistication of Australia’s international policy apparatus.

What does coherence look like?

What it means for tools of statecraft to work together coherently depends on the context and what Australia is seeking to achieve. In some instances, the bare minimum of avoiding conflicting or duplicative effects between different tools is sufficient. In other cases, active coordination is necessary to ensure policy and action are broadly aligned around overarching goals, even while each tool of statecraft operates independently. A fully integrated approach, where policy is developed from first principles and implemented across multiple tools of statecraft, may also be needed in some instances.

The table below sets out these different layers of coherence in international policy. These are not rigid categories: how tools of statecraft work together in practice could adopt various aspects of these layers at different points. However, the distinction between “integration” and “coordination” is important to understand given the implications for how different tools of statecraft work together.

Level of coherence

Characteristics & examples

Integration

Policy development and implementation are fully integrated from first principles across tools of statecraft.

This is the highest degree of coherence, where a unified strategy is centrally developed and implemented, cutting across multiple policy areas and utilising multiple tools of statecraft.

Full integration is difficult. It is intellectually demanding and resource intensive, often requiring a designated whole-of-government entity (e.g., a task force) to manage and implement it. Given this, pursuing a fully integrated approach should be done so selectively.

A full integrated approach is most useful for:

- Developing high-level national strategies and narratives on significant, long-term challenges – e.g., greater power competition, enduring alliances and partnerships, human and environmental security.

- Delivering responses to discrete issues or crises that engage multiple tools of statecraft (see examples in table below).

Full integration can in some cases be counterproductive – e.g., for international development policy to be most effective in a particular place, it may need to take a broader national interest perspective than security policy. Forcing these to be perspectives to be integrated under unified objectives and control could diminish the effectiveness of each individual tool of statecraft.

Coordination

Tools of statecraft operating independently but with policy and action broadly aligned around overarching goals.

Given the need for specialisation and delegated responsibility across government, the tools of statecraft will continue to be “owned” and operated independently by different actors (i.e., DFAT will run most aspects of diplomacy, development and trade; Defence will lead on strategic policy and most dimensions of “hard power”).

Given this, Australian statecraft should aspire to a coordinated approach in most aspects of its international policy. This means ensuring that the various actors (and the tools they use) are broadly aligned around overarching goals, are aware of each other’s role, and regularly communicate to share information, combine resources and coordinate action. Coordination is less intensive than full integration (as above) and recognises that different tools and actors in Australian statecraft each have their own areas of primary responsibility, equities and strengths.

Coordination is an imperative, for example, in bilateral relationships with engagement across a range of actors: foreign ministries, defence forces, development agencies, trade negotiators, and others. Each of these actors in the Australian system should have a shared understanding of Australia’s interests and priorities in the bilateral relationship, and be in constant dialogue with each other.

Avoiding conflict or duplication

Ensuring that tools of statecraft do not act at cross purposes or are duplicative.

At a minimum, Australian statecraft should ensure that different tools and actors do not operate to undermine or duplicate one another.

An example of cross purposes could include a situation in a bilateral relationship where development programs are focused on improving governance and transparency while diplomatic efforts are overly focused on cultivating relationships with elites suspected of corruption.

An example of duplication would be multiple Australian Government agencies providing funding to an institution or program without differentiating the purpose of their separate contributions.

When done well, coherent Australian policy and action should appear seamless – such as in effective crisis responses to the downing of flight MH17 or the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami. It is, however, conspicuous when coherence is lacking – for instance, discontinuity between domestic and foreign policy on climate change. The table below outlines examples of coordination and integration to generate coherence in Australia’s international policy.

Cambodia Peace Settlement

Australia’s role generating an innovative model for peace and governance transition in Cambodia in the early 1990s illustrated the effectiveness of multiple elements of statecraft being brought together to work cooperatively and creatively. International law and governance expertise, defence perspectives, and diplomatic insights were combined through an intensive collaborative process to develop the initial peace proposal – the “Red Book”. In its implementation, Australian military leadership of the international peacekeeping force, Canberra’s strong relationships with Jakarta and Washington, and the provision of development assistance to Cambodia were crucial to the nation’s transition.

Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI)

RAMSI ran from 2003 to 2017 under Australian leadership with the principal aim of restoring law and order in Solomon Islands following its collapse in mid-2003. Led by a Special Coordinator (a senior DFAT officer), at its height RAMSI comprised ten Australian Government agencies and 2,225 personnel – primarily ADF and AFP, as well as people from participating regional partner countries. While the centrepiece of RAMSI was the AFP-led peacekeeping force, ADF capabilities provided force protection and logistics. Diplomatic engagement was key for ongoing political cooperation with the Solomon Island Government and coordination with Pacific partners. Australia’s development capabilities were brought to bear through law and justice, machinery of government, and economic governance programs. RAMSI illustrates the complementing effects of security, diplomatic and development being brought together under a clear structure and leadership.

Creation and structure of the Office of the Pacific (OTP)

The creation of OTP in 2019 represented a new approach to managing and coordinating whole-of-government policy towards a specific geographic region. A new “group” under deputy secretary level leadership was created in DFAT with a mandate to coordinate all government policy and programs with respect to the Pacific and drive overarching strategy. OTP itself manages bilateral and regional engagement, economic and human development, and aspects of security engagement.

It also coordinates – through mechanisms such as secondments, IDCs, cabinet processes and informal engagement – the Pacific-related work of other agencies. These include: Defence, Home Affairs, Finance, Treasury, AFP, Agriculture, Water and the Environment, National Indigenous Australians Agency, Attorney-General’s, Health, Export Finance Australia, and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority. OTP provides a template and testing platform for developing functional bureaucratic structures for coordinating international policy around government priorities. Further progress remains to be done, however, around developing integrated regional and country-level strategies for the Pacific that apply across government.

Operation Sovereign Borders (OSB)

In its tenth year of operations, OSB demonstrates effective collaboration across government within an integrated structure. The core Joint Agency Task Force (JATF) is led by a senior ADF officer and sits in the Home Affairs portfolio under the Minister for Home Affairs. Core JATF operations are led by different agencies: AFP (disruption and deterrence), ADF and Border Force (detection, interception and transfer), and Home Affairs (processing, resettlement and returns). OSB also draws on diplomatic resources (Ambassador for People Smuggling and Human Trafficking), intelligence agencies, and an array of law enforcement capabilities. JATF and OSB demonstrate the importance of a strong political-level mandate and a clear interagency structure to make multiple tools of statecraft act in concert.

The Sandline Affair

In response to the likely use of mercenaries in Bougainville in 1997 by the Government of Papua New Guinea (PNG), Australia leveraged multiple tools of statecraft through its diplomacy to dissuade PNG Prime Minister Julius Chan from proceeding with their deployment. Defence cooperation, bilateral development assistance and relationships with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were all used in a coordinated diplomatic effort as inducements and deterrents to the proposed use of mercenaries. Australia’s close relationships with the UK, US, and New Zealand were harnessed to broaden the diplomatic weight brought to bear. Australia used intelligence assets to monitor the mercenaries’ movements while briefing trusted journalists to increase the public pressure on the PNG Government. Key to Australia’s success in influencing Chan’s decision to terminate the mercenaries’ contract was the leadership and clear objectives laid out by Prime Minister John Howard from the beginning of the crisis, as well as the earlier monitoring and planning of the situation by the Strategic Policy Coordination Group.

Response to the 9/11 terror attacks

Swiftly following the attacks by Al Qaeda on the United States on 11 September 2001, the Australian government moved to activate the ANZUS Treaty and initiate a robust diplomatic program of support for the United States and to defend itself and other nations from further attacks. Meanwhile, a consular response was activated for affected Australians and intelligence assessments were rapidly re-evaluated in collaboration with other Five Eyes and NATO partners. The ADF was mobilised as part of a coalition force to expel Al Qaeda from Afghanistan, and a persistent multi-pronged campaign of covert action using kinetic, digital, financial, and informational means was undertaken to degrade the capacity of Al Qaeda and its capacity to operate. Australia also worked to reset the multilateral regulatory framework around terrorist financing through the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

Realising greater coherence

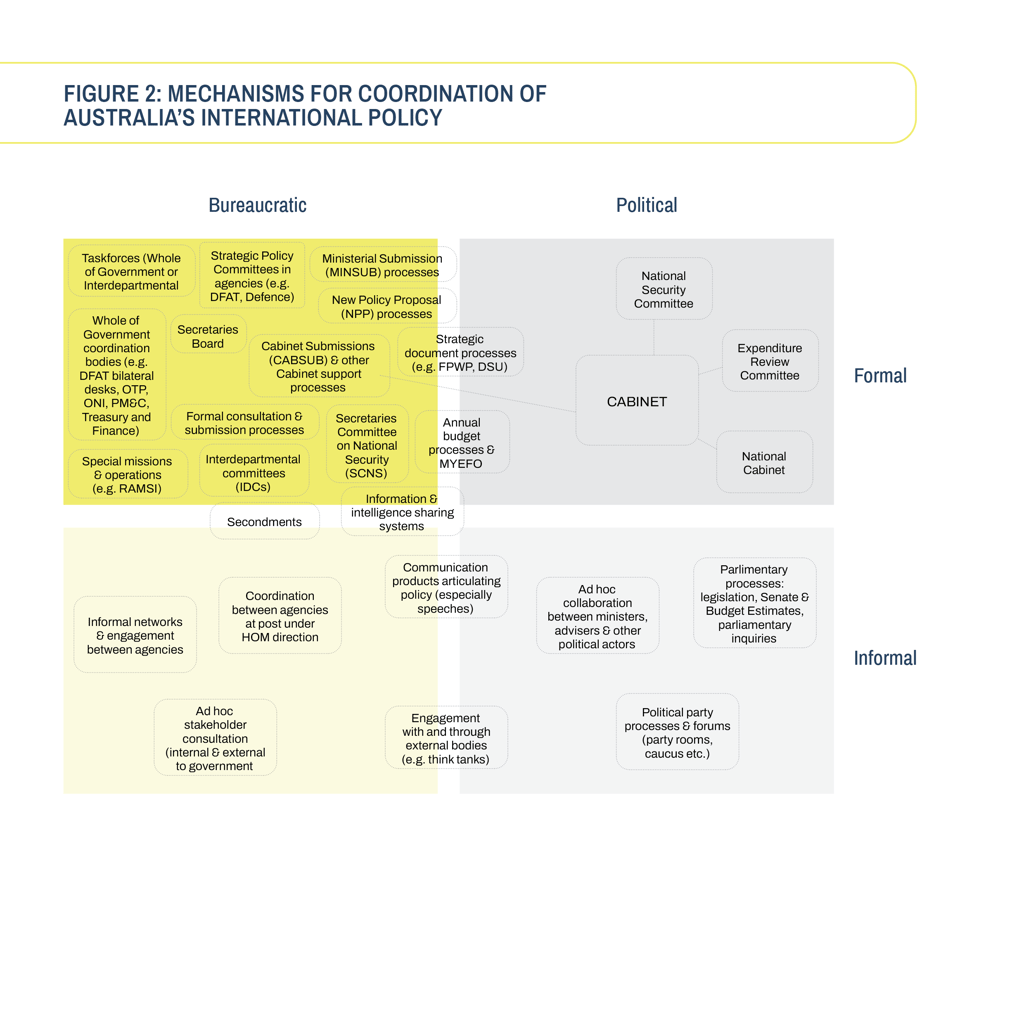

Figure 2 below captures the main mechanisms – both formal and informal – by which international policy can currently be coordinated and implemented across the Australian Government, at both the political and bureaucratic level. Each can serve different purposes in specific contexts across the policy cycle.

Each of these mechanisms can be effective when employed well in an appropriate context. It is clear, however, from the experience of current and former public servants that challenges remain for the Australian Government both in ensuring that the best possible mechanism is used in the right way at any moment and in improving the range of mechanisms available – especially at earlier stages of policy development.

The structure of government and the mechanisms for collaboration can struggle to accommodate issues that have bearing on more than one field of policy. This is unavoidable to some extent given the need for delegation and clear lines of responsibility. The contemporary reality, however, is that almost by default most problems require collaboration across government.

The broadly held view – inside and outside government – is that Australia is generally a highly proficient actor when dealing with discrete issues, especially pressing challenges or crises that compel actors to work together (such as in the RAMSI, Sandline and 9/11 examples above). Effective policy and action is also commonly facilitated by a clear coordinating structure, such as between agencies at overseas posts or within an interdepartmental task force working to well-defined parameters. Operation Sovereign Borders exemplifies this. As the table of examples above show, clarity on objectives and narrative, a strong ministerial mandate, effective leadership by senior bureaucrats, and agencies having a collective interest in an issue are also important factors enabling integrated policy and action.

The challenge for Australia is to achieve similarly positive outcomes at the macro level: consistently coordinating policy and action (and developing fully integrated approaches where needed) over the long-term on the big strategic issues – great power competition, enduring alliances and partnerships, human and environmental security – right across the machinery of government. That requires strategic planning and the execution of coherent strategies in the absence of urgency and where objectives evolve iteratively.

Better mechanisms for coordination and integration

The broad consensus is that the existing mechanisms for coordinating policy are necessary – but not sufficient – for a coherent “all tools” approach to international policy. Conventional bureaucratic processes – such as ministerial and cabinet submissions, interdepartmental committees (IDCs) and new policy proposals (NPPs) – are themselves not effective means for eliciting input and coordinating perspectives and resources because they come too late in the policymaking cycle. Nor should policy only be properly coordinated for the first time by agency heads at the Secretaries Committee on National Security (SCNS) or by ministers at the National Security Committee (NSC). More flexible structures for interdepartmental work that foster continual collaboration right throughout the policy cycle must sit below capstone outputs such as cabinet and ministerial submissions.

The structure and processes of Cabinet committees should be examined. The trade minister is not currently a member of the National Security Committee, meaning trade and investment interests are not directly represented. The powerful Expenditure Review Committee (ERC), which controls government spending, also lacks an explicit structure for considering international policy. Overall, Cabinet processes at the political and bureaucratic level could benefit from review to enhance their capacity for long-term planning and consideration of cross-cutting challenges.

Most obviously, there is no bureaucratic body with the clear authority to develop integrated strategies on the most significant strategic issues and coordinate the application of various tools of Australian statecraft across government (and more broadly with non-government actors). The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) does not have the mandate or resources to perform this role. While DFAT has leadership in areas such as coordinating engagement across government in bilateral relationships, it also does not always have the mandate or resourcing to develop international policy across government or coordinate its implementation.

Engagement with actors outside the Federal Government is ad hoc on international policy, especially with state and territory governments. National Cabinet has not yet evolved to consider international policy explicitly. At the bureaucratic level, there is no consistent strategy or mechanism for harnessing tools of statecraft beyond the immediate control of the Federal Government.

Practical and cultural barriers

While positive strides have been made, the federal bureaucracy remains unnecessarily siloed in its ability to collaborate effectively across government. The core institutions of Australian statecraft – DFAT, Defence, Home Affairs, Treasury, etc. – often adopt different worldviews and understandings of the national interest. While contestability in assessing problems and prescribing solutions should be cultivated, when different perspectives are not reconciled in how Australia acts then the risk of incoherence grows. While slowly improving, personnel in international policy and national security agencies can sometimes lack the “intercultural capability” to understand the priorities, strengths and ways of working of other bureaucratic actors. Too many people from middle to senior management continue to have “single-track” careers, without diverse experience working across the tools of statecraft, especially in terms of experience outside government. Security clearance delays and inflexible working practices further hinder this.

Intelligence and information sharing systems are suboptimal. There is no unified IT system between international policy and national security agencies. Access to intelligence and cables varies enormously between agencies. It is often difficult to identify key working-level contacts between agencies. A common knowledge base and basic network are prerequisites for meaningful and easy collaboration.

The vision in practice

An Australia that uses all the tools of statecraft in a coordinated or integrated way demonstrates strategic coherence:

“Strategic coherence is about ‘getting our act together’, making the most of strengths and reducing weaknesses. It is about different parts of government – and potentially, wider Australian society – utilising their capabilities within an overall game-plan that maximises the chances of success. It necessitates having clear and shared goals and working together to see that they are achieved.”

Through a more coherent, “all tools” approach to its international policy, Australia becomes a more influential regional force capable of protecting and advancing its security and prosperity.

Australia has a deep understanding of how tools of statecraft work in harmony with others, and how these tools have a multiplying effect when deployed in concert. There are refined narratives and strategies for Australia’s international policy and effective implementation of them. Central to this are embedded practices for identifying problems clearly and early, to allow proactive planning that enables Australia to shape its environment. All tools of statecraft – not just the conventional – are valued and understood for their contributions to international policy: education, immigration, media and culture, and the capabilities of state governments, for instance.

This effective international policy is supported by structures and resourcing that enable long-term planning, strategy development and organisation of how the tools of statecraft are deployed. There is an entity with the mandate, capability, mechanisms and cross-departmental reach to coordinate coherent international policy. These structures minimise unproductive tensions within the machinery of international policy, while nurturing the necessary contestability around assumptions, ideas and policy proposals.

More coherent strategies and more effective structures for coordination harness a diverse workforce with a culture of learning. They are also supported by consistent engagement with all relevant stakeholders that contribute to international policy.

The pathways below are presented as discrete, practical options for realising this vision for Australia’s international policy. They are most likely to be successful – and their positive effects multiplied – if implemented in combination. Figure 3 below illustrates how the four pathways – strategy, structure, staff, society – support and are built upon each other.

Pathways

STRATEGY: More coherent strategies and narratives for Australia’s international policy

A coherent strategy and narrative for Australia’s international policy

The government should develop clear, overarching strategic guidance for Australia’s international policy over the next 3-5 years. This guidance should outline Australia’s worldview and global challenges while providing broad guardrails for policy and resourcing by setting out high-level objectives and priorities. This would signal intent to domestic and regional audiences, while having an organising effect on the machinery of international policy. Given that there are several reviews underway for discrete policy areas, overarching strategic guidance can bring greater coherence at this critical juncture.

The Government has options for what this strategic guidance could look like:

- A whole-of-government integrated review or strategy document that comprehensively assesses challenges and provides detailed decision-making and resourcing guidance. The Government would need to consider the scope of this document in terms of whether it focuses on whole-of-government international policy and engagement (more comprehensive than the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper) or a take an approach encompassing both international policy and national security more broadly (for instance, the 2021 UK Integrated Review or the 2022 US National Security Strategy).

- A regular policy statement outlining Australia’s global outlook and security challenges, priorities and resourcing to achieve these objectives, for example annually. This could be a short public document or a major address to parliament by the Prime Minister. Again, the policy scope of this would need to be considered, whether it is tightly focused on international engagement or takes a broader “national security” lens.

- Multiple strategies are developed on discrete themes while retaining coherence around core principles and a centralised resourcing model. Regular speeches by ministers would update how these strategies evolve (the current government’s approach most closely resembles this third option, though it is unclear the extent to which speeches by cabinet ministers reflect a detailed set of strategies internal to government).

The Government should weigh the benefits and downsides of respective options. Before commencing a larger scale process, lessons from previous “integrated review” or “national security strategy” exercises in Australia and similar systems must be considered. Such reviews can carry the risk of becoming so elaborate that they are counterproductive. When done well, however, they can give a bureaucracy the space to generate a narrative and set priorities across government. Research assessing quadrennial reviews and national security strategies in the United States suggests that such processes are more effective at generating organisational change and coordinating the work of agencies than making significant progress on substantive policy.

A more flexible and iterative approach could allow strategic guidance to evolve easily and facilitate more substantive policy development. This would, however, forego the impact of a single core strategy document and will not generate the same integrating effect across government that a large coordination process would, which can be an end in itself.

A high-level political directive about valuing and using Australia’s tools of statecraft

The Prime Minister and senior cabinet ministers should make clear statements about valuing and using all the tools of Australian statecraft, especially what that looks like for key international policy portfolios. This should elaborate on existing statements about an “all tools” approach to statecraft.

The purpose of this is to generate a “whole-of-nation” narrative where all of the Federal Government, state and territory governments, and the community and industry see themselves as influencing and impacted by international policy. A particular emphasis should be placed on the nexus between domestic and international policy.

A greater focus on long-term strategic planning

Broadly, international policy agencies should devote more time and resources to long-term strategic analysis and policy development. In particular, DFAT should boost its foreign policy analytical and long-term planning capability. Structural changes outlined below would support greater long-term planning.

STRUCTURE: Effective structures, coordination mechanisms & resourcing supporting a coherent “all tools” approach to Australian statecraft

A more inclusive and focused approach by Cabinet and ministers across international policy

Embedding a better coordinated approach must start at the top: how ministers make decisions and work together, including through Cabinet and its committees. In particular, the National Security Committee (NSC), the primary decision-making body for international policy and national security, and the Expenditure Review Committee (ERC).

The current Government has included the ministers for climate change and international development in the NSC. This could further expand to include the trade minister. Similarly for the ERC, the Government could consider permanently including the foreign and defence minister on an ex officio basis. While Cabinet committee membership is important, this alone is no guarantee of well-coordinated policy and action (especially given the inevitable political and personality factors involved in any cabinet). The Government should therefore also consider imposing more structure and rigour on Cabinet discussions, including through simulations and scenario planning, as well as contested intelligence assessments and policy proposals. This could start with a review of Cabinet decision making processes at the political level and how bureaucratic structures support this.

Mechanisms for coordinating diplomatic engagement and international development policy between ministers could also be considered to bring greater coherence to how all parts of government contribute to these areas. This could be through a cabinet subcommittee or a more informal process.

A clearly mandated coordinating entity for international policy

Australia needs an organising bureaucratic entity with a clear mandate to coordinate its international policy. Its primary function would be to conduct long-term planning and coordinate how tools of statecraft are used across government to avoid conflicts and generate greater coherence. This means having full visibility over the international policy and engagement of all government agencies. On significant cross-cutting issues demanding fully integrated policy, it could function as a standing body to lead the development and implementation of whole-of-government strategies and narratives without having to set up and resource a special task force.

DFAT would be best positioned to take on this role as an extension of its current functions. This would mean clearly mandating DFAT to lead and coordinate international policy across government, while also providing it the resources to run integrated policy development when needed.

An alternative model would be to boost the central coordination function of PM&C. This would be preferable for a wider remit encompassing both international engagement and national security. A “National Security & International Policy Adviser” with a dedicated staff could play the coordinating function across government and lead on integrated policy when needed. While understanding the important institutional differences between Australia’s cabinet system of government and the United States’ presidential system, lessons could be drawn from the US National Security Council.

A more objective approach to resourcing and using tools of statecraft, while valuing diverse contributions to Australian diplomacy

Tools of statecraft should be used and resourced in manner commensurate to the needs of Australia’s international policy. It is important that the Government interrogates the relative value and importance it attributes to different tools – in particular, that it does not always regard defence and security capabilities as its tools of first resort in most situations.

Specific measures for the Government to consider include:

- Develop decision making frameworks that challenge predetermined mindsets during policy development and budget processes to ensure all relevant tools of statecraft are considered. These could be used in NSC, ERC and SCNS discussions, for instance.

- Tracking expenditure to support Australia’s international policy through an international policy budget statement that summarises and collates all such spending across international and domestic agencies.

More collaborative approaches to coordinated planning, policy and implementation

The government should boost the adoption of more effective means of coordination and collaboration across international policy. Additional training for managers and a “licence to innovate” from agency heads would be essential.

The government should consider various measures, including:

- Encourage and resource more flexible and creative collaboration between agencies at working levels. In particular, ongoing informal collaboration should be prioritised to ensure risks and opportunities are managed proactively.

- Generate permanent structures and dedicated resources to administer whole-of-government futures exercises and simulations (such as red-teaming) with a mandate to stress-test policy. These should be performed at working levels, senior officials level, and in Cabinet.

- Develop whole-of-government implementation frameworks with mechanisms for accountability, resourcing and coordination.

More streamlined systems for intelligence distribution, information sharing and finding key contacts across government

Consideration should be given to developing a modernised, uniform IT system across agencies that engage on international policy and national security issues.

Key features of this system could include:

- Continuing to streamline and expand access to cables, especially for domestic policy agencies.

- Improved systems for distributing intelligence that make access more consistent across government.

- An interagency directory of key working-level contacts across international policy and national security, updated in real-time and with functional descriptions of individual teams. Adoption of a single videoconferencing system between agencies would also make collaboration across government easier.

STAFF: A culture & diverse workforce in government benefiting from structured learning & engagement

Boost the diversity of professional experience

Take a deliberate approach to boosting the diversity of professional experience of people working across international policy. This could include a range of initiatives and targeted incentives, including:

- Consider creating an “international policy graduate program” across government. Graduates would rotate between agencies while developing core international policy and diplomacy skills. This would aim to cultivate diplomacy and international policy capability across government beyond DFAT.

- Enable greater location flexibility for staff across Australian capital cities, especially to attract and retain people from outside government and with diverse experience.

- Expand and embed incentives (and remove disincentives) for staff to move between agencies and outside government through their career.

- Expand the use of secondments between international policy agencies to increase the range of professional expertise working on challenges and broaden the tools of statecraft considered by agencies.

Structured engagement and learning opportunities

Structured engagement and learning opportunities between people at all levels in international policy agencies and experts outside government should be expanded and routinised. In particular, scenario planning, “futures” exercises and simulations that draw in representatives across and from outside government are an effective means of building networks and understanding how an array of tools of statecraft can be brought to bear on complex problems.

A streamlined security clearance system

Consider measures to streamline the Government’s security clearance system to enable a greater circulation of people between agencies and non-government sectors. This could also boost the diversity of public servants working in international policy in terms of their personal background. A formalised process that allows security-cleared external experts to participate more easily in policy planning processes should also be considered.

SOCIETY: Australian Government engaging consistently & broadly at whole-of-nation level

A concerted effort to achieve whole-of-nation buy-in on international policy

Make a long-term, consistent effort at the political and bureaucratic level to build understanding of Australia’s international policy. This will help ensure that all tools of statecraft are properly resourced and respected and that those tools beyond the immediate control of government can be harnessed more effectively.

The Government should consider:

- Developing a strategy for consistently building support across the Federal Parliament, Australian politics and the general public for its international policy.

- Ensuring a cooperative dynamic between ministers and departments in international policy. In particular, minimising competition for influence and resources.

- Encouraging state and territory governments at the political level to regard themselves as actors in international policy while operating within broad guidelines set by the Federal Government.

Develop greater capability to engage external expertise, domestic policy agencies and other actors

While the Federal Government already has significant business engagement capability, an enhanced “all tools” approach requires greater capacity to coordinate entities that hold tools of statecraft beyond government control:

- Develop programs and mechanisms to bring external expertise into government policy development more easily and flexibly – in particular, scientific and technological expertise.

- Develop a dedicated domestic policy engagement capability that connects international policy agencies with other federal, state and territory agencies. In particular, this capability should focus on how international policy can harness Australian expertise and assets to deliver public goods (e.g., public health and vaccine delivery; infrastructure) and influence international standards.

- Develop routinised approaches (especially in DFAT) to consistently engage non-government actors such as the tertiary sector, NGOs, community and diaspora groups, media, and sports and cultural organisations.

Contributors

Thank you to those who have contributed their thoughts during the development of this paper. Views expressed cannot be attributed to any individuals or organisations involved in the process.

Alicia Mollaun

Equity Economics and Development Partners

Benjamin Day

ANU College of Asia & the Pacific

Bridi Rice

Development Intelligence Lab

Caitlin McCaffrie

Centre for Policy Development

David Andrews

ANU National Security College

Fiona Tarpey

Australian Red Cross

Richard Moore

International Development Contractors Community

Susannah Patton

Lowy Institute

William Leben

ANU National Security College

William Stoltz

ANU National Security College

Three further contributors with expertise in international engagement, trade and governance who preferred not to be named.

Consultations were also held with 20 current and former officials with expertise and experience working across Australian foreign, trade, development, intelligence and defence policy.

Editors

Melissa Conley Tyler

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons license. You can reprint or republish with attribution.

You can cite this paper as: Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue, What does it look like for Australia to use all tools of statecraft in practice. (Canberra 2023): www.asiapacific4d.com

Photo on this page: TStudio, ‘Sound Operator Console’, used under Creative Commons

This paper is the product of Stage II of ‘Shaping a shared future — deepening Australia’s influence in Southeast Asia and the Pacific’, a program funded by the Australian Civil-Military Centre.

Supported by: