What does it look like for Australia to be a...

Partner for Infrastructure with the Pacific and Southeast Asia

Published: September 2023

Executive Summary

Across Southeast Asia and the Pacific, infrastructure can be a vital enabler of economic and social development and growth, as well as supporting regional security. Australia’s development and defence policies both note the important role of infrastructure partnerships.

Australia currently invests in infrastructure bilaterally through mechanisms including grants, concessional and non-concessional loans, securities and various capacity-building and project preparation services. It also contributes finance to multilateral development banks, including the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank.

Australia’s development, diplomacy and defence communities agree that high quality infrastructure should be an important pillar of Australia’s partnerships within the region. However, each sector has a distinct idea of why infrastructure is important. Australia also needs to recognise the real limits on its resources, with current estimates for the region’s infrastructure requirements at around $1 billion for the Pacific and $92 billion for Southeast Asia.

Australia needs constantly to consider how its approach to infrastructure can:

- be well-targeted to partner countries’ needs and priorities;

- leverage Australia’s strengths in line with its limited resources; and

- have clarity on what success looks like in terms of Australia’s various development, diplomacy and defence objectives.

There is a basis for a whole-of-government approach to be built around some shared propositions:

- the region has significant infrastructure needs and that governments in the region are looking to actors such as Australia to help them meet those needs

- Australia can and should play a role in helping the region meet its infrastructure needs and that in doing so, this will be in Australia’s national interest. Australia has advantages and assets to contribute to the region’s needs

- Australian contributions to regional infrastructure needs should be responsive to the needs of Pacific and Southeast Asian countries and be delivered in partnership with those countries

- infrastructure is a domain for strategic competition in the region that affects Australia’s interests

- infrastructure can have broader spillover effects, especially in terms of social and economic development, reputation and generating influence

In a spirit of promoting debate, this paper sets out high-level principles on how Australia should approach partnering with regional countries on infrastructure.

The long-term vision is for Australia to have a clear sense of what its own interests are and to partner effectively with Pacific and Southeast Asian countries on infrastructure that is driven by their needs and helps them realise economic growth, human development, security and stability.

Australia’s interests are best served by strengthening relationships through working in partnership with both donor and recipient countries throughout the region to ensure investments in infrastructure are relevant, impactful and contribute to the political, social and strategic goals that Australia seeks. Across Southeast Asia and the Pacific, infrastructure can be a vital enabler of economic and social development and growth, as well as supporting regional security. Australia’s development and defence policies both note the important role of infrastructure partnerships.

What do we mean by ‘infrastructure’?

For the purposes of this options paper, the term ‘infrastructure’ is used to refer to physical assets and services, including (but not limited to) buildings and structures, energy and electrical, water and sanitation, transport, communications, maritime and security.

Where a broader conception of infrastructure is used, such as social infrastructure, this is explicitly stated. We define ‘social infrastructure’ as “the facilities, spaces, services and networks that support the quality of life and wellbeing of…communities,” including: health and aged care, education, recreation, arts and culture, social housing, justice and emergency services.

Social infrastructure initiatives enhance and complement either new or existing infrastructure. Cash payments or voucher programs, for instance, can be knitted together to form the basis for universal social protection systems, leveraging the improved connectivity that physical infrastructure generates to scale up national social welfare programs. Thinking about infrastructure in this holistic way – incorporating social and physical infrastructure together – could help diminish zero-sum calculations about investments of Australia’s development resources.

Small-scale initiatives in the Pacific have generated evidence that cash and voucher assistance is fast, effective and reliable. In countries without a formal safety net, these payments have been proven to give families in crisis the flexibility to help themselves in a dignified way.

Why it Matters

Australia has a compelling interest in seeing strong growth and prosperity in its near region: the Pacific and Southeast Asia. Supporting our partners in the delivery of high-quality infrastructure – a vital enabler for economic and social development and growth, as well as security – must therefore be a critical pillar of Australia’s foreign policy.

Infrastructure that addresses and responds to the needs and priorities of local communities, stakeholders and governments provides opportunities for relationship building and strengthening of national capabilities. Upgrades to connectivity and communication through transport and telecommunications, as well as enhancements to health, education, and governance structures, can provide the platform from which countries can advance their goals and allow their societies to flourish.

These essential building-blocks remain in great need throughout Australia’s neighbourhood. The cost of addressing the current infrastructure gap in the Pacific is 6.2 percent of the region’s gross domestic product (GDP), while in Southeast Asia it is 3.2 percent of GDP. In dollar terms, this is approximately $1 billion worth of investment in the Pacific and $92 billion in Southeast Asia. These considerable requirements are made more difficult by the susceptibility of both these regions to the effects of climate change.

The infrastructure needs of these two regions are diverse. In Southeast Asia, economies are larger and more attractive to private investment. Hurdles to meeting this region’s infrastructure needs are primarily at the project development stage, including the policy and regulatory architecture for project approval, governance problems, and project preparation capacity. In the smaller economies of the Pacific, meanwhile, infrastructure is more about providing basic services, with private investment difficult to attract given the challenges of remoteness and scale. Pacific governments will continue to face severe fiscal constraints in the wake of COVID-19, while also dealing with problems of debt sustainability, inadequate technical capability, and attracting sufficient external finance.

As we look to deepen and strengthen our relationships, we will offer an international development program that is based on partner priorities, is transparent in its approach, is not transactional in nature, is high quality, and prioritises local leadership, job opportunities and procurement."

Australia does not have the financial, technical, or operational resources to assist with all of the region’s infrastructure needs itself – but it has an important role to play in consultation with its partner countries to assess their requirements and provide an array of supports, including development finance and capacity building. While countries in the Pacific and Southeast Asia determine their own infrastructure needs, Australia will need to be astute and informed regarding its own decisions related to the nature and extent of development investment and other assistance it provides.

Supporting regional infrastructure development is also an investment in Australia’s future. Enhanced regional prosperity presents Australia with enormous opportunities to access new markets and consolidate bilateral relationships. Investment in neighbours’ development also builds the bonds of trust and habits of cooperation that will strengthen regional security.

At the same time, infrastructure has become a domain for strategic competition. While this has helped fuel greater investment in the region, it also presents risks in terms of how infrastructure investments are made and delivered. While some countries may welcome the greater attention that comes from strategic competition – and have become adept at leveraging this to their advantage – other countries, are more wary of being caught up in a contest of powers. In this, Australia’s influence is reliant on constructive and genuine relationships with regional governments and civil society that can produce positive development outcomes.

Australia’s interests are best served by working in partnership with both donor and recipient countries throughout the region to ensure its investments in infrastructure are relevant, impactful, and contribute to prosperity and stability. Although there is a narrow consensus both within and between the development, diplomacy, and defence communities about what this should entail precisely, there is a pressing need to establish a whole-of-government approach that will help Australia understand and be responsive to partner countries’ needs. This will ensure that Australia provides the most effective form of support for its neighbours in infrastructure design and delivery which will, in turn, realise the developmental and strategic outcomes it seeks.

Australia also contributes finance to multilateral development banks (MDBs), including the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank. These organisations are designed to assess infrastructure on a needs-based criteria and are explicitly set up to manage external risks that affect complex multi-financed projects. Australia’s new International Development Policy and Development Finance Review contain strong commitments to working with and through MDBs and international financial institutions. Improving how Australia influences MDBs should be part of these commitments. While Australia’s funding of MDBs is a significant element of its contribution to regional infrastructure, this report focuses on Australia’s bilateral infrastructure partnerships and investments.

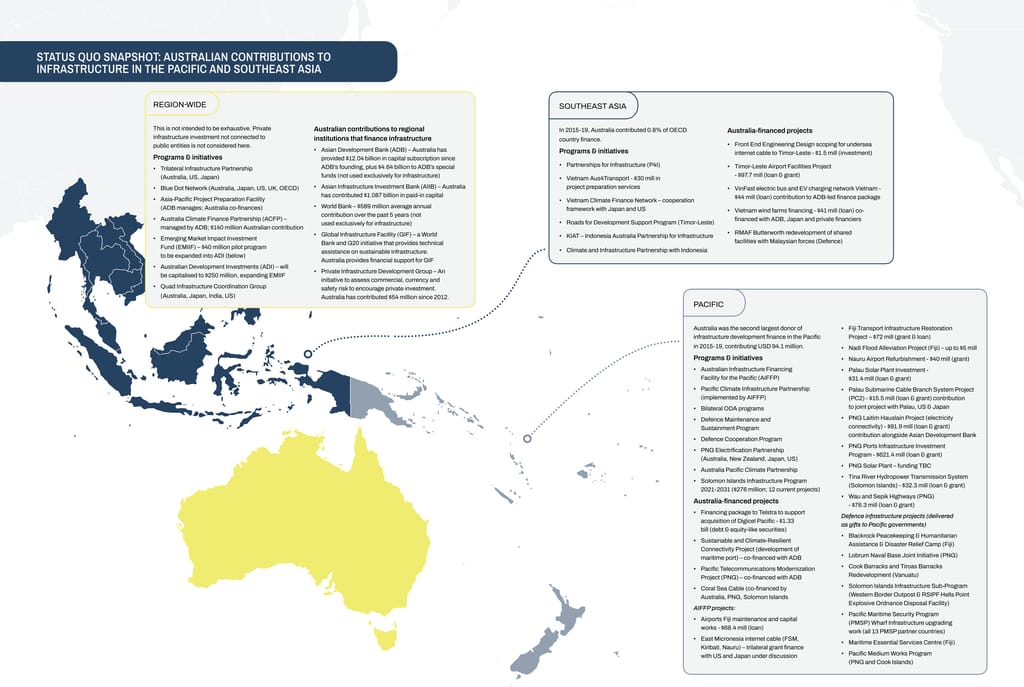

Status Quo Snapshot

Australia uses multiple different mechanisms and means to contribute to meeting regional infrastructure needs. It provides grants and loans (both concessional and non-concessional), as well as utilising other financial instruments such as securities. It also finances or provides various forms of capacity-building and project preparation services. Some of this is financed from official development assistance (ODA), but not exclusively. Australia also makes contributions to multilateral development banks (MDBs) that finance infrastructure in the region.

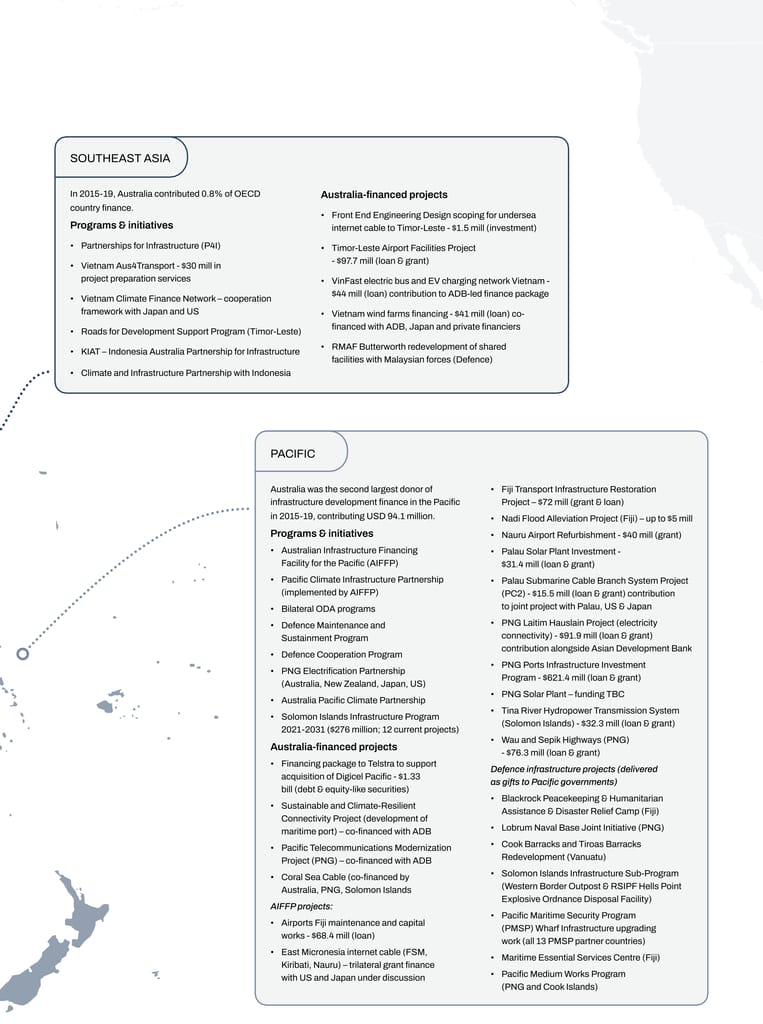

In 2015-19, Australia contributed 0.8% of OECD country finance to the region.

Programs & initiatives

- Partnerships for Infrastructure (P4I)

- Vietnam Aus4Transport - $30 mill in project preparation services

- Vietnam Climate Finance Network – cooperation framework with Japan and US

- Roads for Development Support Program (Timor-Leste)

- KIAT – Indonesia Australia Partnership for Infrastructure

- Climate and Infrastructure Partnership with Indonesia

Australia-financed projects

- Front End Engineering Design scoping for undersea internet cable to Timor-Leste - $1.5 mill (investment)

- Timor-Leste Airport Facilities Project - $97.7 mill (loan & grant)

- VinFast electric bus and EV charging network Vietnam - $44 mill (loan) contribution to ADB-led finance package

- Vietnam wind farms financing - $41 mill (loan) cofinanced with ADB, Japan and private financiers

- RMAF Butterworth redevelopment of shared facilities with Malaysian forces (Defence)

This is not intended to be exhaustive. Private infrastructure investment not connected to public entities is not considered here.

Programs & initiatives

- Trilateral Infrastructure Partnership (Australia, US, Japan)

- Blue Dot Network (Australia, Japan, US, UK, OECD)

- Asia-Pacific Project Preparation Facility (ADB manages; Australia co-finances)

- Australia Climate Finance Partnership (ACFP) – managed by ADB; $140 million Australian contribution

- Emerging Market Impact Investment Fund (EMIIF) – $40 million pilot program to be expanded into ADI (below)

- Australian Development Investments (ADI) – will be capitalised to $250 million, expanding EMIIF

- Quad Infrastructure Coordination Group (Australia, Japan, India, US)

Australian contributions to regional institutions that finance infrastructure

- Asian Development Bank (ADB) – Australia has provided $12.04 billion in capital subscription since ADB’s founding, plus $4.64 billion to ADB’s special funds (not used exclusively for infrastructure)

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – Australia has contributed $1.087 billion in paid-in capital

- World Bank – $589 million average annual contribution over the past 5 years (not used exclusively for infrastructure)

- Global Infrastructure Facility (GIF) – a World Bank and G20 initiative that provides technical assistance on sustainable infrastructure. Australia provides financial support for GIF

- Private Infrastructure Development Group – An initiative to assess commercial, currency and safety risk to encourage private investment. Australia has contributed $54 million since 2012.

Australia was the second largest donor of infrastructure development finance in the Pacific in 2015-19, contributing USD 94.1 million.

Programs & initiatives

- Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP)

- Pacific Climate Infrastructure Partnership (implemented by AIFFP)

- Bilateral ODA programs

- Defence Maintenance and Sustainment Program

- Defence Cooperation Program

- PNG Electrification Partnership (Australia, New Zealand, Japan, US)

- Australia Pacific Climate Partnership

- Solomon Islands Infrastructure Program 2021-2031 ($276 million; 12 current projects)

Australia-financed projects

- Financing package to Telstra to support acquisition of Digicel Pacific - $1.33 bill (debt & equity-like securities)

- Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Connectivity Project (development of maritime port) – co-financed with ADB

- Pacific Telecommunications Modernization Project (PNG) – co-financed with ADB

- Coral Sea Cable (co-financed by Australia, PNG, Solomon Islands

AIFFP projects:

- Airports Fiji maintenance and capital works - $68.4 mill (loan)

- East Micronesia internet cable (FSM, Kiribati, Nauru) – trilateral grant finance with US and Japan under discussion

- Fiji Transport Infrastructure Restoration Project – $72 mill (grant & loan)

- Nadi Flood Alleviation Project (Fiji) – up to $5 mill

- Nauru Airport Refurbishment - $40 mill (grant)

- Palau Solar Plant Investment - $31.4 mill (loan & grant)

- Palau Submarine Cable Branch System Project (PC2) - $15.5 mill (loan & grant) contribution to joint project with Palau, US & Japan

- PNG Laitim Hauslain Project (electricity connectivity) - $91.9 mill (loan & grant) contribution alongside Asian Development Bank

- PNG Ports Infrastructure Investment Program - $621.4 mill (loan & grant)

- PNG Solar Plant – funding TBC

- Tina River Hydropower Transmission System (Solomon Islands) - $32.3 mill (loan & grant)

- Wau and Sepik Highways (PNG) - $76.3 mill (loan & grant)

Defence infrastructure projects (delivered as gifts to Pacific governments)

- Blackrock Peacekeeping & Humanitarian Assistance & Disaster Relief Camp (Fiji)

- Lobrum Naval Base Joint Initiative (PNG) • Cook Barracks and Tiroas Barracks Redevelopment (Vanuatu)

- Solomon Islands Infrastructure Sub-Program (Western Border Outpost & RSIPF Hells Point Explosive Ordnance Disposal Facility)

- Pacific Maritime Security Program (PMSP) Wharf Infrastructure upgrading work (all 13 PMSP partner countries)

- Maritime Essential Services Centre (Fiji)

- Pacific Medium Works Program (PNG and Cook Islands)

Case Studies

The Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP) became operational in mid-2019 as part of the Australian Government’s Pacific Step-Up. Its purpose is to support the development of high-quality infrastructure in the Pacific and Timor-Leste through concessional finance, including loans and grants. AIFFP has $4 billion in finance: $3 billion in loans plus $1 billion in grants.

AIFFP currently has 14 approved projects across Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Federated States of Micronesia, Timor-Leste, Palau, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands.

It provides a flexible financing approach on a project-by-project basis. It uses a mixture of grant and loan-based finance.

AIFFP investments are driven by a set of principles for planning, assessing and financing projects: responsiveness to needs of partners; transformation (whether the project contributes to positive change in Pacific); responsible lending (debt sustainability); safeguards (for environment, children, vulnerable groups, displacement, indigenous people, and workplace health and safety); local content; climate resilience; equality and inclusion; high technical quality; risk management; and transparency. These principles reflect the inherent difficulties and risks of providing infrastructure in the Pacific.

AIFFP represents Australia’s most comprehensive infrastructure offering to the region, providing finance alongside project management.

The AIFFP Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Plan outlines how infrastructure investments are assessed for their quality, development outcomes and intended results. The Two-Year System-Wide Review of AIFFP conducted in late 2022 and response explain AIFFP’s progress and likely areas for growth and improvement.

Partnerships for Infrastructure (P4I) is an Australian Government initiative to partner with Southeast Asian countries to help deliver quality infrastructure for the region.

The primary focus of P4I is technical assistance: to provide capabilities and expertise in policy and regulation, prioritisation, planning and procurement. Within the P4I’s mission is the advancement of green technology throughout the region.

P4I brings together five distinct organisations with complementary expertise: DFAT, The Asia Foundation, EY, Adam Smith International and Indigenous professional services company Ninti One.

The model of providing services, advice and connections to Southeast Asian governments to help them make and manage infrastructure investments demonstrates how Australia can play a niche, capacity-building role in contexts where that is best aligned with Australia’s advantages.

Australia’s Department of Defence partnered with the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) to redevelop the Blackrock Camp as a major training facility for Fiji’s armed forces.

The $100 million investment included a new headquarters building; front entrance and guard house; logistics precinct (including humanitarian assistance and disaster relief warehouse); as well as lecture/classroom facilities; medical facility; living-in accommodation; sports field; physical training facilities; and parade ground.

The facility was designed to be a regional training hub for other security forces throughout the Pacific.

With the effects of climate change a major security priority for the Pacific, Blackrock’s focus on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief reflects Australia’s sharing of these concerns.

Blackrock was recently used as a staging ground for the deployment of RFMF to Vanuatu as part of the humanitarian response following the 2023 cyclones.

Financing for Electric Buses and Wind Farms (Vietnam)

The project will also provide women from the local community with access to training on wind power operation and management, under a plan to upskill local women.

In conjunction with the Australia Climate Finance Partnership, EFA has provided USD30 million towards this investment, almost a quarter of the total package.

Both projects demonstrate Australia making strategic contributions as part of a larger consortium to support commercial projects in Southeast Asia.

Solomon Islands Infrastructure Program (SIIP) is an $276 million partnership between Australia Solomon Islands to build a large pipelines of economic infrastructure projects.

Running 2021 to 2031, SIIP has two goals:

- Enhance the capacity of government and the private sector to plan, manage, finance, construct and/or maintain critical infrastructure

- Deliver resilient, accessible infrastructure assets across the country that support inclusive economic growth.

SIIP aims to deliver four outcomes for Solomon Islands:

- Finance: Greater access to international infrastructure finance

- Planning: Improved planning and policy settings to support inclusive, quality infrastructure

- Construction: Construction of high quality, priority infrastructure

- Capacity: Improved skills and capacity to plan, build and maintain quality infrastructure.

Twelve projects are currently being delivered under SIIP:

- Bina Harbour Project ($0.7 million)

- Buala Market Redevelopment ($3.3 million)

- Buala Wharf Redevelopment ($11.8 million)

- Gizo Water Supply Project ($10 million SIIP contribution)

- Honiara Central Market Expansion ($1 million SIIP contribution)

- Malu’u Market Redevelopment ($3.3 million)

- Naha Birthing and Urban Health Centre ($27 million)

- Noro Port Redevelopment ($1.5 million)

- Seghe Airport Upgrade ($23.15 million)

- Seghe Market Redevelopment ($3.3 million)

- Taro Airport Upgrade ($23.15 million)

- Industry Capacity Development

SIIP is an example of a comprehensive bilateral infrastructure partnership that provides finance for building infrastructure projects of high quality, as well as broader capacity-building support and efforts to increase access to broader pools of international finance.

The Thai-Laos Friendship Bridge was the first major bridge across the lower Mekong, linking the town of Nong Khai in Thailand with the capital of Laos, Vientiane. Australia provided $42 million in aid to fund feasibility studies, design and construction of the bridge between 1991 and 1994.

Since its opening, the bridge has helped stimulate trade, tourism, investment, cultural exchanges, transportation and logistics. In doing so, the bridge has become an enduring symbol of friendship and cooperation between Australia, Thailand and Laos.

The enduring soft power and reputational benefits Australia continues to enjoy from the bridge demonstrates the long-term positive impacts that meaningful infrastructure investments can have.

The Roads for Development Support Program (R4D-SP) began in March 2012. R4D-SP was the Government of Timor-Leste’s leading rural roads program, implemented by the Ministry of Public Works, to improve the management and condition of Timor-Leste’s rural road network.

The Australian development program provided technical assistance through the International Labour Organization (ILO) with Phase I totalling $36 million 2012-2017 and Phase II up to $26 million 2017- 2021.

The overall goal of Australia’s R4D-SP was for women and men in rural Timor-Leste to derive social and economic benefits from improved road access.

Australia funded the construction of a 4,700km submarine internet cable linking Sydney with Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. After 18 months of construction the cable was completed in December 2019. The project to build the cable also included the construction of a domestic network in Solomon Islands linking Honiara with Auki, Noro and Taro Island.

The cable is an important upgrade in internet and date connectivity for both Solomon Islands and PNG. Previously they relied on outdated cables and satellite technology. The purpose of the cable is to deliver faster, cheaper and more reliable communications infrastructure to generate economic and development benefits for both PNG and Solomon Islands.

Australia funded most of the cable costs, with smaller contributions from PNG and Solomon Islands. The Cable system is run by the Coral Sea Cable Company, which is equally owned by the Australian Government, PNG DataCo and the Solomon Islands Submarine Cable Company.

Digital Cash Programming in Fiji

Small-scale social infrastructure initiatives in the Pacific have generated evidence that cash and voucher assistance is fast, effective and reliable. In countries without a formal safety net, these payments have been proven to give families in crisis the flexibility to help themselves in a dignified way. Investment at such a significant scale should be underpinned by evidence and proof of concept trials.

With support from Disaster READY under the Australian Humanitarian Partnership, Save the Children has already built and tested cash and voucher delivery mechanisms across the Pacific. 30,022 people in Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Fiji and Papua New Guinea benefited from this assistance between 2017 and 2022. This work was scaled in Fiji to distribute $20 million USD to over 39,000 families impacted by the pandemic. Such an investment could build on the system-level work undertaken by the Australian Government-funded Partnerships for Social Protection.

Using assessment criteria developed with the Fijian government and local NGOs like the Fiji Council of Social Services, Save the Children prioritised vulnerable groups such as the elderly, women, children and people living with a disability. Save the Children uses cash and voucher assistance to support households impacted by disasters all over the world, however the use of digital cash is a recent development.

While cash and voucher assistance can help Pacific families meet their basic needs in a dignified way, they are not a ‘silver bullet’ for alleviating all aspects of poverty. There is compelling evidence that cash transfers can achieve significantly greater impacts on child outcomes when combined with complementary interventions and other services that physical infrastructure upgrades that boost connectivity.

Perspectives on Infrastructure

For Australia to build trusted and respectful partnerships with its Pacific and Southeast Asia partners for the delivery of infrastructure, it must first understand how its own constituencies and policy actors think about, understand, and evaluate infrastructure outcomes. This has been an area of ongoing debate within Australia’s policymaking circles, centred around fundamental questions of ‘whether’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ Australia should contribute to the region’s infrastructure needs.

The interactive below sets out some views on infrastructure that are common across differing sectors of Australian policy, demonstrating that each sector has distinct ideas about what should motivate our infrastructure contribution, which types of investments are important, and how they should be pursued. This account necessarily generalises perspectives and does not attempt to account for the diversity of views that exist within different sectors. It is intended as an analytical tool for researchers and policymakers to understand the various perspectives that influence infrastructure contributions by Australia.

The different perspectives outlined below indicate that there is a high degree of divergence between Australia’s policy communities on infrastructure – in particular, on fundamental questions of what considerations should motivate Australia’s bilateral investments. Infrastructure is, therefore, one of the most internally contested elements of Australian statecraft. While differences in views are inevitable – and in some cases can be productive – such tension can also hinder coherent policy development and implementation. Teasing out different perspectives and recognising key points of divergence is the starting point for developing a more cohesive policy approach.

Infrastructure investments sit within the broader context of bilateral and regional partnerships that Australia seeks to nurture and maintain, and alongside Australia’s geopolitical interests – both having short- and long-term considerations.

Building infrastructure in the region, or supporting regional countries to do so, has two related goals for Australia:

- Contributing to a more stable and prosperous region that is favourable to Australian interests.

- Being regarded as a partner of choice to regional countries by helping meet their infrastructure needs, thereby boosting Australia’s influence and prestige. This is the case for both access to (and influence with) elites and broader positive perceptions.

Australia’s capacity to provide infrastructure and support for infrastructure is also an important reputational consideration. Not only are Australia’s offerings judged on their own merits, but they are also measured against those of other actors. How Australia compares to China is especially important.

The provision of infrastructure by Australia can also be a means to deny the opportunity for others to do so. Investments by Australia in telecommunications infrastructure in the Pacific (such as the Coral Sea Cable or Telstra’s acquisition of Digicel) can be understood as preventing such critical assets being built or acquired by adversaries or competitors and, potentially, used for intelligence gathering.

Infrastructure is regarded as a key international engagement opportunity for defence by addressing shared security challenges and enhancing the capacity of regional partners to meet their own security needs, especially in the Pacific. Building and providing security infrastructure allows Australia to strengthen security partnerships and build greater interoperability with defence and law enforcement counterparts. Training, education, personal connections and regional knowledge and experience are seen as clear benefits flowing from infrastructure initiatives.

Infrastructure is also seen as an important enabling factor for the security of Australia and partner countries. Physical assets such as barracks and wharves help provide the means for the ADF and the forces of partner countries to respond to threats and crises, such as humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations.

Infrastructure is also seen as an important vector for strategic competition and malign influence by adversaries. There is concern over the ‘dual use’ of notionally civilian infrastructure by adversaries to project force in Australia’s region, as well as the provision and maintenance of infrastructure being used by competitors as a means to secure an ongoing presence in the region.

Strategic calculations regarding infrastructure can force decisions regarding certain investments to be made in short timeframes – especially when there is a perceived need to deny the opportunity for an adversary or competitor to provide the same infrastructure. While such decisions may be necessary in the circumstances, they can generate trade-offs in terms of building partnerships with regional neighbours and being able to make longer-term investments elsewhere.

Meeting immediate infrastructure needs also requires a high degree of flexibility and the capability to work with clear focus and intent. Presently Australia’s relative lack of speed and scale is a limitation.

There is a spectrum of views on infrastructure within the development sector, in particular amongst NGOs and economists. However, an important starting point is a recognition that people in developing countries deserve and need good infrastructure.

Infrastructure sits within the broader context of Australia’s limited development resources and the need to prioritise investments. This means Australia should focus on where it can generate the greatest human development impact, considering the needs of partner countries and Australia’s own capacities and advantages.

This can include infrastructure, but this might not always be the priority relative to the other needs of regional countries and Australia’s ability to provide effective solutions. The opportunity costs of focusing on infrastructure need to be carefully considered, especially vis-à-vis other means to alleviate poverty that may be more direct.

There is a concern that both the overall focus on physical infrastructure and individual project or investment decisions are primarily motivated by responding to strategic competition with China in the region. This can come at a cost to meeting the most pressing needs of the region with the limited development resources Australia has.

At the same time, recognising that states legitimately pursue their security interests, including through infrastructure, Australian interests will be best served by contributing to infrastructure that meets the real needs of partner countries and that conforms to robust safeguards.

Infrastructure investment should therefore proceed in accordance with coherent national plans developed by national governments, potentially with Australian advice and support. This may mean focusing more on fundamental human necessities that are the building blocks of prosperous societies, including the provision of water, electricity and sanitation, climate resilience, alongside quality health and education.

There is also a belief that Australia should not seek to compete on larger scale projects that more well-resourced actors are better placed to take on. Instead, Australia should focus on the aspects of infrastructure development where it can have a greater impact, for instance capacity-building for regional governments.

Like all government decisions, Australia’s contributions to regional infrastructure sit within the broader context of public finances, annual budget process and accountability mechanisms. The significant financial undertakings that infrastructure often demands – whether as a grant, loan or other financial instrument – means that fiscal constraints, as well as risk assessment and management, are key considerations.

The development, diplomacy or defence case for infrastructure investments need to be weighed against the financial risks, considering factors such as lending rates and risk of default. Moreover, any financial risk or exposure undertaken by the Australian Government needs to be justified by a clear evidence base and measures of success. However, given that regional infrastructure contributions are often motivated by subjective considerations such as strategic risk and relative international influence, it can be difficult to quantify the benefits to Australia. There are also trade-offs to be made between short-term and long-term objectives, public and private financing, and how to balance growth and equity as the intended consequences of investments.

Domestic political considerations are also important to consider. Infrastructure investments made by Australia overseas can be seen as an opportunity cost for money better spent in Australia (especially considering Australia’s significant infrastructure needs in areas such as transport). While in reality such trade-offs between domestic and foreign infrastructure investment are not so stark, they can be politically effective. Policymakers need to be vigilant about such considerations, understanding that their decisions will be scrutinised on this basis.

At the same time, however, there are potential points of consensus across Australia’s international policy community as to how

infrastructure can be used as a foundation for effective partnerships with the region.

Areas of potential consensus

- All sectors of Australian international policy understand and agree that the region has significant infrastructure needs and that regional governments are looking to actors such as Australia to help them meet those needs.

- There is a shared understanding that infrastructure is a domain for strategic competition in the region that affects Australia’s interests.

- There is agreement that Australia can and should play a role in helping the region meet its infrastructure needs and that doing so is in Australia’s national interest. Moreover, it is broadly understood Australia does have advantages and assets to contribute to the region’s needs.

- Any Australian contributions to regional infrastructure needs should be responsive to the needs of Pacific and Southeast Asian countries and be delivered in partnership with those countries.

- There is a shared recognition that infrastructure can have broader ranging influence and outcomes, especially in terms of social and economic development, reputation and generating influence.

- All stakeholders recognise that there is a need for coordination with other donor countries and multilateral banks to avoid duplication and strain on the limited bureaucratic capacity of many recipient countries.

Pacific Voices

AP4D presented a draft version of this report at the ANU Pacific Update in Fiji in June 2023. We have synthesised the views received from ten experts from across the Pacific on how Australia can best partner with the region on infrastructure.

In the Pacific there is a recognition that Australia lacks the resources and capabilities to assist with all the region’s infrastructure needs. However, what is desired from Pacific Island countries is relationships built on trust where Australia can use its capabilities to:

- help develop a holistic infrastructure plan for Pacific countries that takes into consideration their debt levels;

- assist negotiations alongside Pacific countries concerning loans with MDBs to help fund these plans; and

- supplement Pacific capacity to manage infrastructure projects when they come online.

A priority for Pacific Island countries is the technical aid that Australia can provide. Infrastructure investment should have a focus on building up the capabilities of local experts so that they can both maintain infrastructure and drive projects in the future. It is the transfer of skills more than the transfer of funds that is primarily desired. At present, Pacific companies find it difficult to win tenders from MDBs for infrastructure projects. Therefore, Australia prioritising the involvement of Pacific companies with its own investments could help make these companies more attractive to other investors.

To achieve this, Pacific Islanders should be included in the full lifecycle of projects. This uplifts local capabilities from scoping through to delivery, as well as ongoing maintenance.

Pacific Island countries are aware of their own requirements and can drive the strategic calculations for their own national development. The challenge is finding the financing for their identified projects, and especially financing that avoids generating unsustainable debt burdens. Part of this problem is that private sector actors do not foresee great returns throughout the region, so there is a need for more blended financing, and for governments to help address market failures. Strong accountability measures are needed within both the financing of projects and their delivery.

Risks and Barriers

As Australia seeks to build partnerships for infrastructure with countries in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, it needs to account for the risks and barriers associated with meeting its neighbourhood’s needs. The requirements and operating environment for infrastructure investment not only vary greatly between these two regions, but also within them.

Outlined below are some of the risks and barriers associated with Australia’s own capacities and capabilities, the general risk factors in-country and the issues around coordination with other partners and financiers. These risks help inform the principles that Australia should adopt when building and sustaining infrastructure partnerships in the region.

Risks for Australia

What success looks like

A foundational risk for Australia’s approach to infrastructure lies in not having a clear sense of why it focuses on infrastructure and what it means for any one investment to be a ‘success’ for the national interest. Different elements in Australian statecraft approach infrastructure with different motivations and objectives in mind. While none of these are necessarily more important than another, the potential effectiveness of any one project or program may be compromised by not having a clear-sighted understanding of precisely what Australia is looking to achieve. This is especially true, for instance, for investments that are primarily motivated by foreign policy and strategic considerations, which may run the risk of being less closely aligned with achieving human development outcomes.

Australia is understandably reluctant to explicitly label any of its infrastructure investments as strategically motivated – this would be counterproductive to the influence dividend they are designed to generate. However, couching projects or initiatives purely in developmental terms when there are clearly other considerations at play means that the full picture is not entirely clear – either for Australia or partner countries. Development outcomes are often easier to measure, whereas goals such as political influence or strategic denial are inherently more subjective.

The Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP) theory of change attempts to grapple with such mixed imperatives, listing one of its outcomes as “Australia is a partner of choice for financing infrastructure in the Pacific”, alongside meeting the Pacific’s development needs and increasing the region’s access to capital. This outcome is measured against three indicators: AIFFP’s market share in Pacific infrastructure; regard for AIFFP financing by partner governments and non-sovereign borrowers; and perception about AIFFP investments in the Pacific. This demonstrates a clear intent to generate foreign policy outcomes related to influence and reputation, alongside development outcomes.

The ongoing, broader risk for Australia lies in not having a full-spectrum framework that encompasses all relevant perspectives on infrastructure – development, diplomacy, defence, and domestic accountability – that provides clarity around why decisions are being made and what outcomes are being sought.

Australia’s limited resources for investing in infrastructure

While both Southeast Asia and the Pacific have substantial infrastructure needs, Australia’s resources to address such needs are inherently limited as a function of the size of its economy and competing demands on government expenditure. With limited resources for infrastructure, every investment – whether in a specific project or a policy level decision to focus on infrastructure rather than something else – generates an opportunity cost. Having many imperatives but only very limited resources also generates the risk of fragmenting investments in a way that limits their effectiveness. This, in turn, may undermine the trust-based relationships Australia seeks to consolidate.

This is especially the case for infrastructure spending drawn from Australia’s overseas development assistance (ODA). Given that Australia has any number of other regional priorities and the dividends of infrastructure often take longer to realise, there is a significant risk inherent in any infrastructure decision where resources, especially ODA, might have been better spent elsewhere.

Australia’s relatively shallow pockets compared to other sovereign financiers operating in the region also means that any attempt by Australia to compete fully with other wealthier actors is futile and could result in resources being thinly spread and investments being less effective. As such, Australia needs to constantly consider how its approach to infrastructure can be well-targeted, leverage Australia’s strengths and direct them towards areas identified by local governments that will contribute to the greatest impact.

To create a more active and well-targeted approach to investment in Australia’s neighbourhood, a blunt assessment of Australia’s capabilities is required. Financial resources are only one factor in a complex array of considerations that limit Australia’s ability to invest in infrastructure. Australia is increasingly recognising that while it does have an important role providing finance and, in some cases managing specific programs of infrastructure related works (especially in the Pacific), it also has advantages in playing more limited or niche roles in infrastructure management, oversight and/or delivery. These can include making partial contributions to projects managed by other partners (including MDBs), capacity-building at both the technical and policy levels, supporting partner countries plan and manage their own infrastructure projects, and using alternate financial instruments to shift the risk calculus of private sector investors. The August 2023 Development Finance Review makes this clear. Partnerships for Infrastructure (P4I) is an example of Australia focusing on its advantage in capacity building to make an effective contribution in a region where finance is more abundant and competitive.

Reputational risks

Care needs to be taken to avoid the perception that decisions related to infrastructure investments are decided in Canberra and delivered with an eye towards Australia’s strategic calculations rather than stakeholder and local community requirements. While high-profile projects are very visible symbols of presence and commitment (for both donor and recipient nations), there are potential costs to bilateral relationships and to Australia’s reputation if projects are not developed through meaningful dialogue and collaboration with local actors or if they are not delivered effectively. Smaller scale projects, while less conspicuous, can also produce significant reputational dividends; sanitation systems, for instance. Moreover, projects that are seen to be initiated at a distance are often also less effective in achieving local engagement and/or producing positive outcomes.

Reputational risk can also result due to comparison to other development partners. This is not only a calculation made in relation to China’s emergence as a major infrastructure investor in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, but also compared to allies and other donor countries that may have more effective approaches to their own development assistance programs. This may make Australia’s approach and investment offerings less attractive.

Being a responsible investor requires an awareness of what is affordable and manageable for partner countries. The August 2023 International Development Policy and Development Finance Review make clear that “[t]raditional grant-based financing through the Official Development Assistance program will no longer be enough to meet the development needs of our partners”, meaning that loans and other forms of development finance instruments will be increasingly used by Australia.

However, with high levels of debt already existing in the region, especially the Pacific, Australia needs to be careful not to worsen debt sustainability problems. Australia’s new International Development Policy states that “[p]ublic debt in the Pacific is expected to almost double by 2025, compared to 2019.” With interest rates rising, loans offered by Australia (especially by the AIFFP) may become less attractive to the region. Rising rates make debt burdens more difficult to manage. Critically, debt limits the ability for states to use their revenue streams for their domestic priorities. As a result, there is no walking away from grant finance, and the need for public accountability that accompanies the use of grant finance, as a critically important mode for making financial investments in the region.

Competitiveness

Safeguards, due diligence and high-quality standards can be difficult issues for Australia to navigate and include within the requirements of infrastructure investment offerings. Recipient countries may prioritise funders that require less stringent processes and evaluation outputs. Lowering standards may lead to poorer quality outcomes, however these need to be balanced with pragmatic delivery expectations so Australia does not place conditions on their investments that are too onerous. Australia is sometimes seen as slow, under-resourced, too bureaucratic, and less inclined to accept partner countries’ priorities without reservation.

By comparison, for instance, Japan is regarded by some as more practical and realistic, working with governments to ask what they would like with lower expectations in return. While problems exist with China’s approach to infrastructure delivery, resulting in varying degrees of quality in its infrastructure contributions, Chinese infrastructure investments tend to be implemented and completed at a far greater pace than Australia’s. At the same time, however, a hallmark of Australia’s approach must be the upholding of standards. The challenge for Australia, then, is to avoid compromising on quality while being as flexible as possible to respond to local needs. The new International Development Policy recognises this tension:

For instance, the establishment of the Blue Dot Network in 2019 as a joint initiative of Australia, the United States and Japan was designed to assess and certify development infrastructure projects using metrics of financial transparency, project quality, environmental sustainability, and positive economic impacts. Yet often these criteria are of such a high standard that Australia’s own domestic infrastructure would not gain approval. This initiative may have been established with good intentions, but instead risks adding an unnecessary layer of complexity and bureaucracy to infrastructure investments and duplicating the role of other actors such as credit ratings agencies. It remains unclear whether the Blue Dot Network has delivered on its intent.

These challenges also extend to regulatory conditions and standards, which add a further layer of complexity to delivering infrastructure. These include strong requirements around codes and standards, environmental safeguarding and gender monitoring. These regulations can achieve positive outcomes, but can be difficult to explain to some local communities, especially when other donors may not have such regulations.

Australia’s domestic infrastructure priorities may create a shortage of skills required to spearhead infrastructure projects overseas. Added to this is the difficulty and cost in sending people overseas. Often the regions with the greatest infrastructure needs are the most remote and inaccessible.

In-country Limitations and Risks

The restraints on accessing and deploying Australian skills can be further complicated by a scarcity of local labour. Small local populations and economies, as found in the Pacific, can make local labour, and therefore capacity development opportunities, difficult to secure. Furthermore, one of the unintended consequences of Australia’s Pacific Labour Scheme is that it reduces the supply of skilled labour available within Pacific countries to be hired for local infrastructure projects.

The scarcity of labour is also mirrored by the scarcity of materials. The COVID-19 pandemic created a major disruption in supply chains from which the world is still recovering. Alongside this, new geoeconomic strategies driven by the United States that seek to decouple certain industries from China may also disrupt the availability and distribution of materials. This is particularly relevant to critical minerals that emerging green technology like lithium batteries is reliant upon, as well as the production of solar panels that China currently dominates.

Beyond this, there should also be recognition that facility management, maintenance and general operations for infrastructure will usually fall on the public sector and local ministries (often using private contractors. Many partner countries may not have the necessary financial resources or technical expertise to dedicate to these investments for maintenance. Effective ongoing maintenance often relies on an investment in upskilling local populations, which should be seen as an essential component of any infrastructure investment. Defence’s approach to infrastructure, especially through the Defence Maintenance and Sustainment Program, is an example of building these considerations into infrastructure policy.

Any kind of significant investment attracts risks of corruption; infrastructure is no exception. Working with partner countries, Australia needs to be vigilant to managing corruption risks at all stages of a project, program, or initiative. In particular, corruption risks at the pre-contract stage in how and why particular projects are selected or nominated need to be carefully monitored. Australia contributing inadvertently to corrupt political dynamics will only serve to undermine the effectiveness of its investments in terms of social and economic outcomes as well as perceptions. Consequently, Australia must place a high premium on transparency in both its own infrastructure decision-making processes (including in its use of contractors and consultants), but also those of its partner countries. Even the perception of corruption can undermine the efficacy of an investment.

Australia must also be cognisant of broader political risks associated with supporting infrastructure overseas given how such investments can work within local partisan dynamics that can be difficult for outsiders to fully grasp. This is a particular risk for physical infrastructure given its tendency to be used to gain a political advantage.

Local infrastructure needs, as expressed by elites, will not always reflect the actual requirements of local communities. While engagement with those currently holding power is inevitable, Australia must be careful to not prioritise meeting elite preferences to sustain influence over building sustainable partnerships with countries to support their development – independent of who may be in power at any one time. Australia, too, should be careful that its own domestic political debates do not exert an outsized influence on its infrastructure investment decisions.

A related risk for Australia in working with local leaders is in their level of commitment to upholding rigorous standards around the development and maintenance of infrastructure. Rhetorical commitments to human rights and other safeguards measures, including against modern slavery, need to be matched with substantive steps. The long-term sustainability of Australia’s partnerships would be put in jeopardy by failing to manage these risks.

Coordination of Infrastructure and Crowding in Development Finance

Given Australia’s limited resources and capabilities, it necessarily needs to work in partnerships with other donors and actors to deliver on significant infrastructure promises. The Trilateral Infrastructure Partnership with Japan and the United States is such an example. Engaging with multiple actors does, however, generate challenges in coordination. Countries and other actors, such as multilateral development banks, will have differing interests, worldviews, processes, languages, and ways of working which need to be harmonised, not only between infrastructure providers but also with host countries.

Fluctuating levels of commitment from partner countries can also make coordination difficult. This in turn can generate delays and reduce responsiveness to meeting partner countries’ needs. While it is desirable for Australia to leverage the resources and capabilities of others, it needs to be aware of the risks to project and program delivery that are created by involving more actors and seek to actively mitigate such risks. The difficulty in operationalising the PNG electrification partnership between Australia, New Zealand, the US and Japan can be at least partially attributed to such problems.

There are also broader coordination issues when multiple external actors are operating in parallel in the same country to meet infrastructure needs. Donors need to be in constant dialogue with partner countries and between each other to ensure their respective efforts are not duplicated or undermine each other. Ideally, respective contributions should be closely aligned and complementary to ensure that benefits derived from one project or program can help generate positive outcomes from others. For instance, aligning capacity-building and project preparation assistance provided by one actor with the particular demands of projects financed by another. This is especially important given the limited capacity of many smaller developing nations in the region – especially in the Pacific – to manage and direct contributions from multiple external providers.

Australia and other OECD donors also face the ongoing challenge of mobilising private investment to support the region’s infrastructure needs, whether that be through blended finance arrangements or wholly private investment. In the five years to 2020, an average of only USD 0.82 million per year of private infrastructure finance was mobilised in the Pacific by OECD governments, and only USD 132.6 million per year in Southeast Asia. Australia and others should continue to find ways to attract private (and potentially philanthropic) investment where possible to multiply the impact of public investments.

While the Blue Dot Network has an objective to mobilise private investment, this is no panacea. Due to small populations as well as distinct geographic challenges, mobilising private investment is difficult in the Pacific, as well as in outlying regions of Southeast Asia. There is a lack of bankable projects, high financial risks, low returns, and a lack of confidence in local policies and legal systems.

Development Finance Review

- In the Pacific, Australia should continue to focus on grant-based or concessional loan finance to support climate resilient infrastructure.

- While Australia will always be a relatively modest source of finance in Southeast Asia, it can achieve greater impact by adopting a more strategic and targeted approach to investment decisions, while also focusing on mobilising capital from other sources.

- Blended finance and technical assistance are identified as two key means for Australia to enhance its contribution, helping with project preparation and crowding in finance from other sources by shifting the risk calculus of private investors.

The Vision in Practice

What does it look like for Australia to be a partner for infrastructure with the Pacific and Southeast Asia? Here we present an aspirational vision of a future state for Australia’s regional infrastructure partnerships.

Australia partners effectively with Pacific and Southeast Asian countries on infrastructure that is driven by their needs. This helps neighbouring countries realise greater economic growth, human development, security, and stability by supporting them to build and maintain high-quality capability enhancements in critical areas like transport, communications, and energy, as well as social capacities such as justice, health and education.

In doing so, Australia has a clear sense of what its own interests are in meeting the diverse infrastructure needs of the region. It sees regional infrastructure development – and the various means of supporting it – as a complex tool of statecraft that can pursue multiple different interests and objectives in parallel. Australia explicitly recognises and factors in the broad array of imperatives across international policy, including political and strategic calculations, with development objectives as the overriding goal.

For every decision at both the policy or program level, there needs to be greater clarity of what Australia is seeking to achieve with its infrastructure investments and a clear understanding of what a successful outcome looks like. At the same time, there is a recognition that if infrastructure is pursued for reasons of political influence or strategic denial that there will likely be trade-offs in terms of development outcomes – at least in terms of consuming limited resources.

Australia’s infrastructure offering to the region is broad. It seeks to complement and enhance partner countries infrastructure needs by providing well planned, designed and constructed outcomes through strong engagement and consultation within the different contexts, and reflecting the diverse needs of, the Pacific and Southeast Asia. While in some cases Australia is effective by being a leading provider of finance and managing projects (especially in the Pacific), it also recognises that it may have a more focussed role providing capacity-building, contributing to multi-donor initiatives, or helping to crowd in other sources of public and private investment.

While grants and gifts may be preferred to loans and other development finance instruments in the context of small developing countries (especially in the Pacific), Australia creatively uses other financial instruments and technical assistance, such as engineering, capacity development and institutional strengthening, to engage other government and private sector financiers.

Recognising the broader ecosystem for infrastructure in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, Australia is a responsible and proactive partner in seeking to coordinate contributions from multiple actors to meet the region’s needs. While seeking to draw investment from the private sector and likeminded sovereign financiers to boost the total pool of capital, Australia is also cognisant of the risks associated with a lack of coordination between actors – especially for small bureaucracies in developing states. Australia is a leader in not only coordinating its own infrastructure programs, but also in promoting mechanisms for collaboration of efforts between other external actors.

Overall, Australia is regarded as an effective and competitive partner throughout the region for meeting the needs of countries in a flexible way that still privileges high standards.

Australia’s approach to infrastructure upholds high standards of transparency, employs rigorous environmental and social safeguards and is non-discriminatory in developing programs and projects. It has a high degree of respect for local capabilities and as much as possible seeks to empower local leadership. To do this, it ensures that projects, programs or other initiatives transfer relevant skills and technology that contribute to a wider economic uplift. Australia ensures that its infrastructure contributions can be sustainably maintained and are culturally appropriate. Strong connections and relationships with civil society throughout the region also reduce potential political risk and corruption associated with investments.

Throughout the region Australia is regarded as a top-tier partner for infrastructure with high-quality offerings that are tailored to local needs. This is especially the case in the Pacific where it is the dominant actor and has historical partnerships and close bonds of kinship. While lacking the financial capability of some other regional actors, Australia’s strategic interests – across development, diplomacy and defence – are best served by being an effective and highly-trusted contributor that adds value to our regional neighbours’ own infrastructure-related development goals through mutual respect and collaborative partnerships.

Principles for Infrastructure Partnership

The high-level principles set out have been developed to guide how Australia should approach partnering with regional countries on infrastructure. These principles are calibrated to apply at a general level to inform decisions in the context of any one relationship, policy process or proposed investment. They are intended to be applied flexibly, driven by the context of specific partner countries.

Given the lack of consensus between sectors in Australia’s international policy on infrastructure, these principles are unlikely to perfectly cohere. These principles are not an aspirational framework – instead, they are designed to guide the Australian Government from an imperfect, disjointed status quo, and as such must respond to that reality. In this sense, they are a first step towards a more integrated approach.

Many of these principles are already being implemented or utilised in government decision making. Their inclusion here should be understood as an endorsement of this. In other instances, these principles are intended to improve how government approaches infrastructure as part of its international policy.

Philosophy and Approach

Process and Delivery

What principles should Australia apply at the policy level in how it thinks about and approaches infrastructure in the region?

What principles should Australia apply at the implementation level in providing support to meet infrastructure needs?

Philosophy and Approach

What principles should Australia apply at the policy level in how it thinks about and approaches infrastructure in the region?

Process and Delivery

What principles should Australia apply at the implementation level in providing support to meet infrastructure needs?

The primary consideration for Australia’s infrastructure decisions should be meeting the needs of partner countries. In seeking to contribute to the infrastructure needs of the region, Australia’s overriding consideration should be to work closely with and be guided by partner countries in how it can support their development and climate resilience.

Australia should pursue a transparent, non-discriminatory and merit-based process for infrastructure projects and programs. Accountability mechanisms should be built into both the financing and construction processes. Procurement processes should be in plain English and standardised. Whether Australia is viewed as a partner of choice relies in part upon the ethics of its investment processes, as well as its ability to engage quickly and respectfully with partner countries’ needs. The Australian public also needs to be confident about how its money is being spent. Australia needs to be aware of the reputational risk of funding projects that are linked to corruption.

Australia should develop an overarching policy framework for how it thinks about infrastructure as a tool of statecraft and measures success. The framework would consider the various perspectives on infrastructure – development, diplomacy and defence – and provide a clear structure for informing decisions to invest in infrastructure initiatives. Explicitly outlining the policy imperatives driving any one infrastructure investment will also allow measures to be put in place to determine whether Australia’s objectives have been met.

Central to Australia’s infrastructure investments should be the transfer of skills and technology to regional partners. This should include processes that allow local actors to be involved in the entire lifespan of a project from conception and design through to construction and implementation, as well as project review. The construction of infrastructure is often the easy part; what is more complex is the building of local capabilities, ongoing maintenance of infrastructure and the systems of governance and regulation to manage and preserve these investments.

While foreign policy and strategic calculations are inevitable in making decisions about infrastructure investments, development outcomes that enhance partner capabilities and allow local communities to flourish should be the primary motivation for Australia’s infrastructure investment. The prosperity and stability of Australia’s immediate neighbourhood is in its own national interest. Political dividends are most likely to flow from investments that meet real needs and support long-term growth and human development. Australia should ensure that it takes a long-term view of its national interests that looks beyond short-term interests in political influence and that also considers the benefits of supporting partner countries’ growth over the long run.

Australia should respect the capabilities of regional partners and encourage local leadership. Many Southeast Asian and Pacific countries already have strong local capabilities, are aware of what skills they have, and have the desire to lead projects. These countries are looking for Australian support, rather than Australian intervention. Other countries are aware of what they are unable to do and will seek Australia’s expertise and skills when needed.

Part of this is ensuring that local capabilities are fostered as much as possible through infrastructure projects. This includes using local experts, contractors, and consultants as much as possible, as well as providing capacity building to cultivate these capabilities.

When strategic or political motivations drive an infrastructure decision, non-ODA funds should be used as much as possible. Australia could consider formally developing a non-ODA strategic infrastructure fund that can be used for purposes where outcomes beyond economic and social development are the primary drivers. Where ODA is used, it must deliver a development dividend.

Australia should take a lifecycle approach to supporting the region’s infrastructure needs. A strategic business case should include assessment of desired impact, resources and skills, value for money and Australia’s capacities. This should occur at every stage in a project or program from planning, construction, operation through to maintenance of infrastructure. Taking such an approach will help Australia and partner countries ensure infrastructure is fit for purpose over time.

Given limited resources, Australia’s approach to infrastructure should be targeted to where Australia has real advantages and strengths. It should not seek to compete directly with larger investors, but take a smarter approach focused on discerning which contributions can produce the most positive impacts within Australia’s financial constraints.

Australia should continue to develop a wide range of infrastructure offerings appropriate to the diverse needs of the Pacific and Southeast Asia. Both large- and small-scale projects should be considered, a range of financial instruments should be available to maximise Australia’s options to support infrastructure development in Southeast Asian economies where catalysing private investment is more feasible. Australia’s strengths in capacity-building (especially project preparedness) with partner countries should be expanded.

Australia should take a proactive and responsible approach to coordinating with other external actors on infrastructure in the region. China and Japan are the largest infrastructure investors in Southeast Asia, and Australia should support partner countries to maximise the potential and returns from these investments. This could include investments in community engagement, safeguarding, and ensuring productivity gains from infrastructure are realised in partner countries’ economies. Alongside this, Australia should assist with promoting visibility and transparency on respective efforts, harmonising due diligence and compliance requirements and helping boost the coordination capacity of partner governments. Respecting the limited capacity of many regional governments to manage multiple external actors by promoting greater coordination will make Australia a more effective and desirable partner.

Australia should prioritise infrastructure financing in the manner that is preferred by each Pacific and other small developing economy. Debt-based finance should be managed as much as possible for these economies (especially in countries with high debt-to-GDP ratios). Reducing, or at least not worsening, debt burdens in a region with major climate risks should be considered a priority. Positively contributing to debt sustainability must be a feature of Australia’s infrastructure offering.

Australia should prioritise internal coordination of its various actors in meeting partner countries’ infrastructure needs. In instances where multiple different parts of government are engaging counterparts in the region on infrastructure, Australia must ensure that parallel contributions are complementary. Different projects and programs should be broadly aligned in terms of priorities and not compete with each other for limited labour and bandwidth from host governments. Australian officials should also look for opportunities to coordinate resources between projects in partner countries.

Australia should ensure the competitiveness of its offers by avoiding unnecessary red tape, while still maintaining high standards. Australia should streamline its processes as much as possible to remove unnecessary hurdles for regional partners – but do so in a way that upholds critical safeguards and standards.

Australia should foster strong relationships with civil society in partner countries to mitigate political and corruption risks with major infrastructure investments. Insight from local actors will help Australia understand local political dynamics and the actual needs of partner countries.

Australia should look to encourage investment from other OECD countries, the EU, multilateral development banks, and the private sector as much as possible. Beyond making its own contributions to regional infrastructure, Australia should be actively encouraging and, where possible, helping facilitate greater infrastructure investment from other actors that is in line with Australia’s interests. Australia should continue to pursue initiatives flagged in the Development Finance Review to crowd in private investment and provide project preparation support.

Any projects, programs or other initiatives Australia contributes to must uphold safeguards. Some relevant principles for Australia include responsible lending, safeguards for the environment, children, vulnerable and disadvantaged groups, displacement and resettlement, Indigenous people, workplace health and safety, local content, climate resilience, equality and inclusion, transparency and high-quality.

Australia should adopt a broader conception of infrastructure that includes ‘social infrastructure’. This includes investing in strengthening social protections and safety nets to buttress economic shocks or the effects of climate change. Social infrastructure can also support prosperity, personal safety and enable democratic processes.

Australia should prioritise supporting infrastructure that is climate resilient, can be sustainably maintained and that is culturally appropriate. While Australia should aspire to developing high-quality infrastructure in the region, this needs to be balanced against what can be affordably and easily maintained by local authorities. Moreover, Australia needs to be cognisant of how infrastructure it contributes sits within the context of partner countries. Facilities or services that generate conspicuous inequality of access can have negative social effects.

Contributors

Thank you to those who have contributed their thoughts during the development of this paper. Views expressed cannot be attributed to any individuals or organisations involved in the process.

Alison McKechnie

Johnstaff International Development

Amrita Malhi

Save the Children

Anna Griffin

Transparency International Australia

Anthea Mulakala

The Asia Foundation

Brad Bowman

SMEC

Caitlin McCaffrie

Centre for Policy Development

Fiona Tarpey

Australian Red Cross

Hayley Channer

United States Studies Centre

Richard Moore

Development Intelligence Lab

Sophie Webber

University of Sydney

Further consultations were held with 13 other experts from across the think tank, academic, NGO and private sectors, as well as with Australian Government officials. AP4D also presented a draft version of this paper at the ANU Pacific update in Fiji in June 2023, receiving feedback from ten experts from across the region.

AP4D is grateful to the Australian Council for International Development’s Policy & Advocacy Team for their support, in particular Jessica Mackenzie and Brigid O’Farrell.

Editors

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons license. You can reprint or republish with attribution.

You can cite this paper as: Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue, What does it look like for Australia to be a Partner for Infrastructure with the Pacific and Southeast Asia (Canberra 2023): www.asiapacific4d.com

Photo on this page: ‘New partnership opportunities to support off-grid renewable energy in the Pacific and Timor-Leste’ from the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific, used under Creative Commons.

This paper is the product of ‘Shaping a Shared Future’, a program funded by the Australian Civil-Military Centre.

Supported by: