What does it look like for Australia and Southeast Asia to...

Develop a Joint Agenda for Maritime Security

Published: May 2023

Executive Summary

Maritime security is vital for Australia and Southeast Asia, making it a shared priority issue for the region. With Australia’s future economic and energy security linked to the Southeast Asian region, maritime trade activities remain integral to prosperity, and open sea lines of communication are vital. Supporting maritime security directly contributes to Australia’s national security interests.

Australia must have a coherent and coordinated response to emerging maritime security challenges. Climate change is a priority issue for all nations, and aligns maritime security and safety with the environment, sustainable development and Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HADR). Food security is an emerging challenge, with maritime boundary disputes, over-exploitation of fishing stocks and grey-zone activities a growing issue of concern. Resource exploration is increasing, linking energy and maritime security for countries in the region and becoming a potential source of conflict, making the capability to survey and enforce environmental protections critical.

Meeting these challenges will require Australia to become a trusted maritime security partner, with maritime cooperation serving as a key pillar of engagement with the region. While this report uses the term ‘Southeast Asia’, it is a complex region consisting of eleven diverse states, each with their own set of maritime security interests. There cannot be a ‘one size fits all’ approach to Australia’s partnership with Southeast Asian countries. Australia’s most effective interventions will stem from its experience, best practice and lessons learnt in managing its own marine environment, and knowledge gained from in-depth engagement in Pacific maritime security, in order to build Southeast Asian maritime capacity.

Australia must integrate defence, diplomacy and development to become a reliable and capable partner. Diplomatic efforts will be required to advocate for international law while responding to complex and sensitive border disputes, which have created challenges and affected cooperation. There is scope for greater expansion of Australia’s development cooperation program to address challenges in coastal communities, where a lack of education and economic opportunities contribute to high seas security issues. While the breadth of issues encompassed by maritime security can seem overwhelming, the breadth of agenda also provides opportunities for a comprehensive and integrated approach.

PATHWAYS FOR AUSTRALIA AND SOUTHEAST ASIA TO DEVELOP A JOINT AGENDA FOR MARITIME SECURITY

Enhancing Existing Partnerships

- Support implementation of the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific

- Boost the provision of maritime capacity-building programs, extending training to both civilian and government officials

- Aim to become the go-to provider for training on legal frameworks governing maritime security, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

- Increase human resource development through expansion of the Australia Awards and other programs

Research and Coordination

- Undertake research on lessons learned from current capacity-building

activities in the tri-border area between the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia - Prioritise funding for environmental activities and cooperation, such as

implementation of the ASEAN Regional Action Plan for Combating Marine Debris

Strengthened Maritime Cooperation

- Build on existing agreements to increase information-sharing and joint analysis to improve maritime domain awareness

- Support the development of national and regional maritime security strategies

- Transfer lessons from maritime activities in the Pacific to projects in Southeast Asia

Single Point of Contact System

- Establish an agreed Single Point of Contact (SPOC) for maritime security in each country

- Encourage regular dialogues between SPOCs and other maritime actors

Strengthened Diplomatic Engagement

- Strengthen Australia’s diplomatic presence in the region

- Include maritime security in the development of Australia’s trade and economic strategy for Southeast Asia

An Australian Maritime Security Strategy

- Communicate Australia’s priorities through a clearly articulated national maritime security strategy for engagement in the Indo-Pacific

Supporting Emerging Australian and ASEAN Maritime Security Leaders

- Connect ASEAN and Australian youth, for example through development of a joint Youth National Security Strategy and an expanded ASEAN-Australian emerging leaders program (A2ELP)

Why it Matters

The Australian Government has signalled that it is looking for new initiatives, ideas and ways of engaging more deeply with Southeast Asia. Australia and Southeast Asian countries rely on maritime security, making it a shared priority issue. Now is the ideal time to develop a joint agenda for how Australian can work with Southeast Asia in the maritime domain.

Southeast Asia is one of the busiest maritime areas in the world. Maritime security is vital to the region, requiring coordination of all the elements of Australia’s statecraft – including defence, development and diplomatic engagement – to meet the challenge.

From a defence perspective, maritime security matters because of the risk of conflict and grey-zone activities in the maritime spaces of Southeast Asia. The rules-based international order in the maritime domain is vital to Australia’s and Southeast Asian nations’ national interests and is under pressure throughout the Southeast Asian region. Infringement of territorial waters is just one of the problems in international order.

Working to support Southeast Asian nations to strengthen maritime security will directly contribute to Australia’s national security interests. Australia’s domestic civil maritime security strategy explicitly states that a stable global maritime environment underpins a secure domestic maritime domain.

Nontraditional maritime security threats include irregular migration, environmental issues such as the illegal exploitation of natural resources, marine pollution, lost or discarded fishing gear which contributes to marine plastic pollution, illicit trafficking, piracy and terrorism. Political stability and freedom of movement are integral to regional peace and security; both are enhanced by maritime security.

Australia’s future economic security is linked to prosperity in the region, with maritime trade activities integral to Australian and Southeast Asian economic growth. 99 per cent of Australia’s imports and exports by volume rely on international shipping. The Strait of Malacca, bordering Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, is one of the world’s most important trading routes; it is the fastest route connecting the Indian and Pacific Ocean, through which a quarter of the world’s trade passes.

Australia is an island nation with one of the longest coastlines and largest Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) in the world. Australia’s strategic calculus is therefore shaped by its view as an island reliant on trade and shipping. It is critical for the sea lines of communication that pass through Southeast Asia to remain open to enable supplies to reach the Australian continent. Maritime security is directly linked to energy security and Australia’s ability to import fuel, with 90 per cent of total transport fuels imported by sea, leaving Australia in a critical situation if the sea lines of communication came under threat.

Resource exploration is an emerging area that will require engagement of all three pillars of defence, diplomacy and development. The capability to survey and enforce environmental protections will be critical. For countries in the region, energy and maritime security are increasingly linked and are a potential source of conflict. This was demonstrated in a 2014 confrontation between Chinese and Vietnamese navies and coastguards over the deployment of a Chinese oil rig and resource exploration ships in Vietnamese-claimed territorial waters. More recently, vessels and aircraft from several agencies in China have consistently harassed Malaysian hydrocarbon exploration operations, adding a potential complication to the latter’s dependence on oil and gas revenue from the South China Sea.

The region’s vulnerability to climate change and extreme weather events aligns maritime security and safety with the environment, sustainable development and Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HADR). For countries like Vietnam, a one metre rise in sea level could affect 11 per cent of the population and 7 per cent of its agricultural land. Responding to climate change in the maritime space will require a region-wide and whole-of-government response, including the integration and application of new technologies into the maritime security domain.

Food security is an emerging challenge, impacted by issues such as Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (IUU) and maritime boundary disputes. It is an area where Southeast Asia countries regularly seek external assistance. Both traditional and nontraditional aspects of maritime security present regional challenges that are difficult for countries to respond to individually.

Perspectives

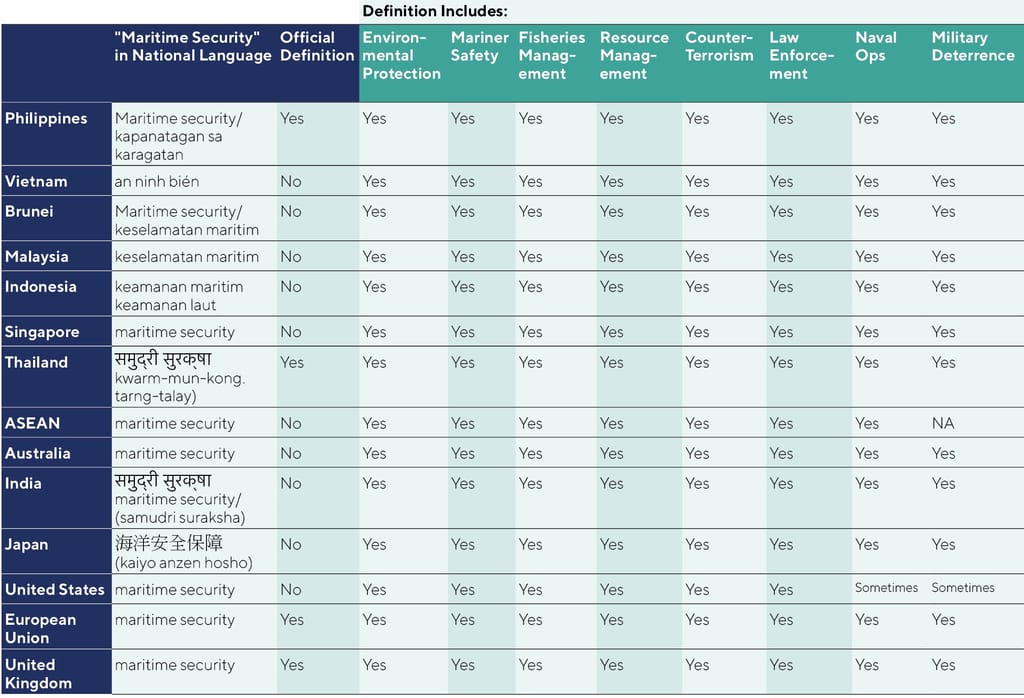

AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVES

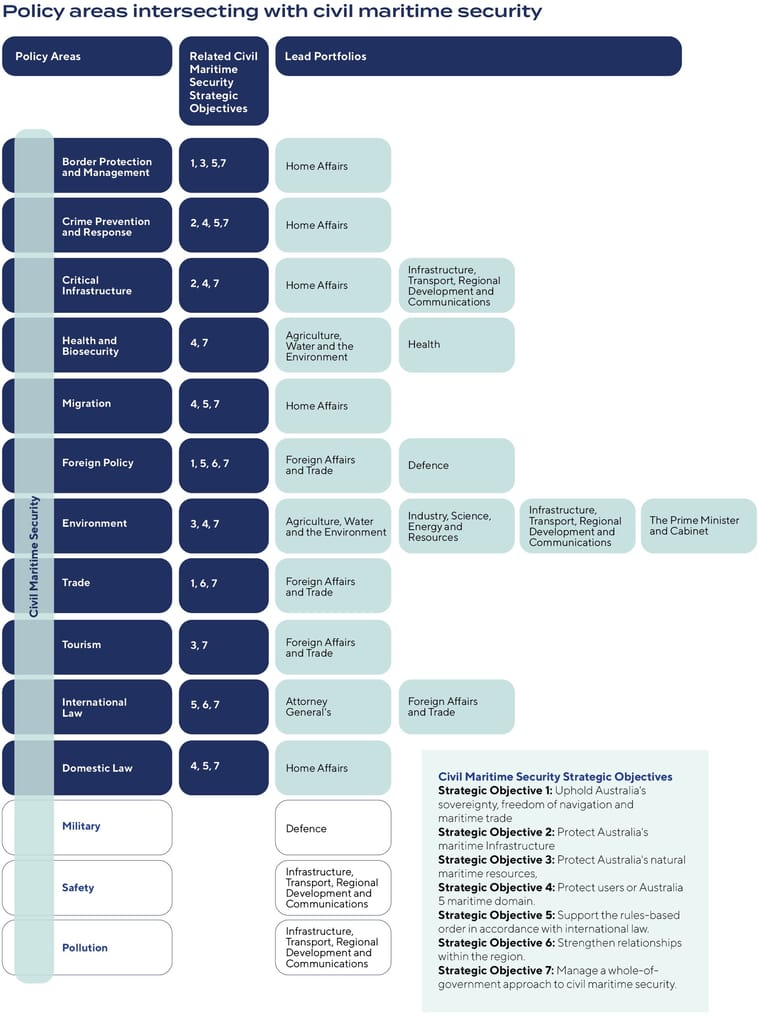

Australia does not have a formal definition of maritime security, making it a broad and ambiguous concept subject to the interpretation of departments and government actors based on their responsibilities and objectives. Many different policy areas across government have a maritime dimension, making Australian maritime security a whole-of-government effort that relies on more than 20 federal government departments and agencies.

Some Australian maritime security objectives are outlined in the Australian Government Civil Maritime Security Strategy, released in 2022. The strategy includes upholding Australia’s sovereignty and freedom of navigation, protecting Australian maritime infrastructure and natural maritime resources, protecting users of Australia’s maritime domain, supporting the rules-based order in accordance with international law, and strengthening relationships within the region.

DEFENCE PERSPECTIVES

From a Defence perspective, Australia’s long-term maritime objective is the deterrence of hostile surface fleets, aircraft and submarines while maintaining the Australian Defence Force’s ability to deploy to the region and protect Australian ports from sea mines, and support civil law enforcement and coastal-surveillance operations. The 2020 Defence Strategic Update identifies grey-zone activities as a growing issue of concern to Australia’s maritime security.

The Australian Defence Force will increasingly be required to respond to areas outside of its traditional deterrence function. The recently signed Indo-Pacific Partnership for Marine Domain Awareness (IPMDA) between the members of the Quad (Australia, India, Japan and the United States) is an example of the increasing focus on combating non-traditional maritime security issues. The agreement aims to provide information to South Pacific, Indian Ocean and Southeast Asian nations to monitor dark shipping, improve data on climate and humanitarian events, and protect their fisheries.

DIPLOMATIC PERSPECTIVES

Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) pursues diplomacy to uphold security and maritime cooperation through partnerships at the bilateral, regional and multilateral levels. DFAT, together with Defence, is one of the first points of contact for regional maritime cooperation. The 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper pinpoints “safeguarding maritime security” as core business to maintaining a secure and stable Indo-Pacific.

The Australian Civil Maritime Security Strategy aims to support the rules-based order in accordance with international law, which requires DFAT to engage on Australian treaty obligations, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), boundaries delimitations, and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). DFAT is the lead government agency on initiatives including The Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime, and resource exploration and revenue sharing negotiations between Timor-Leste and Australia in the Great Sunrise Field.

The Australian Government has committed to an Indigenous diplomacy agenda and gender equality. These are both areas that Australia is currently focusing on, and has made an announcement on adopting a First Nations foreign policy and promoting greater gender equality through its development program.

DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVES

Coastal communities experiencing poverty are a significant contributing factor to high seas security issues, including piracy, terrorism, radicalisation, movement of contraband and human trafficking. The impact of poverty on maritime security issues is highlighted in the tri-border area between Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. Australia seeks to address these issues through its development cooperation assistance to the region. For example, Australia’s development partnership with the Philippines has a substantial focus on the island of Mindanao, home to some of the region’s poorest and most vulnerable communities. Australia’s development agenda in the region promotes stability through investment in education to increase access and reduce school dropout rates, which have long-term economic and social implications.

“I think from an Australian defence policy perspective, in many ways we agree… that not all the security challenges in the region should be seen through the lens of great power competition. A lot of what the Australian Defence Department and the ADF has been doing with our regional partnership has been on the broader range of security agenda.”

- Secretary of the Department of Defence Greg Moriarty

SOUTHEAST ASIAN PERSPECTIVES

Territorial disputes in the South China Sea continue to be a primary area of concern for many Southeast Asian nations. Grey-zone activities, including the presence of foreign maritime militia, are increasing as the economic benefits of accessing fishing grounds and maritime resources become paramount. As a result, many Southeast Asian nations have expressed a desire for training on international governance and regulation surrounding maritime security and territorial claims, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Budget limitations impede regional navies’ ability to defend the coastline, to combat armed robbery and terrorism, and to protect oil exploration and sea transportation. Unlocking countries’ economic potential will require a range of measures including boosting maritime connectivity, mitigating mismanagement, lowering logistic costs, curbing commodity prices and inflation, and growth in underdeveloped areas. Investments by countries such as Japan and China for maritime infrastructure projects have bolstered the position of nations such as Indonesia as a global maritime hub.

The blue economy concept, the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth and the management of rich maritime resources, is of emerging priority for Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries. Food security challenges, exacerbated by increasing Illegal Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing, have focused nations’ attention on securing resources in the maritime domain.

- Shared Awareness and Exchange of Information and Best Practices;

- Confidence Building Measures based on International and Regional Legal Frameworks, Arrangements and Cooperation including the 1982 UNCLOS, and

- Capacity Building and Enhancing Cooperation of Maritime Law Enforcement Agencies in the Region.

(Source: ASEAN Secretariat)

- 1997 Declaration Transnational Crime

- 1998 Manila Declaration on the Prevention and Control of Transnational Crime

- 1999 Plan of Action to Combat Transnational Crime

- 2002 AMMTC Work Programme to Implement the 1999 Plan of Action

- 2003 ASEAN Concord Il

- 2004 Vientiane Action Programme

- 2009 ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint

- 2015 Kuala Lumpur Declaration in Combating Transnational Crime

- 2015 ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint 2025

(Source: Zhen Sun, NUS Centre for International Law)

Areas of maritime cooperation, in accordance with the principles of international law including the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea:

- cooperation for peaceful settlement of disputes; promoting maritime safety and security, and freedom of navigation and overflight; addressing transnational crimes, including trafficking in persons or of illicit drugs, sea piracy, robbery and armed robbery against ships at sea.

- cooperation for sustainable management of marine resources; to promote maritime connectivity; to protect livelihood of coastal communities and to support small-scale fishing communities; to develop blue economy and to promote maritime commerce.

- cooperation to address marine pollution, sea level rise, marine debris, preservation and protection of the marine environment and biodiversity; promoting green shipping.

- technical cooperation in marine science collaboration; research and development; sharing of experience and best practices, capacity-building, managing marine hazards, marine debris, raising awareness on marine and ocean-related issues.

(Source: ASEAN Secretariat)

ASEAN Sectoral Bodies

Transnational Crime

Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime

Law

Law Ministers' Meeting

Defence

Defence Ministers' Meeting

Transport

Transport Ministers' Meeting

Key Regional Forums For Maritime Security Cooperation

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

- ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting (ADMM)

- ADMM plus Dialogue Partners (ADMM-Plus)

- ADMM Expert Working Group on Maritime Security (ADMM-EWG-MS)

- ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime (AMMTC)

- ASEAN Naval Chiefs Meeting (ANCM)

- ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF)

- ASEAN Maritime Forum (AMF)

- Expanded ASEAN Maritime Forum (EAMF)

OPPORTUNITIES FOR ALIGNMENT

There is no single Southeast Asian view on maritime security, meaning there cannot be a ‘one size fits all’ approach to Australia’s partnership. Individually, countries may not know what they want or need and prefer Australia to be confident in what it can offer the region. Australia must at the same time ensure it works collaboratively and empowers local partners in order not to be perceived as simply telling the region what to do.

Maritime cooperation serves as a key pillar of Australia’s engagement with the region. Australia can play a role in supporting national capacity to patrol and defend territorial waters through providing technical and English language training and encouraging people-to-people linkages. English language capability, supporting the communication and coordination between partners, will become increasingly important in response to emerging maritime security issues including peacekeeping and Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HADR) operations. Australia can share its knowledge and experience in managing the marine environment with Southeast Asian partners.

Climate change is a priority concern for Australia and Southeast Asian nations, with Southeast Asian countries expected to be among the world’s worst affected by climate change. There is potential for cooperation to support economies to transition towards a green economy with renewable energy projects such as offshore windmills, and widening the use of green technology and low emission fuels, including clean hydrogen, to reduce emissions in maritime and port operations. The recent landmark Australia and Singapore Green Economy Agreement is an example of what can be achieved, with the potential for cooperation to be extended out to other countries in the region.

“ASEAN recognises the multi-faceted nature of maritime issues and therefore commits to a holistic, integrated and comprehensive approach to address them.”

Case Study: KA22 Exercise Kakadu

Exercise Kakadu is the Royal Australian Navy’s (RAN) flagship biennial regional international engagement activity. In 2022, Exercise Kakadu concluded a two-week long multinational maritime exercise in northern Australia involving 15 vessels, 30 aircraft and around 3,000 personnel from more than 20 countries. It was the 15th biennial exercise and had the theme of ‘Partnership, leadership and friendship’.

During the exercise, multinational forces carried out drills to allow participating nations’ forces to enhance their capabilities in seamanship, humanitarian and disaster relief, maritime law enforcement operations, maritime warfighting, and anti-air warfare combined scenarios.

Exercise Kakadu remains a vital tool for building relationships between participating countries through providing opportunities for defence personnel to immerse themselves in the way partner navies do business, creating enriching learning and development opportunities.

Barriers and Challenges

Border disputes between neighbouring countries can create challenges and impact cooperation if they are not dealt with diplomatically. In 2021 the Indonesian Government suspended a joint maritime patrol with the Australian Border Force in response to the Australian Government burning three Indonesian fishing vessels caught illegally fishing in Australian waters. Despite Indonesia supporting similar IUU measures in its own waters, the response highlights the sensitivity in dealing with maritime cooperation as marine environmental protection becomes a priority for nations, requiring open communication between countries.

Despite long-standing bilateral defence ties within the region, some countries, including Indonesia and Malaysia, have raised concerns that Australia’s decision to acquire nuclear-propelled submarines through the AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom, United States) agreement could threaten regional peace and prosperity by undermining nuclear nonproliferation or triggering a regional arms race.

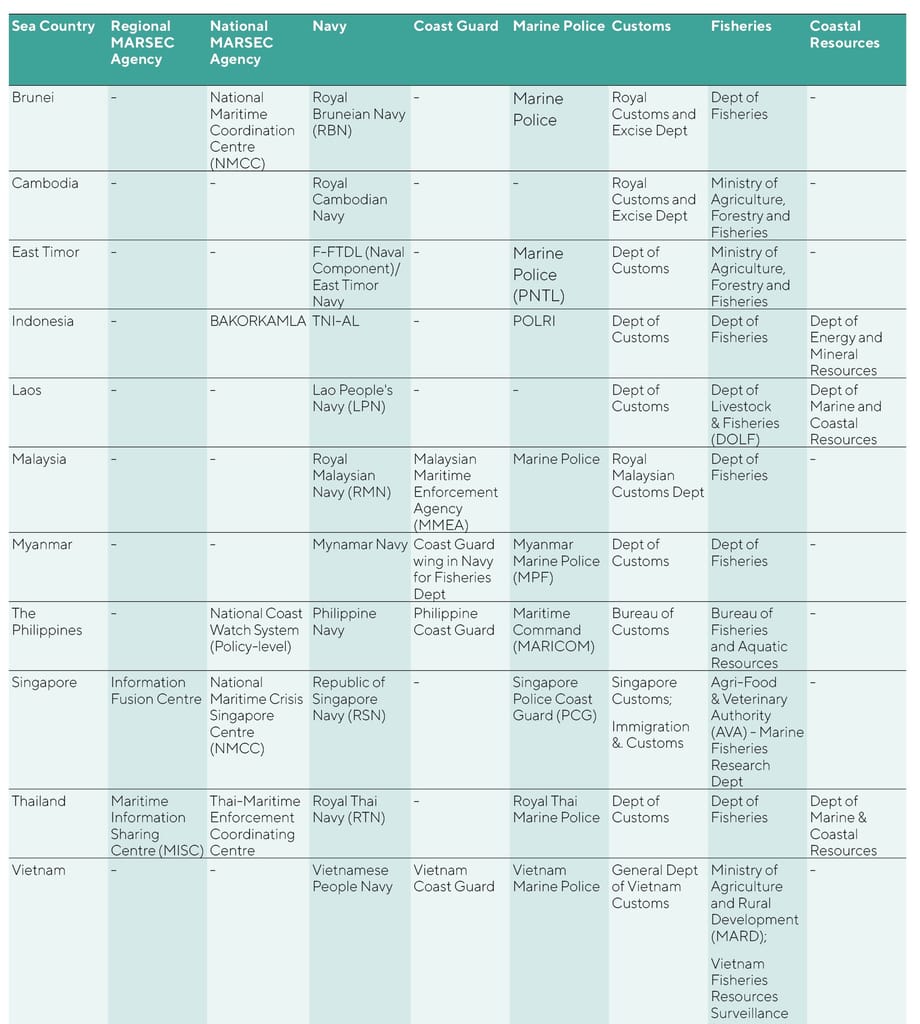

There is a lack of coordination across government agencies on maritime security, and a lack of clarity around the maritime first point of contact, or Single Point of Contact. This is an issue across the region and in Australia, with each country having their own unique and at times ad hoc set-up, making coordination and communication challenging.

A lack of human development in some coastal areas (for example the tri-border area between the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia, which includes the Sulu-Celebes Sea region) enables transnational crime to exploit the opportunities afforded by porous borders, creating potential risks for Australia and ASEAN states. Maritime security must therefore also be addressed on land.

Australia’s unique geography and history complicates its engagement with the region. As a Western nation, Australia has to overcome the challenges of cultural differences in Southeast Asia, whereby Australia is not seen as belonging to Asia. This can lead to cultural differences in negotiations and engaging with ASEAN states. Australia must ensure engagement comes from a place of equality and respect, acknowledging where its strengths are and lessons that can be shared, and avoid a top-down approach.

Political uncertainty and wavering political will in Australia’s engagement with the region on the important issue of maritime security has impacted progress. Australia is sometimes suspected of taking its cue from key allies such as the United States, leading to perceptions that Australia is constrained by alliance relationships, and a follower not a leader. Australia must commit long-term to developing solutions with a region that is geographically, socially and economically significant.

The breadth of issues maritime security encompasses means that it can be difficult to define. While there is a risk that a joint agenda becomes too overwhelming, making it difficult to adopt an integrated approach, there is simultaneously an opportunity for a comprehensive approach to illuminate a way forward.

Southeast Asian Maritime Security (MARSEC) Agencies

Australian Agencies with Maritime Responsibilities

The Vision in Practice

What does it look like for Australia and Southeast Asia to develop a joint agenda for maritime security?

The Australian Government will bring all the elements of statecraft together to meet the maritime security challenges facing Southeast Asia.

The Australian Government is a capable and reliable partner in the region on maritime security issues, confident in its approach in what it has to offer to Southeast Asian nations. Australia’s engagement is genuinely and deeply consultative. Australia’s assistance empowers local populations, acknowledging where there are shared problems and common challenges, and pooling knowledge to assist both Australia and the region.

As a trusted maritime security partner in the region, acting with shared interest for a shared future, Australia is seen as engaging with the region on its own behalf, representing its own interests as a true partner with the region.

Australia is a leader in maritime domain awareness (MDA), ensuring an integrated defence, diplomacy and development approach to strengthen MDA across the region. Key to addressing maritime security challenges regionally and nationally is strengthening the national ability to understand what is happening at sea that could impact safety, security, economy or environment. In developing an MDA architecture, Australia and the region take an incremental approach that pursues realistic goals and ensures ownership and sustainability. MDA architecture focuses not only on threats or crime, but ensures measures that benefit the larger blue economy and regional ocean governance.

The Australian Government will work to improve regional maritime domain awareness systems through better information sharing, supporting the development of a Single Point of Contact system in partner countries, and joint analysis to allow them to react faster to incidents and set regional priorities. These activities will require increased coordination between defence and non-defence agencies in order to share data in non-traditional ways.

Australia continues to be an advocate for international law, being a respected voice on international platforms in support of a fair and open region.

Australia will share its knowledge and experience with Southeast Asian partners by compiling and communicating best practice. Australia has extensive experience in fisheries management, including dispute resolution with neighbouring countries and expertise in managing the marine environment. Australia also has deep expertise in mineral resource exploration and extraction. Australia’s own experience in developing processes to bring together defence, diplomacy and development to discuss issues on maritime security is shared to assist partner governments in effectively addressing similar issues.

The Australian Government builds on its strong record of providing capacity-building programs, expanding the scope and scale of its development cooperation program by aligning with like-minded development partners. Australia explores opportunities to coordinate with development partners such as the Quad and multilateral development banks, ensuring a cooperative development agenda for the region.

Australia strongly collaborates and cooperates with Southeast Asian nations on research and development in key areas of marine scientific research. Australia strengthens mentoring partnerships with higher education and research institutions across the region.

Australia’s development assistance addresses coastal development issues, with a coordinated approach across defence, diplomacy and development addressing human development issues and their impact on maritime security.

Through its newly-adopted First Nations Foreign Policy, Australia pursues opportunities for First Nations communities’ leadership within national maritime security discourse, decisions and outcomes based on values of reciprocity, understanding, respect and inclusion. Australia’s First Nations foreign policy approach centres on the values, voices and practices of First Nations people and culture enhancing Australia’s engagement in the region.

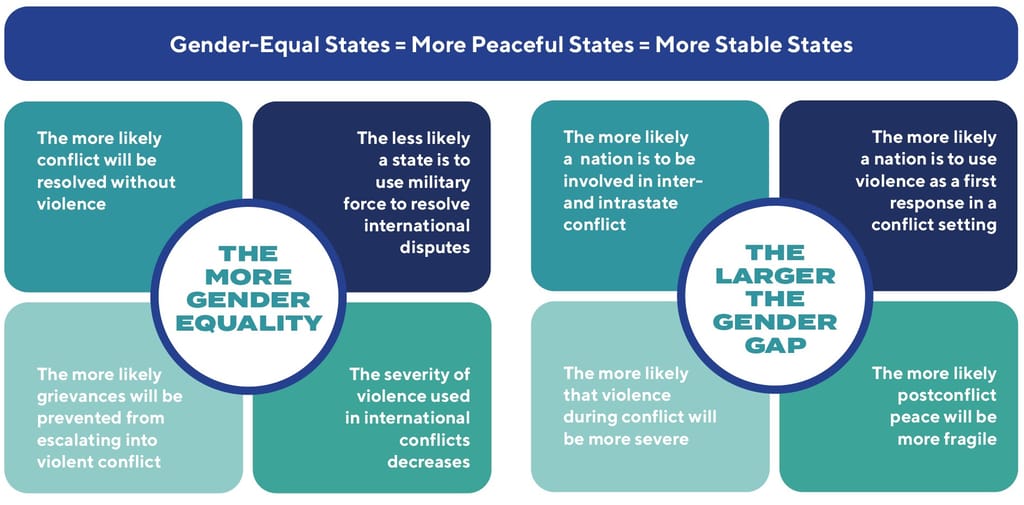

Australia is recognised as a global leader on gender equality and ensures that this is embedded across its maritime security policy. Australia leads by example in promoting gender equality in the region in line with the strong evidence from research on women, peace, and security that women’s empowerment and gender equality are associated with a country’s security and stability. Australia works to implement its own National Action Plan on Women Peace and Security 2021-2031 across different government agencies.

The Role of Gender Equality in State Stability

Pathways

To achieve this vision, the following pathways were identified.

Enhancing Existing Partnerships

There is an opportunity for Australia to further collaborate with Southeast Asian nations to support the implementation of ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. If approached properly, Australia’s support for the strategy would be welcomed by the region, ensuring engagement is based on mutual benefit and is seen as valuable in itself and not through the lens of geostrategic competition.

Australia can build on its experience and reputation as a provider of military maritime capacity-building programs, extending training to both civilian and government officials. Australian defence cooperation activities should continue to incorporate, and expand where possible, English training programs as a pathway to overcome barriers and pave the way for deeper collaboration between defence agencies. Australia’s provision of new technology and technical assistance can also be used as a pathway for greater defence cooperation. Australia can provide support in the form of in-country training in the use of open-source intelligence (OSINT) and unclassified surveillance platforms that exist in the commercial sector (such as satellites).

Australia can be the go-to provider for training on legal frameworks governing maritime security, including the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea. The Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS), supported by the Royal Australian Navy, is already offering a wide range of capacity-building in law of the sea, ocean policy and maritime security.

Human resource development will be a key intervention to build maritime security capacity. The Australia Awards program is a mechanism already in place that can be utilised not just for technical training, but to develop strategic thinking. The scholarships and short courses offered are welcomed by the region and are in high demand. A ‘Women in Leadership in the Security Sector Short Term Award’, currently offered to Indonesian government agencies including Foreign Affairs, Marine Affairs and Fisheries, shares lessons and best practice between Australia and Indonesia. This could be extended out to the region.

Australia could also expand the ASEAN-Australia Defence Postgraduate Scholarship Program (AADPSP), an innovative strategic studies program for defence officials from Southeast Asia and Australia, and the Australian Command and Staff Course (ASCS) at Weston Creek, Canberra. For many ASEAN member states, the ASCS enables the transfer of strategic and operational knowledge, including the maritime domain, which are lacking within their defence establishments. Both the ASCS and AADPSP are also means for ASEAN military officials to build relationships with Australian counterparts.

Case Study: Australian Defence Cooperation Program in Cambodia

Australia’s Defence Cooperation Program to Cambodia focuses on capacity-building in key areas including education and training, maritime security, and organisational reform to support the professionalisation of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces.

To develop English language capacity within the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, Australia supports attendance of Royal Cambodian Armed Force personnel at the College of Social Sciences and Languages at the Cambodian National Defence University and the Defence International Training Centre in Melbourne, Victoria.

To build professional capacity in the Cambodian Armed Forces, the Australian Defence Cooperation Scholarship Program provides scholarships for personnel to attend Australian universities to obtain a Graduate Diploma or Masters Degree in English teaching, Counterterrorism, Maritime Security, human resource management, financial management, logistic management, and strategic thinking.

Case Study: Australia Philippines Defence Cooperation Joint Australian Training Team – Philippines

The Australian Defence Force Joint Australian Training Team – Philippines program provides training and education opportunities for personnel from the Armed Forces of the Philippines, Philippines Coast Guard and Department of National Defence.

Training is provided through Mobile Training Teams (MTT), which visit the Philippines to conduct training activities to strengthen interoperability between the two countries. The MTT provide training in fields such as command and operations law, maritime strategic studies, defence intelligence research and analysis, and aviation safety.

The flexible approach of the MTT has meant training can be organised quickly to satisfy newly identified training requirements.

Case Study: Australia Vietnam Defence Cooperation Program: English Language Training

The Australia Vietnam Defence Cooperation Program sponsors the biannual Military Regional English Language Schools Conference. Co-hosted by the Vietnamese People’s Army and the Australian Defence Force, the conference aims to enhance the partnership between regional Defence language schools and consists of presentations, workshops and discussions on developing and improving military English language training.

Australia is one the largest providers of training for the Vietnamese People’s Army, with an alumni cohort comprising more than 1000 officers. Every year, more than a hundred Vietnamese Army personnel train in both countries, studying, exchanging experiences and building relationships to strengthen cooperation across the region.

Case Study: Australia Thailand Defence Cooperation Scholarship Program

Under Australia’s Defence Cooperation Scholarship Program to Thailand, scholarships are provided to Royal Thai Armed Forces for postgraduate study at Australian universities in a wide variety of fields, including International Relations, Maritime Policy and Information Technology. The scholarship program also includes 300 hours of English language training to enable candidates to meet the English language requirements of Australian universities.

The Australian Defence Force also sponsors joint military training and education courses in Australia. Training courses vary in length from one or two days to 12-months, and cover specialist and general training provided by the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Navy, Australian Army, and Royal Australian Air Force. Places are offered to Royal Thai Armed Forces members and government civilians.

Research and Coordination

Australia can contribute to a joint development agenda in the tri-border area between the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia through research and development. The region’s porous borders present significant challenges, from kidnapping and human trafficking to the movement of illicit substances and contraband, but also provide an opportunity where increased cooperation can make a significant difference. A development agenda should aim to lift the human development index in the region over the long term, through a combination of upskilling, promotion of trade and investment, and the creation of job opportunities in the region. Australia can undertake a case study of current capacity-building activities in the region to garner lessons learned and determine what needs to be done differently to be more effective in hardening borders and addressing key development challenges.

Australia should be a strong partner on international environmental cooperation through prioritising funding for environmental activities. In addition to marine scientific research, Australia can further cooperate on environmental issues through supporting the ASEAN Regional Action Plan for Combating Marine Debris in the ASEAN member states.

Case Study: Australia National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS)

ANCORS is a multidisciplinary university-based centre delivering specialised research, advisory services, education and training in ocean law and policy, maritime security, and marine resources management. ANCORS builds the legal capacity of country across the region through offering short courses in a range of areas including fisheries management, international fish trade, international fisheries law, law of the sea, maritime regulation and enforcement.

In 2021 ANCORS, in conjunction with the Expanded ASEAN Maritime Forum and the Centre for International Law, implemented an e-Training Course on Alternative Resolutions to Maritime Boundary Disputes. The course provided training to government officials responsible for negotiating maritime boundary issues with their neighbours.

This is an example of a program that could be continued to further training for relevant government officials in the region.

Case Study: Australia ASEAN and Mekong Program

The ASEAN – Australia Counter Trafficking is a 10-year partnership funded by the Australian Government to support ASEAN member states in implementing and reporting on their obligations under the ASEAN Convention against Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children. The partnership also supports mutual learning and best practice on the use of technology to combat human trafficking, with ASEAN member states engaging in a series of workshops on collecting and using digital evidence to combat new forms of trafficking and reduce the reliance on testimonies.

In partnership with the International Labour Organization, Australia also supports the TRIANGLE in ASEAN program to promote safe and fair migration within the ASEAN region and ensure that the benefits of labour migration are equally enjoyed by men and women. The program is working to deliver technical assistance to support the contribution of labour migration to equitable, inclusive and stable growth in the ASEAN region. Target beneficiaries include migrant and potential migrant workers and their communities from and within the Greater Mekong Subregion and Malaysia, tripartite constituents, recruitment agencies, civil society, and the private sector.

These programs demonstrate Australia’s strengths in delivering technical assistance to the region.

Strengthened Maritime Cooperation

Australia can strengthen regional maritime domain awareness through increased information sharing and joint analysis to allow countries to react faster to incidents and set regional priorities. This can be achieved through building on existing agreements and arrangements, including with the regional Information Fusion Centre in Singapore.

The Australian Government can actively support the inclusion of MDA activities into broader bilateral and multilateral maritime security frameworks through supporting national and regional maritime security strategies. Australia can support partners that are developing their own vision and priorities, and, where requested, can offer to work with other nations to support their planning processes. The recently released 2022 Cambodian Defence White Paper, developed in partnership with the Australian Department of Defence, was part of a program that supported a range of areas in maritime security, strengthening cooperation between the two countries while working on areas of mutual benefit. This example of Australian assistance could be offered to other Southeast Asian countries where the initiative would be welcomed.

Australia should use knowledge and experience gained from maritime activities in the Pacific to inform its engagement in Southeast Asia. Australia’s experience supporting maritime domain awareness (MDA), maritime security and infrastructure development across the Pacific has demonstrated strengths and weaknesses and provided valuable lessons. Lessons from the Pacific Maritime Security Program (PMPS) can be used to inform projects around MDA capabilities across the Southeast Asian region.

Case Study: Singapore Information Fusion Centre (IFC)

Established in 2009, the Information Fusion Centre (IFC) is a regional Maritime Security centre situated at the Changi Command and Control Centre and hosted by the Republic of Singapore Navy. The Australian Royal Navy deploys a liaison officer to Singapore to support the work of the Centre.

The IFC facilitates information sharing and collaboration between partners to enhance maritime security. The IFC has been at the forefront of providing information to regional and international navies, coast guards and other maritime agencies to deal with the full range of maritime security threats and incidents. This includes piracy, sea robbery, maritime terrorism, contraband smuggling, illegal fishing and irregular human migration.

This is a successful example of the region working together to strengthen maritime domain awareness.

Case Study: Partnership between Australia and the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agencies (FFA)

The Partnership between Australia and the FFA is a good example of a successful program that could be replicated to enhance maritime security in Southeast Asia.

Pacific fisheries are vital to the region’s food security, long-term economic growth and way of life. Through its partnership with the FFA, Australia works closely with the region to strengthen fisheries management, development and security cooperation, ensuring members maximise the long-term social and economic benefits from the sustainable use of the region’s shared offshore fishery resources.

One of the highest priorities of the Australia-FFA partnership is to ensure the security of the Pacific region through combating illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, a key regional and global threat to the development of a sustainable ocean economy.

Single Point of Contact System for Maritime Security

The Australian Government can work with Southeast Asian partners to establish an agreed Single Point of Contact (SPOC), or lead agency, for maritime security in each country that is able to transmit information at the national level. SPOCs can be a cost-effective solution to disseminate and share information, discuss challenges and develop proposals, and can be implemented with few administrative, legal or diplomatic hurdles. For example, choosing principal civil maritime agencies such as the Indonesian Maritime Security Agency (Badan Keamanan Laut Republik Indonesia) and the Australian Maritime Border Command, would be a simple step with a significant impact. Australia can also support formal agreements, or Memoranda of Understanding, to clarify expectations and provide basic operating procedures. This requires interagency support.

Australia should encourage regular dialogues of SPOCs and other maritime actors on maritime domain awareness to assist in developing a shared understanding of priorities across the region. Singapore’s Information Fusion Centre (IFC) regularly holds Shared Awareness Meetings (SAM) where navies, coast guards, other maritime agencies and members of the shipping community discuss maritime security issues and challenges. Such dialogues facilitate operational cooperation, build trust and relationships as well as provide transparency to planned activities.

“Investing in our Indo-Pacific regional partnerships remains essential. Australia’s focus must be to deepen its engagement and collaboration with partners across Southeast Asia.”

Strengthened Diplomatic Engagement

Australia can strengthen its diplomatic presence through regular and ongoing dialogue, utilising comprehensive partnerships to discuss key issues on reducing barriers and working towards structured intelligence sharing to enhance maritime security. Strategic and comprehensive partnerships can be used as a mechanism to engage in technical discussions on information sharing, and encourage strategic discussions on regional trends as a way to build trust.

The Australian Government’s appointment of an ASEAN special envoy to deepen Australia’s engagement with Southeast Asia will be accompanied by the development of a trade and economic strategy for the region. As the busiest maritime area in the world, maritime security must be a key part of any trade and economic strategy with Southeast Asia.

An Australian Maritime Security Strategy

Australia should articulate its priorities in the region through a clearly articulated national maritime security strategy for the Indo-Pacific. The strategy would be a valuable way for Australia to set out its national interest for a joint maritime security agenda with ASEAN countries. Australia’s approach to the region will be more convincing when articulated as an important national interest for Australia, steering away from the donor-recipient model, where Australia clearly states what it wants to achieve and where it can assist. A publicly declared maritime security strategy will provide an overarching framework to bring the Australian Government together, and also be an important element of transparency for Australia’s relationships with the region.

Australia’s maritime strategy could be communicated through a speech by the Minister for Foreign Affairs, a statement to Parliament, or an independently released maritime security strategy. In addition, regular engagement and ongoing communication between key military and government counterparts will remain a vital avenue for Australia to communicate its maritime security priorities. The goal is to express a whole-of-government vision of Australia’s maritime security strategy and foster a coherent interdepartmental approach on maritime security challenges in the region. There are challenges, and to achieve this would take strong leadership and would have to be fully implemented to justify the resources required to undertake the development of the strategy.

Supporting Emerging Australian and ASEAN Maritime Security Leaders

Australia must take a long-term generational approach to maritime security issues and support youth engagement as a way to use soft diplomacy to train the next generation of ASEAN and Australian leaders, foster cooperation, and develop innovative security strategies. The recent Australian Youth National Security Strategy (YNSS) project engaged young people through a series of workshops, research and policy development discussions to set out an alternative vision for Australian security. A similar project could be undertaken to connect ASEAN and Australian youth, and support the development of an ASEAN Youth National Security Strategy to encourage meaningful participation in maritime security discourse.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s successful ASEAN-Australian emerging leaders’ program (A2ELP), which brings together social entrepreneurs from Australia and ASEAN member nations, could be expanded – and could be given a maritime security focus in one of the years in which it is held. The program can be extended to encompass government, defence, local, civil and legal groups and universities to ensure that every level of government and civil society is represented.

Case Study: Australia Awards Scholarship Program

The Australia Awards scholarship program, managed by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, provides opportunities for people from developing countries to undertake full-time undergraduate or postgraduate study at participating Australian universities and Technical and Further Education institutions.

Australia Awards not only develop skills and knowledge of individuals, but strengthen links between people and organisations to enhance mutual understanding and cooperation. Recipients of Australia Awards become part of the Australia Global Alumni, further strengthening connections between Australia and the region.

This valuable and highly respected program is in demand across the region, and could be used to further education and training on maritime security issues.

Case Study: ASEAN Women, Peace, and Security Agenda

ASEANS’s Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) Agenda recognises that supporting women’s voices and leadership is key to sustaining peace, stability and development in the region. Key pillars of the Agenda are protection, participation, prevention, and relief and recovery.

ASEAN’s recently released Regional Plan of Action on Women, Peace, and Security aims to implement the WPS agenda to promote sustainable peace and security for all citizens. The development of the plan engaged ASEAN Sectoral Bodies overseeing regional cooperation on gender equality and women empowerment, defence, transnational crime, human rights, disaster management and humanitarian assistance.

Contributors

Thank you to those who have contributed their thoughts during the development of this paper. Views expressed cannot be attributed to any individuals or organisations involved in the process.

Abdul Rahman Yaacob

National Security College

Andrew Chubb

Lancaster University

Aristyo Rizka Darmawan

Universitas Indonesia

Bich Tran

Center for Strategic and International Studies

Bong Chansambath

Asian Vision Institute

Charmaine Willoughby

De La Salle University

Damian Spruce

Caritas Australia

Douglas Guilfoyle

University of New South Wales Canberra

Elise Stephenson

Australian National University

Emma Palmer

Griffith University

Fiona Tarpey

Australian Red Cross

Gary Quinlan

Former Ambassador

Jane Haycock

International Development Contractors Community

John Blaxland

ANU Strategic and Defence Studies Centre

Julio Amador

Amador Research Services

Kate Clayton

La Trobe Asia

Kris Kathiravel

Independent Consultant

Paul Sigar

ASEAN-Australia Strategic Youth Partnership

Renato Cruz De Castro

De La Salle University

Sharon Cowden

Former Australian Federal Police

Simon Henderson

Save the Children Australia

Sumathy Permal

Maritime Institute of Malaysia

Susannah Patton

Lowy Institute

Teesta Prakash

Australian Strategic Policy Institute

Thomas Daniel

Institute of Strategic & International Studies Malaysia

Thu Nguyen

European University Institute

William Stoltz

National Security College

Editors

About Blue Security

This is the first paper in a new Blue Security collaboration between AP4D, La Trobe Asia, Griffith Asia Institute, University of New South Wales Canberra Maritime Security Research Group and the University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute.

Funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Blue Security Program engages with and facilitates high quality research on issues of critical maritime security across the Indo-Pacific. Bringing together leading regional experts in politics, international law and strategic studies, Blue Security focuses on three key pillars of maritime security – order, law and power – and produces working papers, commentaries, and scholarly publications for audiences across the Indo-Pacific.

Visit the Blue Security website to learn more.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons license. You can reprint or republish with attribution.

You can cite this paper as: Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue, What does it look like for Australia and Southeast Asia to Develop a Joint Agenda for Maritime Security (Blue Security Consortium, 2023): www.asiapacific4d.com

Photo on this page: Alex Dukhanov, ‘Calm wave of ocean’ used under Creative Commons